‘Queen James’ by Gareth Russell review

Queen James: The Life and Loves of Britain’s First King by Gareth Russell illuminates the inner life and passions of James VI and I.

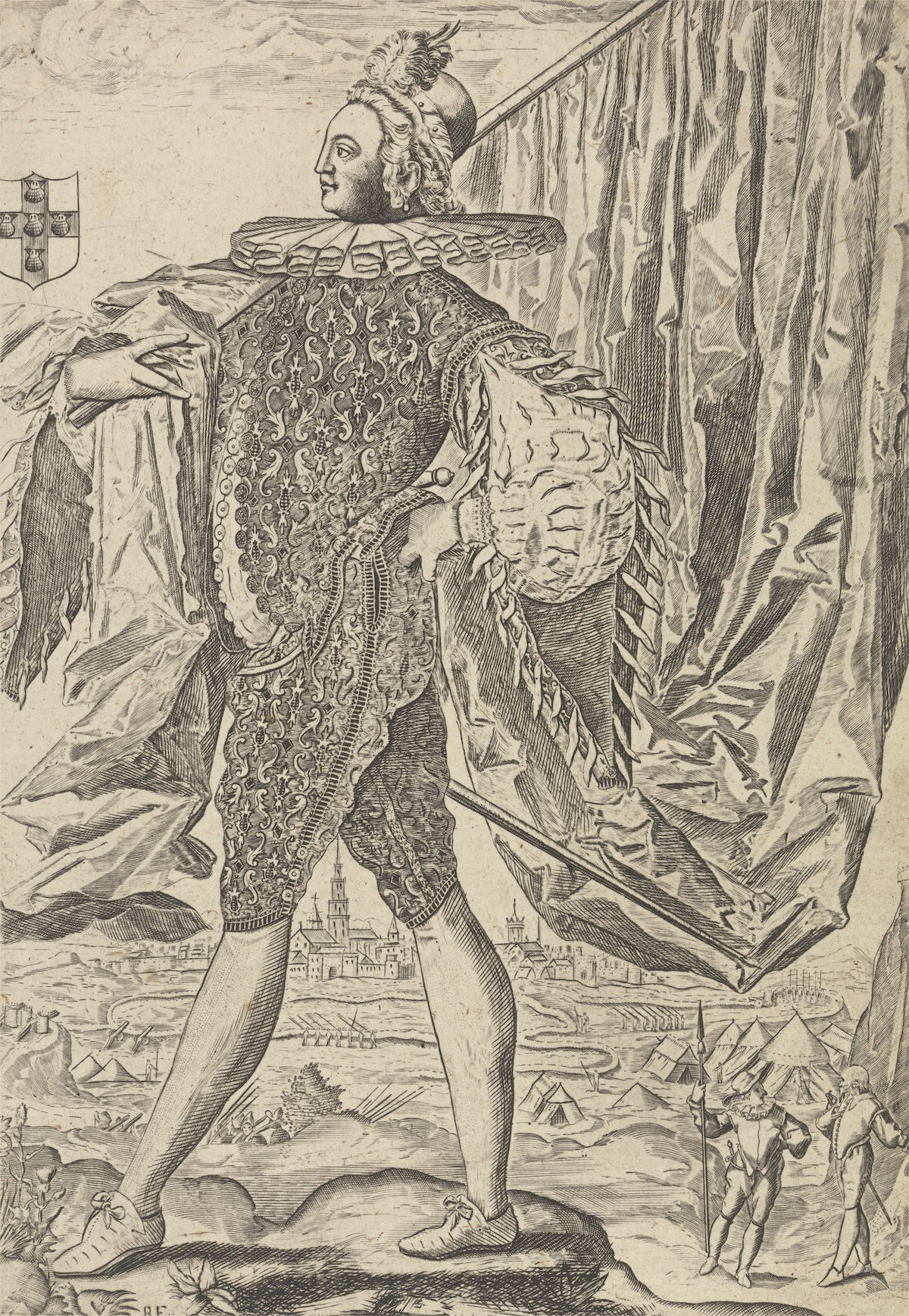

The Scottish throne was a blood-soaked inheritance. James I, crowned at just 11, was murdered in a sewer in 1437. His six-year-old son succeeded as James II and was killed by his own malfunctioning cannon in 1460. Next came James III, aged eight, who died in battle in 1488, leaving the 15-year-old James IV to inherit the crown. He married Margaret Tudor, Henry VIII’s elder sister, only to be killed during the Battle of Flodden in 1513 fighting the English. His 18-month-old son succeeded as James V but succumbed to disease aged 30, leaving a six-day-old baby, Mary, as Queen of Scots. Her life was a tempest of intrigue and tragedy: forced to abdicate in 1567, and executed 20 years later by order of her English cousin, Elizabeth. Mary’s 13-month-old son succeeded as king following her abdication, the sixth James to rule Scotland. Despite the weight of his bloody and scandalous ancestry, a point drilled into him by his abusive tutor George Buchanan, James escaped the brutal fates of his predecessors. He lived to the age of 59 and died not on a battlefield, sewer, or scaffold, but in his own bed, monarch of both Scotland and England: Britain’s first king. His final moments were marked not by violence, but by the heartbroken sobs of his lover, George Villiers – the last in a long line of male favourites.

