How Have Cults Shaped American History?

From a cult’s rogue personalities to its foundational ideologies, how have fringe beliefs guided the direction of the American dream?

‘The idea of the cult represents the very core of the American Dream’

Susan-Mary Grant is Professor of American History at Newcastle University

In the context of American history vary widely. Describe something as a cult to a modern audience and what will most likely spring to mind is the Manson Family murders (1969), the 900 Jonestown murder-suicides (1978), the Branch Davidian murders and mass suicides (Waco, 1993), or the Heaven’s Gate suicides (1997). These examples are extremes, the dramatic and therefore visible tip of an iceberg of some 10,000 cults that exist in America. But they have led to the belief that across the nation, at various points in its history, dangerous cults, centred on a charismatic but violent and corrupt leader, are warping souls, controlling bodies, and destroying lives. The modern cult is, as popularly portrayed, about mind control and, in its worst manifestation, murder.

Yet there is more to the idea of the cult than this. Frequently grounded in an apocalyptic ideology, the modern American cult is in many ways a concentration, and a corruption, of the utopian impulses that formed the nation itself. As the Separatists, better known as the Pilgrim Fathers, set out on the Mayflower in 1620 it was with the intention of establishing a separate religious community within which they could practise their faith freely. The Puritans, too, regarded themselves as especially godly, ‘Visible Saints’ who would establish a more ideal Christian community in which the elect alone were predestined for salvation. Their community, in lay preacher John Winthrop’s famous words, would serve as a ‘City on a Hill’. So blessed by the ‘God of Israel’ would the Massachusetts Bay colony be, Winthrop assured them, that it would become ‘a praise and glory’ to the world.

In this respect the secessionist impulses that informed the first European settlements in North America in the 17th century shaped the nature of the nation eventually created there, the emotional drivers at its heart. Such was the nature of utopia as Thomas More first conceived of it in 1516: the inhabitants of his imaginary, ideal world juxtaposed with the privations of those beyond its walls. In the desire to be distinctive, different, and better, the city on a hill, separate from but visible to the people around it, became an ideal to which they might aspire, but also a community from which they were excluded. The idea of the cult, in short, represents the very core of the American Dream.

‘Stories about “cults” fascinated the public’

Joshua Paddison is author of Unholy Sensations: A Story of Sex, Scandal, and California’s First Cult Scare (Oxford University Press, 2025)

Like everything, the term cult has a history. Before 1890 English speakers used the word to refer simply to religious veneration. However, in the early 1890s, American newspapers started using cult to refer to small religious movements outside the Christian mainstream. Cyrus Teed, the leader of a celibate cooperative society in Chicago, and Thomas Lake Harris, spiritualist poet, prophet, and leader of the Fountaingrove colony in California, became the first examples of a new type of villain: the cult leader.

In what would become known as ‘yellow journalism’, newspapers in the early 1890s employed increasingly sensationalistic tactics to attract urban readers. Editors quickly learned that stories about ‘cults’ fascinated the public by offering glimpses into the margins of American religious belief – the Chicago Daily Tribune complained, in 1890, of the ‘kaleidoscopic cults and crazes’ that had arisen during the preceding century. Drawing on traditions of anti-Catholicism, anti-Islam, and anti-Mormonism, cults were demonised as not just strange, but dangerously un-American. By the mid-1890s Protestant ministers had joined journalists in denouncing the threat that cults represented to morality and democracy. Religious movements such as spiritualism, Christian Science, and Theosophy were described as cults. Blending religious and racial intolerance, writers also described ‘Shinto cults’, ‘Buddhist Tibetan cults’, ‘Hindu cults’, and ‘Voodoo cults’ in Asia and the Caribbean. The real and imagined sexual practices of cults attracted attention, marking their members as depraved. With its history of Asian immigration and religious diversity, California became especially associated with cult activity.

The idea of the cult took hold at the turn of the century because it encapsulated fears held by Americans during an era defined by industrialisation and immigration. Cults could exist anywhere, luring ordinary Americans by preying on their desire for spirituality and community. White women were considered especially vulnerable, an expression of anxieties over changing gender roles as women gained political and economic power. Once established, the ‘cult’ label would be applied again and again.

