1933: The Death of German Democracy

On 1 January 1933, Germany was a democracy with a range of political parties. By the end of the year its parliament was a rubber stamp for Adolf Hitler’s will.

German newspapers offered gloomy predictions for Adolf Hitler’s political prospects. The Social Democratic newspaper Vorwärts ran an article on 1 January 1933 with the headline: ‘Hitler’s Rise and Fall’, suggesting Nazi electoral popularity had peaked at the July 1932 national poll. The Berliner Tageblatt noted: ‘Everywhere in the world people were talking about – what was his name: Adalbert Hitler. Later? He’s vanished!’

Germany was in the middle of a political crisis. During 1932 there had been three chancellors: Heinrich Brüning, Franz von Papen and General Kurt von Schleicher. Each failed to establish a government with a majority in the Reichstag. They were appointed by the 85-year old president Paul von Hindenburg, using arbitrary powers granted to him under Article 48 of the Weimar constitution. He wanted to establish a stable and popular right-wing authoritarian government, which excluded left-wing parties, but was reluctant to appoint Hitler as his chancellor.

Papen felt aggrieved about Schleicher’s role in bringing down his own government and wanted to return to power. He realised he needed the cooperation of Hitler to do so. Political circumstances brought this odd couple together. Hitler and von Papen met a number of times in January to discuss the creation of a coalition government.

The pivotal day was 22 January, when a meeting took place at the palatial home of the rising Nazi politician and wine merchant Joachim von Ribbentrop. Also present was Hindenburg’s son, Oskar, and Otto Meissner, his state secretary. Oskar, who was close to his father, had shown little sympathy for Hitler and National Socialism.

Hitler said he would not join Schleicher’s cabinet, but would accept a place in the coalition if made chancellor. He held a private discussion with Oskar in an adjacent room, where Hitler told him that he alone could save Germany from civil war and crush the communist threat. ‘In the taxi on the way back’, Meissner recalled, ‘Oskar von Hindenburg was very silent; the only remark he made was that there was no help for it, the Nazis had to be taken into the government. My impression was that Hitler had succeeded in getting him under his spell.’

On 23 January, Schleicher met Hindenburg and told him the only alternative to a Hitler-led government was now a ‘military dictatorship’. Hindenburg rejected such an idea. On 28 January, Schleicher resigned as chancellor. Hindenburg summoned von Papen and asked him to take the post, but von Papen replied that Hitler was now the only logical choice and added a confident assertion: ‘Don’t worry, we’ve hired him.’ As Otto Meissner put it: ‘Papen finally won him over to Hitler with the argument that the representatives of the other right-wing parties, which would belong to the government, would restrict Hitler’s freedom of action.’

Hitler appointed

At 11.30am on 30 January, Hitler became chancellor of ‘A Government of National Concentration’. Only two other Nazis were in its cabinet. Hitler gave an impromptu speech, vowing to uphold the Weimar constitution. He awaited a response, but all Hindenburg said was: ‘And now gentlemen, forward with God.’ Hitler went to the Hotel Kaiserhof for lunch. ‘We all had tears in our eyes’, Goebbels noted in his diary. ‘We shook Hitler’s hand. He deserved this. Enormous celebrations.’

The reaction to Hitler coming to power was muted. The Sunday Times commented: ‘Have President von Hindenburg and his comrade Herr von Papen got Hitler into a cage before they wring his neck or are they in a cage?’ The Frankfurter Zeitung noted: ‘The make-up of the cabinet shows that Herr Hitler had to accept significant restrictions.’ The New York Times thought Hitler had ‘no scope for the gratification of his dictatorial ambitions’.

Reichstag Fire

Hitler’s first act as chancellor was to call a general election, hoping to gain enough votes to pass an Enabling Act, which would legally dispense with the Reichstag. The key election slogan was ‘Build with Hitler’. During the campaign, Hitler flew on a speaking tour to 17 cities.

