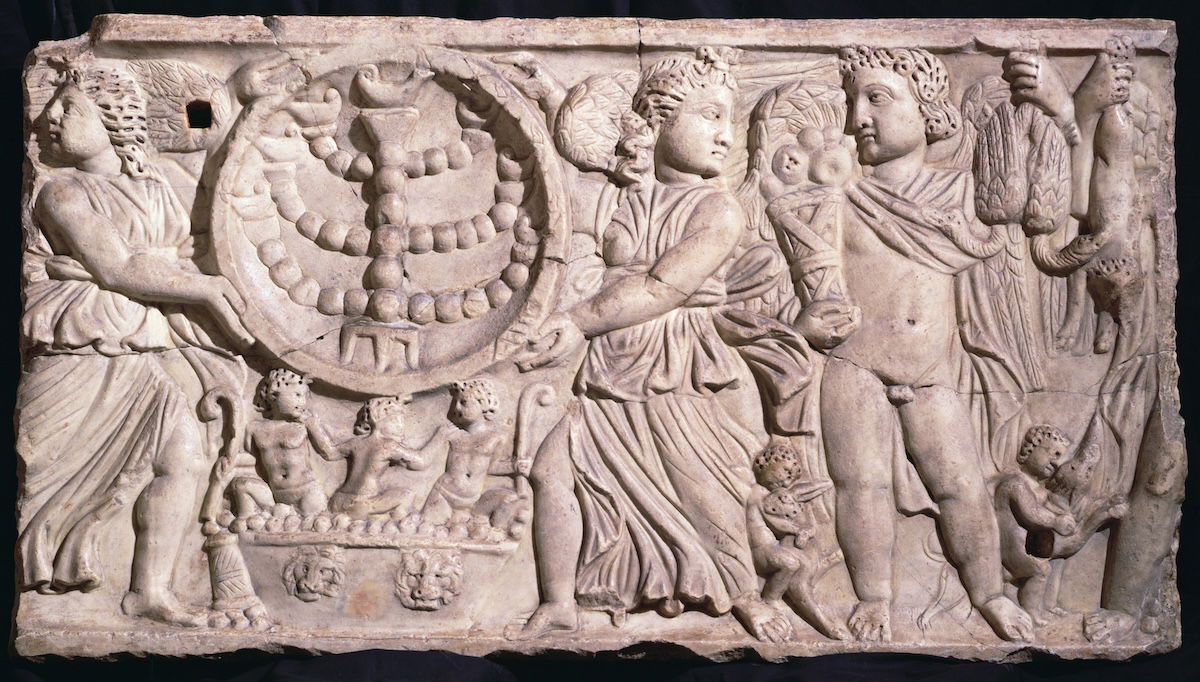

How the Roman Empire Lost its Gods

The Roman Empire had two main populations: gods and humans. By its end, there was only one god left. How, and why, did he reign supreme?

Many gods – Greek, Syrian, Phoenician, Egyptian, Etruscan – lived within the wide borders of the Roman Empire. All ancient peoples – pagans, Jews, and, eventually, Christians – knew this to be the case. Gods attached both to places – a grove, a grotto, a mountain, a temple – and to peoples. Heracles was the progenitor of the Spartans; Jews conceptualised their god as ‘father’. The huge number of deities in the ancient Roman world can be measured by its numberless holy sites and by the various ethnic groups worshipping in them. All gods existed in antiquity, and any god was more powerful than any human. For this reason, a practical religious pluralism long prevailed. Yet as the Empire aged from the first to the fifth centuries, one god emerged supreme. Why did this happen?