‘History affected cults before cults affected history’

Megan Goodwin is author of Abusing Religion: Literary Persecution, Sex Scandals, and American Minority Religions (Rutgers University Press, 2020)

American history affected cults before cults affected American history – America’s foundation as a white Christian project is at the heart of which groups get called (and treated as) ‘cults’. Radical religious innovation was at the heart of 1960s counterculture, sparking anxieties about shifting demographics and national values. The moral panic known as the American ‘cult scare’ was rooted in fears about immigration and race-mixing.

A popular image of the counterculture is that of young, white people dressed in orange robes chanting ‘Krishna Krishna’, set, perhaps, to the closing stanzas of George Harrison’s ‘My Sweet Lord’ (released in 1970). There have been various lampoons of the Unification Church’s mass weddings (some 2,000 ‘Moonies’ were married at Madison Square Garden in 1982) and the lavish excesses of the Rajneesh movement, whose Indian leader arrived in the US in 1981. Less well known is the Immigration Act of 1965, without which none of these movements might have landed in the US.

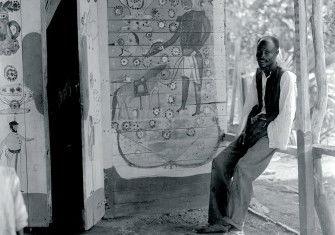

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act repealed quotas set by the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) and the 1924 Immigration Act, both of which had severely curtailed Asian immigration to the US. Passed by Lyndon B. Johnson, the Act facilitated a surge of Asian immigration, and an influx of ‘eastern’ religions such as Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, and Korean Christianity, as well as new movements, such as Hare Krishnas, that were influenced by them. Respectable parents were horrified that their children were embracing ‘cults’ that rejected traditional values. This ‘cult scare’ resulted in multiple high-profile lawsuits against the new movements – in 1989 the George family sued the International Society For Krishna Consciousness Of California, winning an initial $32.5 million (later reduced) – as well as a boom in the ‘deprogramming’ industry (which removed people, often forcibly, from ‘cults’) and a broad dismissal of ‘cult’ members as irrational, coerced, or both. The moral panic culminated in the 1978 Jonestown massacre, widely remembered today as brainwashed mass suicide (and cheap punchline) rather than a devastating example of anti-Black violence – the majority of its victims were Black women – perpetuated against a community hoping to create a fairer world.

‘The Church of Scientology declared war on the federal government’

Edd Graham-Hyde is Associate Lecturer of Humanities at the University of Central Lancashire

Few movements have achieved the notoriety of the Church of Scientology (CoS), a minority religion often denigrated as the archetypal American ‘cult’. Founded in Arizona in 1954, the CoS is a psycho-therapeutic religion (recognised as such in the US since 1993) with a reputation for conspiracy and numerous allegations of abuse.

It is fair to say the CoS has not responded favourably to scrutiny. In 1973 the Guardian’s Office (GO) of the CoS began ‘Operation Snow White’ against the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and other government agencies, with the explicit aim of protecting itself from the federal government, which, it feared, was planning to interfere with its operations. ‘Operation Snow White’ would become one of the biggest embarrassments in US intelligence history. In 1974 the GO successfully planted listening devices in IRS offices, and thereby learned of an imminent audit. By 1975 it had acquired 30,000 pages of IRS documents. It was not until 1977 that the FBI discovered the operation and raided the GO. As the historian Hugh Urban noted in 2011, the FBI found so much material ‘that it took a truck to haul it away’.

In retaliation to the FBI raids, the CoS ‘declared war’ on the federal government with continuous lawsuits and other legal challenges, arguing that it should be afforded the same rights as other religions. This litigation would cost both sides millions. When the IRS recognised the CoS as tax exempt in 1993, David Miscavige, leader of the CoS since 1986, declared that the ‘war is over’.

Whether or not the IRS should be arbitrators of deciding what is, or is not, a religion in US law, Scientology was declared one. The CoS’ conspiratorial thinking and shady operations had, to an extent, been justified. Thus it provided a model for how non-typical religions and conspiracy theory groups could challenge their fringe status with the federal government, ushering in an era in which seemingly harmless alternative beliefs now fuel debates about threats to social security and the freedoms of democracy. When such groups are met with resistance, or facts that contradict their opinion, the example of the CoS shows that perseverance can succeed. We have seen how conspiracy theories and alternative beliefs have transitioned into mainstream US politics.