Remembering Russia’s Great War

Long overshadowed by the Revolution and the Second World War, there is renewed interest in the earlier, imperialist conflict.

The Eastern Front in the First World War commands far less attention than the Western, even though it extended further, involved more soldiers and probably resulted in more losses. It saw four empires destroyed: Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany and Turkey. Russia lost at least as many men as any other combatant, yet its contribution has often been neglected, no doubt because Russia has often been considered apart from Europe, especially after the Revolution of 1917. The Allies welcomed the fall of the autocratic tsar – ‘Bloody Nicholas’ as he was known – and greeted the arrival of democracy in the shape of the Provisional Government under Alexander Kerensky. But the seizure of power by Lenin and the Bolsheviks caused widespread alarm, as the Soviets withdrew from the Great War and the country became cut off from the rest of Europe in both practice and in thought.

The Eastern Front in the First World War commands far less attention than the Western, even though it extended further, involved more soldiers and probably resulted in more losses. It saw four empires destroyed: Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany and Turkey. Russia lost at least as many men as any other combatant, yet its contribution has often been neglected, no doubt because Russia has often been considered apart from Europe, especially after the Revolution of 1917. The Allies welcomed the fall of the autocratic tsar – ‘Bloody Nicholas’ as he was known – and greeted the arrival of democracy in the shape of the Provisional Government under Alexander Kerensky. But the seizure of power by Lenin and the Bolsheviks caused widespread alarm, as the Soviets withdrew from the Great War and the country became cut off from the rest of Europe in both practice and in thought.

For Lenin and his comrades the Great War had been an imperialist venture and was, therefore, to be forgotten in the new communist dawn. Lenin had urged Russian troops to fraternise with their enemies before he took power. With a new history unfolding, the whole episode of imperialist conflict was to be denounced and then confined to oblivion. There would be no commemoration.

Yet, in recent years, the possibility is opening up of a commemoration more fitting to the military sacrifice. Russian and western historians are collaborating in an ambitious project of about 20 volumes on ‘Russia’s Great War and Revolution’. In the first of them, Vera Tolz writes of a shift from 2010 onwards, which makes the First World War the determining moment for modern Russia, not the Revolution. Tolz and her colleagues are likely to reveal much that is new.

During the conflict, in 1916, the Russian Society of Soldiers Who Fell in the War announced a competition to produce appropriate monuments, but in 1918 Lenin signed a decree for the destruction of statues ‘raised in honour of the tsars and their servants’ in favour of new ones of ‘great people in the sphere of revolutionary and social activity’.

In the Soviet Union itself, somewhat surprisingly, any memory of the Eastern Front was kept alive largely by one of the principal pillars of the establishment, the Red Army, which, during the 1930s, studied the strategy and tactics of the conflict between the Russian and German empires from 1914 to 1918. After the Nazi invasion of 1941, this previous encounter, however imperialist, became a key element in the patriotic propaganda of the armed forces.

Until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, though, memories of Russia’s role in the conflict could be found mostly abroad. Already during the Great War, memorials of various kinds, some modest, some more elaborate, were erected in East Prussia and cared for by local people. In Warsaw, Prague and Belgrade, even in an Orthodox cemetery in Berlin, the sacrifices of Russian soldiers were recorded in stone. In France, where detachments of the tsarist army fought, Russian sections were set up in the cemeteries at Soissons, Verdun and elsewhere. In the US, after much wrangling between the Veterans Society and the Orthodox Church, a monument was dedicated at Seattle in 1936 to ‘the memory of 1,700,000 soldiers of the Czar who died during the World War’. Services were often held on Armistice Day, with US veterans in attendance. Such gestures did not encourage the preservation of memory back in the Soviet Union.

Following the demise of the Soviet Union, the situation began to change. After a considerable amount of grassroots activity, including the erection of crosses on the site of the former Moscow City Cemetery by supporters of tsarism among others, it was reopened in 2004 as a ‘Memorial Park Complex for the Heroes of World War One’. The deputy mayor observed that through this restoration ‘we solve historical, political and social problems’. With a change in government policy already apparent from 2010, President Putin approved a law in 2012 that added August 1st, the day of Russia’s entry into the conflict, to the official list of military holidays. Then, in 2013, he announced a competition for the design of a memorial, as well as other tributes to those who died for the Fatherland in the Great War. Duly, on August 1st, 2014, he inaugurated a monument to heroes unjustly forgotten during what journalists called the reign of the ‘wise and great tsar’ Nicholas II, asserting that he was the last leader to come to power legally before Putin.

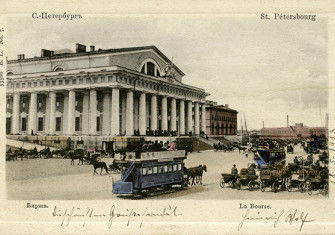

Near St Petersburg, at the palace of Tsarskoe Selo, Nicholas II intended to create a pantheon of patriotic heroes. When hostilities began it became necessary to open a hospital there instead. Now, it is the site of a museum that features some 2,000 items in an exhibition entitled ‘Russia in the Great War’, including documents, weapons, medals and uniforms as well as an old Ford car used by members of the general staff. Video displays follow the arrival and course of the war, from telegrams exchanged by Nicholas and Kaiser Wilhelm to footage of the Eastern Front. One of the aims of the museum is to destroy what is seen as the myth of Russian backwardness: Sergei Naryshkin, chairman of the Russian Historical Society, claims that, at the outbreak of hostilities, Russian development was faster than anywhere else on earth and could have led to world leadership by the mid-20th century.

This revival of interest in Russia’s role in the Great War has arisen not only because of the anniversary but also from Putin’s desire to foster Russian patriotism. Naryshkin dutifully observed: ‘In 1914 Russia, true to its alliance commitments, defended Serbia; now fraternal Ukraine needs our help.’ Having given their lives in the Great War that followed, the fallen were now being asked to make a contribution to resolving the difficulties of more recent times.

Paul Dukes is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Aberdeen.