‘Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain’ review

A history of medieval Iberia that reaches beyond simply a tale of Convivencia and Reconquista.

One reason why history continues to fascinate us, generation after generation, is that there are always new questions to ask, new ways to view the evidence and new lessons to learn. Our medieval forebears felt much the same way: while today we might frame our understanding in different ways, debate over the structure and meaning of past events is nothing new. For centuries, the Iberian Peninsula or, simply, Iberia – that is, modern Spain and Portugal – was a land of three monotheisms, Christianity, Islam and Judaism, multiple ethnicities, at least half a dozen languages and an ever-changing array of kingdoms, emirates and city states, all jostling for power and survival. Not surprisingly, Iberia has never been short of conflicting interpretations of its past, or of chroniclers and poets to fashion narratives that make sense for the times.

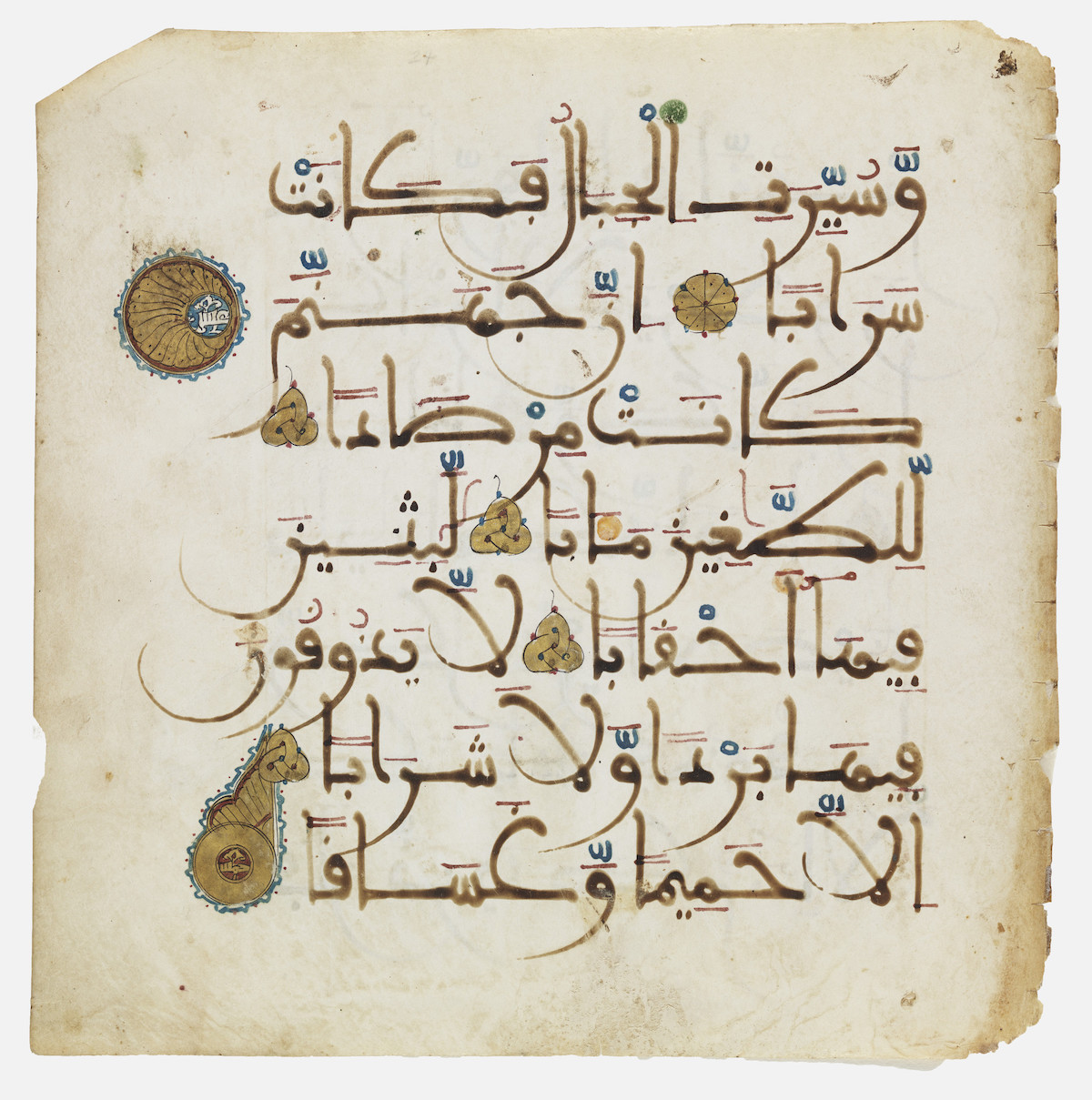

In recent decades, the key debate about medieval Iberia has been multiculturalism. For over 800 years – from the arrival of the Syrian Umayyad dynasty in the early eighth century to the surrender of the last Muslim outpost, Granada, in 1492 – the co-existence of Muslims, Christians and Jews shaped Iberia, in both peace and war. Does its history demonstrate the inevitability of religious conflict, the possibility of multicultural harmony or Convivencia, or something more complicated in between?

With Kingdoms of Faith, given that its author, Brian Catlos, is a professor of religious studies, you might assume his account would play up the ideological divisions of the period. After all, our sources are rich in interreligious (and sometimes racialised) polemic and the stories they tell have an inexorable ring to them: Christian territory ‘reconquered’ from Muslim invaders; a Muslim golden age overwhelmed by the infidel; Jews persecuted whichever way they turn. Yet Catlos resists a reading of Iberian history or, more specifically, Spanish history, that would boil down every conflict – from rivalries between individuals to skirmishes between states – to religion. While he does not completely discount ideology, his focus throughout is on other motives: ambition, greed, opportunism, personality clashes, intellectual curiosity.

