Hopes, Fears, and Early Modern Astrology

The concerns of daily life prompted early modern people to seek reassurance in fate, stars, and astrologers.

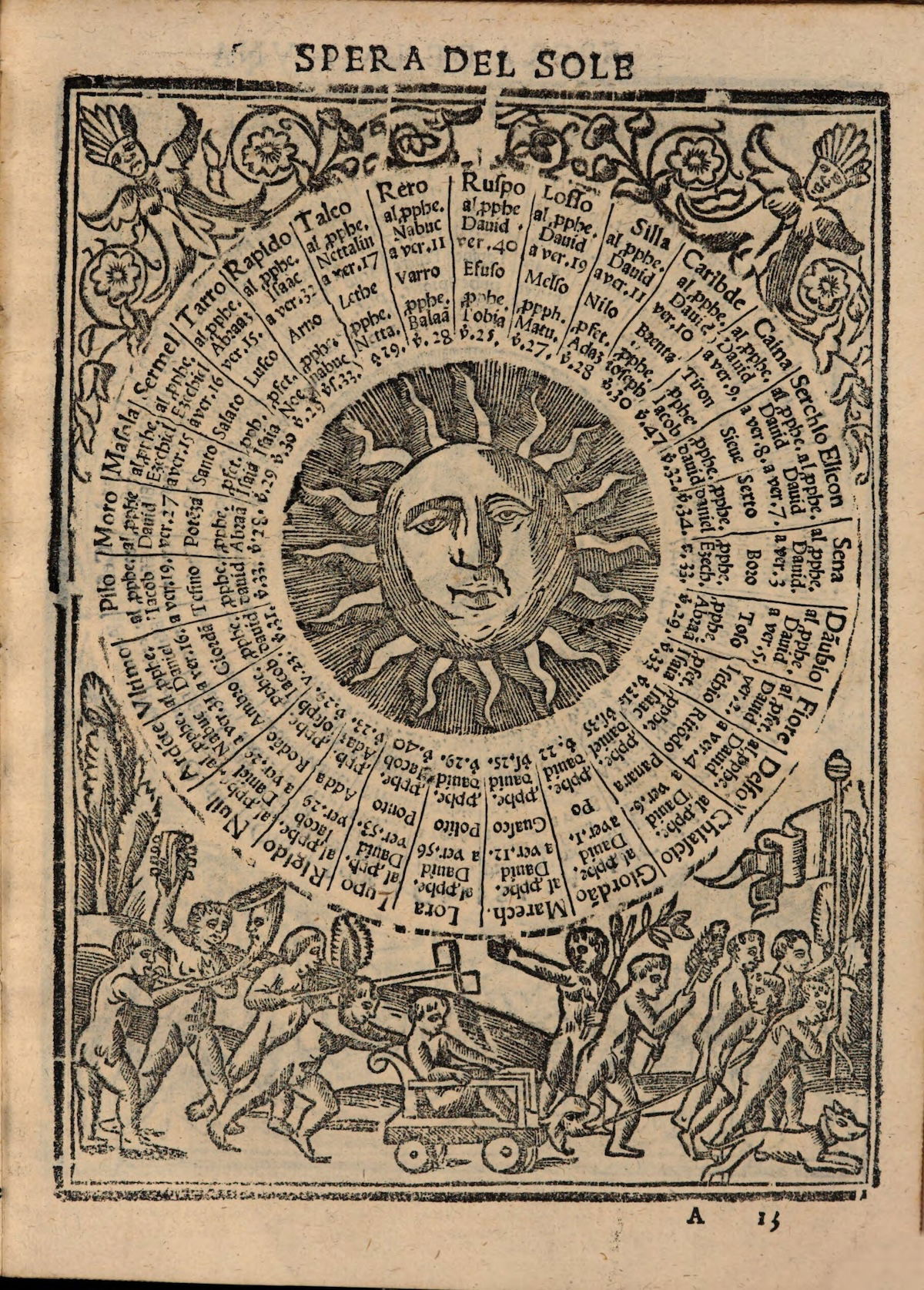

Appearing in 1482, the Libro de la ventura – or Book of Fortune – became a staple of Renaissance parties. A bestseller across Europe, this parlour game was translated into numerous languages, was lavishly illustrated, and survives in many editions. The point of the game was to divine answers to tricky questions, a series of which players could choose from. Will my upcoming trip go smoothly? Will I recover from this illness? Does my spouse truly love me? Once a question was selected, the player rolled three dice then navigated their way through the book, following prompts until they landed on an answer.