An event that proved hugely advantageous to Hitler’s plans was the Reichstag Fire, which began on the evening of 27 February. The person charged with the crime was Marinus van der Lubbe, an unemployed working-class Dutch communist. On 18 February, van der Lubbe arrived in Berlin after walking all the way from the Netherlands and was seen in a shop on Müller Strasse buying four boxes of firelighters. He started his haphazard arson campaign at three other government buildings in the German capital on 25 February: the welfare office in the Labour Ministry building, Schönenberg Town Hall and the Imperial Palace. He evaded arrest each time. His fourth target was the Reichstag building.

Security there was lax. Van der Lubbe climbed a wall, broke a window and was soon on the first floor. A theology student heard breaking glass as he walked past and noted the time: 9.30pm. Seeing a person with a burning object in his hand through the window he ran to alert a policeman. Van der Lubbe, stripped to the waist, dripping with sweat, was arrested soon after.

Most of Hitler’s political opponents, foreign journalists and many historians believed the Nazis were behind the fire: a pretext to justify the end of democratic government. The finger of suspicion pointed at the Nazi President of the Reichstag, Hermann Göring; an underground passage connected his official residence to the Reichstag. He certainly had the motive, means and opportunity, but conclusive proof has not been found. In Mondorf internment camp near Luxembourg, in the summer of 1945, Göring confided to Schwerin von Krosigk, a former German Finance Minister: ‘I would have been proud to have set the Reichstag on fire, but I was innocent of that crime.’ Van der Lubbe’s story, that he acted alone, remains the most plausible conclusion.

The Reichstag Fire gave Hitler the opportunity to crush both the Communists and the socialist Left. A day after the fire the cabinet agreed to introduce the Decree of the Reich President for the Protection of People and State, known as the Reichstag Fire Decree. It suspended most of the civil rights granted under the Weimar constitution, including free speech, a free press, the right to assemble, imprisonment without trial and the secrecy of telephone calls and post. The Reich Minister of the Interior was granted the power to seize control of any state government unable to keep order. The decree provided the fundamental quasi-legal basis for the abolition of the Weimar state and its swift transformation into a dictatorship.

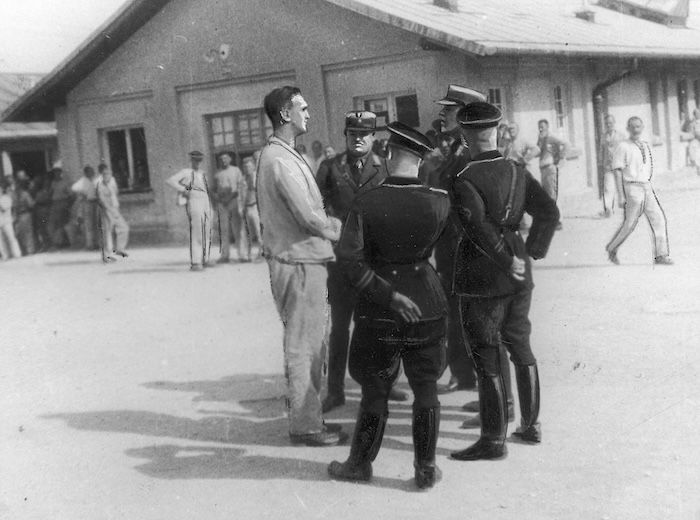

Violence against the Left escalated dramatically. On 3 March, Ernst Thälmann, the Communist Party (KPD) leader, was arrested. He spent the next 11 years in solitary confinement, before his execution on 18 August 1944, on Hitler’s order, in Buchenwald concentration camp. During 1933, over 100,000 political prisoners were detained in what were called ‘wild’ concentration camps located in the larger cities. The Stormtroopers (Sturmabteilung, SA), led by Ernst Röhm, ran more than 240 such camps in Berlin alone during the early months of Nazi rule. Conditions were brutal. It is hard to establish how many people were killed during this orgy of violence; perhaps between 500 and 1,000. It was six months before these ‘wild’ concentration camps were closed.