Gareth Russell’s Queen James masterfully illuminates James and the men he loved. The book emotively explores the king’s relationships, offering a nuanced portrayal of James, the man, in a way that only a biography which does not discriminate against his passion for other men can. Russell’s exploration of James’ personal life distinguishes itself by treating his sexual relationships with sensitivity, challenging the historical tendency to either dismiss, condemn, or ignore his same-sex desire. While some historians have previously claimed that the sexual element to James’ relationships with men is irrelevant, Russell’s biography demonstrates the opposite. The king had passionate bonds with men including Patrick Gray, Alexander (Sandy) Lindsay, Robert Carr, and George Villiers. He argued with these men, kissed them publicly, wept when separated from them, and wrote them passionate letters. These letters, as Russell compellingly argues, only make sense when read as expressions of romantic and erotic love. Villiers’ suggestive longing to have the king’s ‘legs soon in my arms’ and James’ own fear that his desire for Villiers might consume him will resonate with any reader who has experienced love. The king could not bear to be separated from his ‘sweetheart’ and ‘sweet wife’.

Russell skilfully exposes the double standards applied to historical accounts of sexuality. Historians have readily accepted evidence of heterosexual royal affairs, often based on scant documentation, while demanding an impossibly high burden of proof for same-sex relationships. Mary Boleyn’s alleged affair with Henry VIII is widely accepted despite being based on limited evidence – just a few sentences written by a Catholic prior, and an MP. The same is true for dozens of other alleged royal affairs. This contradiction is compounded by the fact that many historical same-sex relationships, out of necessity, sought to obfuscate themselves from the record. As Russell highlights, James is an exception. As king, his life was never at risk because of his sexuality in the way it was for everyday men, such as John Lister and John Shaw, two blacksmiths who were burned in Edinburgh in 1570. James’ position had the paradoxical effect of insulating him from these dangers while exposing him to others.

James’ same-sex affairs were often accompanied by public scandal and ridicule, vividly recounted by Russell through events such as the Gowrie Conspiracy and Overbury Affair. The former possibly saw Alexander Ruthven and James retreat to Gowrie House to have sex, but ended in Ruthven’s death (and almost the king’s) in 1600; the latter saw the king pardon his erstwhile favourite, Robert Carr, an action that seems shocking when compared to the readiness of his Tudor predecessors to execute their former favourites. Despite these affairs, reactions to James’ private life could be tolerant, if begrudgingly so. Nowhere is this exhibited better than the outlook of his wife, the brilliant Anna of Denmark, who emerges as a star of Russell’s narrative, the original ‘dancing queen’. Russell captures Anna’s astuteness and readiness to play the game of courtly intrigue. She was fully aware of James’ intimacy with Carr and even promoted Villiers as his replacement – Villiers was her ‘pet dog’, a nickname the queen used to remind him that without her, he would not have risen to the degree that he did.

Queen James is more than just a biography; it is a reclamation. Gareth Russell masterfully pieces together the fragmented historical record, offering a nuanced and compassionate portrait of James VI and I, a king whose passions and complexities have often been simplified or ignored. By giving voice to the full spectrum of his life and loves, Russell not only illuminates James’ humanity but also challenges us to reconsider the double standards applied to historical accounts of sexuality. James himself once said that sodomy was ‘a sin which ye are bound in conscience never to forgive’. Yet, in stark contradiction, in 1622 he intervened through the Lord High Justice to spare the life of a young servant from the death penalty after he was accused of sodomy, an overreach of his royal prerogative. These contradictions capture the historical multiplicity and intricacy of attitudes towards same-sex love, complexities that shaped James’ own conflicted outlook. This book is a vital contribution to our understanding of James, his kingship, and the complex tapestry of love and power in early modern Britain.

Can we accept that James, Britain’s first and arguably one of its most successful monarchs, was also a lover of men? Russell’s book doesn’t just show us that we can accept this truth about James – it compels us to understand it as essential to his life, reign, and legacy.

-

Queen James: The Life and Loves of Britain’s First King

Gareth Russell

William Collins, 496pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Jack Beesley is a PhD researcher at Manchester Metropolitan University.