The Shocking Truth

The fluid and unfixed Byzantine Empire.

Writing in the tenth century, the Italian bishop and diplomat Liudprand of Cremona was horrified by the Byzantine imperial court at Constantinople. Liudprand sneered that the Emperor Nikephoros II dressed and acted more like a woman than a man and jeered that he did not deserve to be acclaimed as radiant by his courtiers since his skin was so dark. His idea of Byzantium as the ‘other’, marred by gender and racial prejudice, has cast a long shadow which, even today, sees it all too often excluded from historical writing about medieval Europe.

Roland Betancourt’s book aims to make historians look beyond that shadow. Its title makes use of the term coined in 1989 by the legal theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw to describe how individual aspects of identity, such as race and class, overlap each other and how these aspects must be treated holistically when discussing how people identify themselves and how they are identified by others. Here it refers to the interaction between gender, sexuality and race, how the intersections between these three separate things were understood in Byzantine society and how these understandings endured or shifted across the period of the Empire’s history from (roughly) the fourth century to the 15th. While underpinned by a comparatively modern methodology, and delivered in a prose style that is not totally free of anachronism, the book is rooted in a huge number of meticulously studied late antique and medieval sources. Importantly, Betancourt allows them the freedom to speak for themselves.

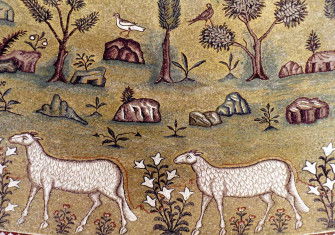

The book is divided into five stand-alone chapters, all of which follow the same structure. Betancourt takes an image or text in which two or more of his categories can be seen, analyses it and uses this analysis as a (very effective) springboard for a discussion of broader aspects of Byzantine society. He begins, for example, with a discussion of the Annunciation and how this was depicted in Byzantine iconography and spoken about by Byzantine homilists. There was a shift in late antiquity from a belief that the Virgin Mary conceived at the moment Gabriel appeared before her, to a belief that she did not conceive until she gave her consent to do so. Betancourt uses this to prompt a discussion of how consent – in both sexual and non-sexual contexts – was understood in Byzantine society. In his second chapter Betancourt examines the depiction of the sixth-century empress Theodora, the wife of Justinian, in Procopius’ Secret History. In contrast to the vast majority of historiography relating to Theodora, which has a tendency to try to refute Procopius’ claims about the empress’ promiscuity, Betancourt asks why it matters whether or not the gossip about Theodora was true. Instead, he asks us to consider what Procopius’ portrayal of Theodora’s gender and sexuality reveals about Byzantine attitudes to (female) sexual freedom beyond the imperial court.

While there is virtually no overlap between them, these first two chapters can be said to have consent as a common theme. He follows this by examining fluidity, focusing on a series of Lives (that is, biographies) written about a group of saints from the late antique and early medieval period who were raised as women but began, in adulthood, to live as men within monastic communities, taking male names and using male pronouns. While previous scholarship has treated these saints merely as women in disguise, Betancourt is clear that they were transgender men and that their Lives reveal communities which accepted and affirmed their identities. This prompts a broader examination of the spectrum of gender identity in Byzantium, offering a particularly interesting discussion on the links in Byzantine thought between masculinity and holiness. Betancourt uses the image of St Thomas touching the wounds of Christ to consider the ways in which monastic communities (in this instance, male) talked about same-gender sexual and non-sexual intimacy and sexual and non-sexual desire.

Betancourt concludes with the story of the unnamed Ethiopian eunuch baptised by St Philip in the eighth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles and, in particular, the representation of this scene in the 11th-century Menologion (a collection of religious readings arranged according to the liturgical calendar). Belonging to the emperor Basil II, the representation is unusual as it actually shows the eunuch as being black, rather than the ambiguously light-skinned portrayal more common in Byzantine art. Betancourt uses this image to discuss the Byzantine connection between skin colour and gender stereotypes, with dark skin praised throughout the Empire’s history as indicative of masculinity and authority. The shock this caused among contemporary western Europeans is palpable in the sources Betancourt quotes (including Liudprand) and he makes a convincing case for the inclusion of Byzantium as standard in scholarship discussing topics such as race and gender in medieval Europe.

However, there are certain facets of identity, which intersect with gender, sexuality and race and which could deepen Betancourt’s analysis of all three, that are missing from this book. Byzantine understandings of class are almost totally absent from the analysis. All of the case studies he chooses relate in some way to the rich and powerful. Betancourt acknowledges this absence and he is certainly not the first premodern historian whose work has been constrained by the need to to rely on elite sources, but several sections of the text have the implication that the powerless would have had broadly similar experiences to the Byzantine elite. It is, however, in keeping with the book’s aims that in emphasising what overlaps we are forced to consider what is missing.

Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender and Race in the Middle Ages

Roland Betancourt

Princeton 288pp £30

Adele Curness is completing a PhD in Byzantine history at St John’s College, University of Oxford.

![‘Scientific Researches! New Discoveries in Pneumaticks! [sic] or an Experimental Lecture on the Powers of Air, May 23, 1802’, by James Gillray. Minneapolis Institute of Art. Public Domain.](/sites/default/files/styles/teaser_list/public/2025-03/lecture_history_today_0.jpg?itok=mHN_obPV)