The Colony That Vanished

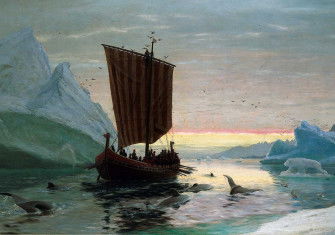

Having prospered for more than 400 years, a medieval colony on Greenland vanished without a trace, but its memory lived on.

The Icelandic sagas tell of Erik the Red, a colourful character who was proclaimed an outlaw from Iceland and sentenced to three years’ banishment. During his exile he reached what we now know as Greenland, around ad 986. When he returned to Iceland, he solicited others to settle there. The late 13th-century Flateyjarbók records that, with a talent for branding, Erik called this new land ‘Greenland’, ‘for he said that might attract men thither, when the land had a fine name’.