Treacherous Waters

Modern naval intelligence, from the 19th century to the Cold War.

Britain’s intelligence agencies have come in from the cold. Scholars of the secret state have, over the past years, enjoyed several weighty, authoritative works on the secret services and their coordinating machinery in Whitehall. Fascinating though these contributions are, they are illustrative of the trend for the ‘core’ agencies, SIS, MI5 and GCHQ, to dominate the discussion of British intelligence, somewhat obscuring the work conducted by the armed services or under the Ministry of Defence. Naval intelligence has, for the broader public, been both familiar and a little estranged once one looks beyond the more headline-grabbing figures of ‘Blinker’ Hall or the buccaneering pioneers of Room 40. Fortunately, Andrew Boyd’s contribution goes some way to redress the balance. Readers of naval history will have enjoyed his previous work on the Royal Navy and will be relieved – though not surprised – to note that he has brought his characteristic thoroughness to this latest book: it is a substantial work.

Boyd combines a flair for research and writing with the practical insights gained from his time served in the Royal Navy as a submariner. Never shy about entertaining the reader with a good intelligence caper, or pen portrait of a splendidly eccentric spymaster, Boyd also elevates his analysis to far bigger issues. He places the activities of naval intelligence closer to the heart of the development of British intelligence than many might have previously considered. Boyd underlines the role played by the Admiralty and naval intelligence figures in developing and nurturing three profoundly significant trends in British intelligence: prioritising sigint, or signals intelligence (and appreciating the value of free thinkers), effective international cooperation with Commonwealth partners and, of course, the United States, and creating effective intelligence assessment organisations, capable of producing ‘a single, integrated operational picture’. The value of these developments has been illustrated time and again as Britain grapples with evolving military and terrorist threats. But a great strength of this book is how it moves beyond the relatively small and narrow world of intelligence. Spying is not an end in and of itself; intelligence exists to serve a customer.

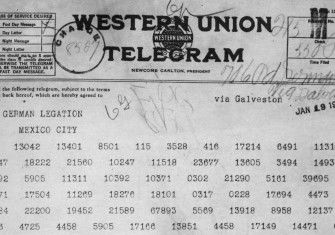

The book spans the foundation of modern naval intelligence in the 19th century, through the Great Wars and on into the Cold War. Readers will encounter familiar figures and cases: Reginald ‘Blinker’ Hall, Jutland, the Zimmerman telegram, the Battle of the Atlantic. Its value, however, is most apparent in the discussion of the broader strategic utility of intelligence. Boyd outlines its value in navigating the treacherous waters of blockade policy during the First World War. When the politics of blockade changed and Britain decided to pursue it more aggressively, because of solid intelligence, effectively collated and assessed, it was able to do so. Similarly, his discussion of the contribution of naval intelligence during the Cold War shines a welcome light on issues that, like their subject matter, have remained mostly hidden from view. Notable here is his chapter on the threat posed by the developing prowess of Soviet submarines in the 1970s. Often, the problem facing intelligence historians is the ‘so what?’ question: how to illustrate the significance of the codebreaking, the liaison, the spies, the assessments and all the rest, to the bigger picture. Boyd meets the challenge with clarity and authority.

British Naval Intelligence Through the Twentieth Century

AndrewBoyd

Seaforth 776pp £35

Huw Dylan is Senior Lecturer in Intelligence Studies and International Security at King’s College, London.