Catlos explores case after case of military alliances and cultural exchanges that transcended religious lines. He shows powerful families, such as the Banu Hafsun, switching sides between Christian and Muslim neighbours with whom they were vying for political supremacy, sometimes repeatedly, as well as regimes dependent on the labour, artistic skills or lending power of ‘rival’ faith communities. Catlos argues that ‘theology is simply not an important aspect of most people’s lived religious experience’. Finer points of belief were not visible within, or relevant to, the daily lives of most people, most of the time. Even more obvious markers of difference – language, ethnicity, custom – proved less divisive than might be imagined, for all the efforts of religious (and, sometimes, political) elites to demarcate and strengthen boundaries between communities. Catlos stresses the prevalence of conversion to Islam: Iberian Muslims, while living in a state that was culturally Arabic, were largely North African Berbers or of ‘indigenous’ Iberian (sometimes termed Hispano-Roman) heritage. Their Christian and Jewish neighbours, moreover, became increasingly Arabicised themselves.

Catlos has produced a substantial new synthesis, drawing on the latest Spanish-language scholarship and going into considerably more detail – particularly when it comes to the political history that is Catlos’ primary focus – than previous works, such as Richard Fletcher’s 1992 study, Moorish Spain. For those new to the period, the profusion of names may be confusing at first, but the narrative moves with a pace that belies the book’s size and Catlos bridges the gap by drawing analogies to more familiar histories and contexts, to give his readers a sense of how things were understood and felt. This occasionally misfires: describing the prevailing culture of the ninth-century Muslim court as ‘chivalry on steroids’ makes a lot of sense, but to call it ‘gangsta’ (‘a testosterone-driven, wine-fuelled culture revolving around bling, bros, and biyatches, of biting freestyle wordplay and conspicuous consumption’) is trying too hard. Overall, though, this is a gripping, colourful and humane account of a period that ought to be better known.

- Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain

Brian A. Catlos

Hurst (UK) and Basic Books (US) 496pp £25.00

Nicola Clarke lectures at Newcastle University and is the author of The Muslim Conquest of Iberia (Routledge, 2011).