Last democratic election

In the election of 5 March 1933, the Nazi Party secured 43.9 per cent of the votes, up 10.8 per cent from November 1932. In most histories of the Third Reich, the term ‘only 43.9 per cent voted Nazi’ is frequently mentioned to describe the Nazi electoral performance. Yet in the context of German national elections since 1918 it was an exceptional result. The Nazi Party recorded the highest vote by any German political party in any democratic election from 1919 to 1932. It was 6.7 per cent more than the result gained by the Nazi Party in July 1932; its 17.2 million votes were way ahead of the 13.7 million achieved by the Nazi Party in the 1932 election, the second highest number of votes. This huge increase came almost entirely from voters who had not voted in the previous election. They seemed quite happy to sanction the end of democracy.

In the days following the election, Nazi activists seized power in all the German federal states. Before 5 March, only Prussia, Hamburg, Hesse and Württemberg had Nazi-dominated local governments. Afterwards, the states of Bremen, Lübeck, Shaumberg-Lippe, Hessen, Baden and Saxony all went Nazi in quick succession. The Nazis no longer had to wait for conservative nationalists to invite them into office. This ‘revolution from below’ was led by the SA. The sequence of events in each region followed a familiar pattern: public buildings were occupied; local Nazi leaders demanded control of the police; then the SA occupied government offices. The Reich Interior Minister, Wilhelm Frick, would then invoke emergency measures, appointing Reich commissioners to take charge. These were usually local Nazi Gauleiters. Civil servants and the police were powerless to stop it.

Cultural revolution

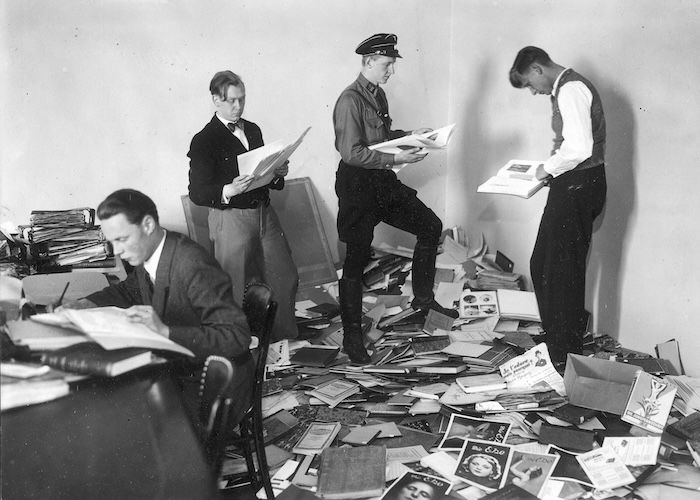

Hitler appointed Joseph Goebbels as the Minister for the People’s Enlightenment and Propaganda on 13 March. His aim was not merely to spread Nazi ideas but to bring culture under Nazi direction. He swiftly brought the press, radio, film, theatre, music, the visual arts, literature and all other cultural organisations under Nazi control. The purge of culture was more extensive than in many other areas of German society.

The removal of Jews and the Left from culture were central priorities. As universities were state funded, it proved relatively easy to purge them of Jews and left-leaning academics. By September 1933, 313 professors had been dismissed. There was a clear-out of Jewish classical musicians, while leftist newspapers disappeared quickly, followed by the Catholic press. On 29 March 1933, Goebbels held a reception for newspaper publishers and told them they should act as ‘a piano on which the government can play’.

All figures in the literary world who were deemed ideologically unsuitable were cleared out. Many fled abroad. It has been estimated that 2,500 novelists and playwrights left Germany in 1933 and, of the 12 bestselling authors of the Weimar period, the works of seven were banned. On 10 May, ceremonial book burnings of ‘un-German’ authors took place throughout Germany.

On 14 July, Goebbels created the Reich Film Chamber, which oversaw the coordination of the film industry. It vetted scripts and purged the industry of Jewish and left-wing actors, writers and directors. Some actors and directors left for Hollywood, but the exodus of film stars was not as extensive as is often supposed: of the 75 most popular box office stars in Germany in 1932, only 13 emigrated after Hitler came to power and hardly any for ideological reasons. There was a similar purge in radio broadcasting.

