Foreign Stones

The European sculptors behind England’s church memorials.

Most modern accounts of church monuments for a general readership find space somewhere for Philip Larkin’s ‘An Arundel Tomb’:

Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

The poem duly appears in Nigel Andrew’s exploration of English church monuments. Like Larkin, the author is alert to the nuances of atmosphere and place. More, he has a lively interest in the personalities commemorated, from the ‘well-fed, pugnacious, self-satisfied’ 3rd Baron Rich at Snarford in Lincolnshire to the innocent infant Penelope Boothby, whose marble effigy in Ashbourne church, Derbyshire brought floods of tears from Georgian and Victorian visitors.

Cheerfully digressive, the author is always ready to show us his cards. He declares a romantic allegiance to an ideal of ‘Platonic England’, a phrase quoted from the poet Geoffrey Hill, who in turn was quoting Coleridge. Andrew is happiest when hunting monuments in low-lying inland counties. He also has a particular devotion to the monuments produced over a period no longer than one human lifetime, from the later Elizabethan decades to the Civil War.

The problem for devotees of deep Englishness is that post-Reformation church monuments aren’t actually very English at all. In their quiet country churches, they may seem to have been nurtured in isolation; but they are the products of a society eager in its upper reaches to adopt or imitate fashions from the Continent – and to pay foreign sculptors to do the job.

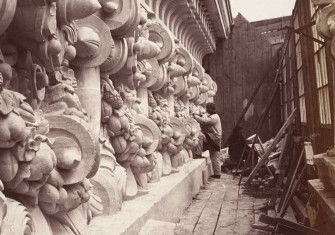

Thus the pace-setting monument-maker of Andrew’s ‘golden age’ were mostly Netherlandish. They gave us the familiar Elizabethan and Jacobean type, in which the recumbent effigy and classical tomb-chest are offset by an architectural backdrop of arches and obelisks. Fresh immigration brought more innovative artists, such as Maximilian Colt. His monument to Lord Salisbury at Hatfield, with its effigy shouldered by four kneeling Virtues, shows Elizabethan formulas in retreat. Even the best English sculptor of the early Stuart period, the appositely named Nicholas Stone, was trained in the Netherlands. Stone carved his figures from imported white marble – another Continental adoption.

Not much changed in the eras that followed, with their sculpted tableaux of posturing, bewigged grandees, at whose expense the author has some harmless fun. If anything, the balance shifted even further away from native talent. The late Stuart favourites Grinling Gibbons, Arnold Quellin and Caius Cibber – a Dutchman, a Fleming and a Dane – were succeeded in Hanoverian times by van Nost, Delvaux, Guelfi, Carpentière, Scheemakers, Rysbrack, Roubiliac, Nollekens ... For the serious monument-hunter it is these names which set the pulse racing. Few of their English rivals come close.

Conversely, when the Civil War drove the foreigners away, the result was 18 years in which, to quote Phoebe Stanton’s classic account, ‘no marked developments occur in English sculpture’. Left to itself, ‘deep England’ proved in creative terms to be a muddy pond. In turn, native-born English sculptors found minimal acclaim or employment beyond these shores until the 18th century was almost over, as Thomas Banks and John Flaxman matched the attainments of the best Neoclassical sculptors abroad. All told, sculpture is the most international of the visual arts practised in these islands in the two and half centuries up to 1800.

Andrew has worked for many years as a journalist and knows how to stimulate and provoke. It’s unlikely that he expects the reader to agree with him on every point. His book is certainly an encouragement to visit and value these monuments more, and to experience their power at first hand. Long may the parish churches of England remain in use, and unlocked, so that others may follow in his trail.

The Mother of Beauty: On the Golden Age of English Church Monuments, and Other Matters of Life and Death

Nigel Andrew

Thorntree Press 244pp £10

Simon Bradley is joint editor of the Pevsner Architectural Guides.