As Hitler despised modern art, the work of artists branded Entartete (‘degenerate’) was removed from art galleries. During 1933, 27 gallery and museum curators were dismissed. The Reich Chamber of Art vetted the work of all artists, sculptors and architects. Artists who were officially sanctioned produced art which tended to portray family scenes in rural settings or physical beauty in the classical style.

End of democracy

Democracy in Germany effectively came to an end on 23 March with the passing of the Enabling Act. ‘The Law for Removing the Distress of People and the Reich’ passed by 441 votes to 94, attaining the required two-thirds majority. All votes against came from the SPD. The votes of the Centre Party were crucial.

The Enabling Act provided the key legal basis for Hitler’s dictatorship. In just one day, he had dispensed with the president’s authority to issue emergency decrees and made himself independent of the Reichstag. The cabinet now had no power to restrain him. There would be no more openly democratic elections either. Initially the Act was limited to four years, but it was extended in 1937 and 1941 and in 1943 Hitler declared it perpetual. The Reichstag became primarily a venue for Hitler’s speeches. Only seven laws were passed by the Reichstag before 1939.

Underpinning Hitler’s rule was terror administered by two organisations set up in 1933. On 26 April, Göring established the Gestapo (Die Geheime Staatspolizei, or ‘Secret State Police’) in Prussia, under the first Gestapo Law. He defined its role in the following way: ‘Its task is to investigate all political activities in the entire state that pose a danger to the state.’ It was an outgrowth of the Prussian Political Police. The detectives of that organisation were state employees who were assigned to work for the Gestapo. Contrary to popular myth, the Gestapo was not an all powerful Orwellian style ‘Thought Police’; it was under-resourced and overstretched and did not have enough staff to spy on everyone. Most Gestapo investigations began with a tip-off from the public. To make up for its shortage of staff the Gestapo targeted its resources against clearly defined opposition groups, most notably communists, religious dissidents, Jews, foreign workers and a loosely defined group of ‘social outsiders’.

The Gestapo was given the power to arrest political dissidents using a ‘Protective Custody’ order. These ‘enemies of the state’ were supposedly being ‘protected’ from the population. Protective custody ran in parallel with the existing criminal justice system.

The destination for a person defined as a danger to the state was the concentration camp (Konzentrationslager, or KL). These were run not by the state, but the Nazi SS (Schutzstaffel, or ‘Protection Squadron’). At a press conference in Munich on 20 March, the SS leader Heinrich Himmler announced the first camp, at Dachau, on the outskirts of Munich. It was opened because Himmler wanted to bring some order to the chaos of the ‘wild’ SA-run camps, where inmates did not serve a specific sentence and could be held for days, weeks, even years. Those deemed ‘re-educated’ or ‘no longer a danger to the National Community’ were released.

Jewish persecution

Antisemitism was rife among the rank and file of the Nazi Party. It was clear that under Hitler’s rule, Jews were going to suffer severe persecution. In the first week after Hitler came to power, Nazi stormtroopers, taking the law into their own hands, attacked synagogues and beat up Jews. In the last days of March, a fresh wave of anti-Jewish demonstrations occurred. Jewish shops had their windows smashed and Orthodox Jews were singled out for public humiliation and beatings. It has been estimated that, by the end of June 1933, 43 Jews had been murdered by stormtroopers.

In the first openly antisemitic act of Hitler’s new government, a one-day boycott of Jewish shops and businesses, took place on 1 April 1933. Many Jewish shop-owners avoided trouble by closing for the day, though some First World War veterans opened their shops and wore their medals. Sir Horace Rumbold, the British ambassador, concluded the boycott had not been popular with public. Hitler realised that high-profile economic attacks on Jews, while Germany was still in a weak international position, only encouraged negative publicity abroad.

A less openly confrontational approach was required. This was achieved through orderly acts of government legislation, drafted by non-Nazi civil servants. In this way Hitler’s government was able to gradually erode the legal status of Jews and diminish their position in society without recourse to violence. This process began on 7 April when the Law for the Re-establishment of a Professional Civil Service was passed, allowing the purging of Jews, non-Aryans and political opponents. Jewish civil servants, academics and schoolteachers were fired or forced into early retirement. Paragraph III of the Law stipulated the enforced retirement of all officials of ‘non-Aryan’ descent. This was the first specifically antisemitic law passed since German unification in 1871. Hindenburg intervened in favour of Jewish war veterans: ‘If they were worthy of fighting and bleeding for Germany’, Hindenburg wrote in a letter to Hitler, ‘they must be considered worthy of continuing to serve the Fatherland in their profession.’ Hitler, keen to placate Hindenburg, agreed to exclude from the legislation Jews who joined the civil service since 1914 and any Jew who lost a father or son in the First World War.

End of political parties

The inevitable next stage on Hitler’s road to dictatorship was the destruction of all political parties bar the Nazis. In 13 days, from 22 June to 5 July, all other German political parties, except the Nazi party, vanished. On 6 July, in a speech to Reich governors, Hitler said: ‘The political parties have now been abolished. This is an historical event, the meaning and implication of which has not been completely understood.’ But, he warned: ‘Revolution is not a permanent state, it must not develop into a lasting state. The full spate of revolution must be guided into the secure bed of evolution.’ In a speech in Dresden on 13 July, Franz von Papen, the man who promised to have Hitler squealing in the corner when he came to power, admitted defeat:

Who among us thought it possible that the irresistible force of National Socialism would completely subdue the whole German Reich in four short months. The political parties have been dissolved, the institutions of a parliamentary democracy have been abolished by the stroke of a pen and the Chancellor possesses powers not even accorded to the German Kaisers.

On 14 July 1933, the Law Against the Establishment of Political Parties decreed that the Nazi Party was the only legal political party. Germany was now a one-party state controlled by a single leader.

On 14 October, Hitler took his first major gamble in foreign affairs. In a live radio broadcast, he announced Germany was leaving the League of Nations and withdrawing from the world disarmament negotiations. He pinned the blame for these decisions on the western Allies, particularly France, for refusing to grant Germany equal rights. Hitler needed to leave the League of Nations, in a step by step revision of the Versailles Treaty, to proceed unilaterally in foreign affairs.

Hitler asked the German public to endorse his dramatic move in a national referendum. On 12 November, 43.5 million voters, representing 96.1 per cent of all those registered, turned out to vote. Of these, 95.1 per cent overwhelmingly approved of Hitler’s decisions, with just 4.9 per cent or 2.1 million registering disapproval and some 750,000 recording invalid votes. The list of Nazi Party Reichstag deputies was approved by 92.11 per cent, totalling 39.7 million voters. The turnout was 95.3 per cent. Even in Dachau concentration camp, 2,154 out of 2,242 inmates voted for the Nazi Reichstag list.

By the end of the dramatic year of 1933, Hitler had destroyed German democracy and reduced the Reichstag to a rubber stamp for his desires. There were no longer a free press, elections or imprisonment without trial. Political opponents had been purged from culture, the civil service, the police, education and the arts. The process of removing Jews from key positions in society was already underway. The Gestapo and the concentration camps, the underpinnings of the terror system, were up and running.

End of political parties

Despite all this, Hitler’s power at this point was by no means secure. The president retained the constitutional power to dismiss him if he so wished. Conservatives still dominated the judiciary and the higher echelons of the civil service. The German army retained the power to overthrow him. Within the Nazi Party, Ernst Röhm, the radical leader of SA, now wanted Hitler to move on to a ‘second revolution’, which Nazified the police, the civil service and the army. Writing in the SA monthly journal, Röhm commented: ‘The national uprising has thus far travelled part of the way up the path of German Revolution.’ He promised the SA ‘would not tolerate the German revolution falling asleep’.

In Hitler’s Germany there was no chance of that. As the SA would discover.

Frank McDonough is author of The Hitler Years: Triumph 1933-1939 (Head of Zeus, 2019).