City and Centre

Ravenna between Constantinople and Charlemagne.

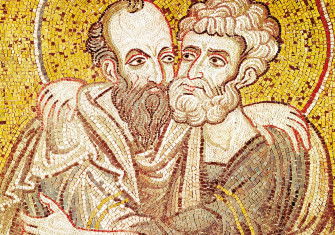

The mosaics of the Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna have featured on the covers of books and have inspired jewellery, perfume, fashion and theatre. Karl Lagerfeld based his 2011 collection for Chanel on Theodora; her very name is enough to evoke mystery, luxury and exoticism. My first sight of Ravenna was in 1963 in the course of a three-week tour by car to Rome and Northern Italy. It was four years after Judith Herrin’s first visit in 1959 and I too was stunned by its glorious mosaics, not only those in San Vitale but also the starry dome in the fifth-century mausoleum of Galla Placidia and the unforgettable row of lambs in the apse of Sant’Apollinare in Classe, consecrated in 549. Repairs to war damage had begun in the 1950s and the town became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996. When I returned in the 1990s its many Late Antique and Byzantine buildings were beautifully presented, with impressive information on the successive remodellings of the churches that took place during its transition from late Roman capital to Ostrogothic and then Byzantine city. As Herrin shows, Ravenna has a story to tell.

With its location on the marshy coast of north-east Italy, Ravenna also has a less well-known treasure: a collection of documents from the chancery of the local archbishopric, written on papyri and dating from the fifth to the eighth century. They allow Herrin to describe something of the lives of the town’s citizens, soldiers, rich women and minor officials, Gothic and Roman, with their property, donations and slaves, their mixture of Greek and Latin and their changing patterns of nomenclature. The presence of the army made Ravennate society an interesting mix of military and civil personnel. And Ravenna had its own historian, the ninth-century Agnellus, who provides a wealth of other information on the town’s changing character. But in Herrin’s words, the city was ‘built on sandbanks and wooden piles’ and it was captured by the Lombards in 751. That was not the end of the story. Ravenna and its archbishops did their best to hold on but fell under the influence of the pope and the future lay not with Constantinople but with Charlemagne. The port and harbour in the lagoon at Classis silted up and it was Ravenna’s northern neighbour Venice that was able to seize the opportunities offered by new trading links across the Adriatic and further east.

In the early fifth century the Roman capital in the west was moved from Milan to Ravenna and it later became the city that Theodoric the Ostrogoth made his capital. Justinian’s general, Belisarius, captured it in 540 and, after the final defeat of the Ostrogoths by the Byzantines in 554, it became the centre of eastern rule in Italy. From the late sixth century it had a Byzantine administration under an official known as the exarch, an arrangement that lasted until the city fell to the Lombards. The exarch was also responsible for other Italian cities, including Rome and Naples. Southern Italy and Sicily also remained under east Roman rule; but by now Italy was fragmented, with the Lombards occupying much of the hinterland. Differences of religion between the Arian Ostrogoths and the Byzantines had compounded the situation in Ravenna, while the Lombards only gradually adopted catholic Christianity. As Herrin demonstrates, Ravenna rather than Rome remained the centre for east Roman rule from Constantinople, but it was now shaped by the changing external situation rather than shaping it.

Some of the changes are apparent in the remodelling of its most famous buildings, especially Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, where the striking mosaics depicting Theodoric’s palace were changed and the image of Theodoric himself removed in the 560s. The octagonal church of San Vitale with its famous depictions of Justinian and Theodora also had a complex history; it had been begun during Theodoric’s reign and was completed in 547 under the archbishop Maximian and with the patronage of a local financier, before the final defeat of the Ostrogoths in Italy. By the end of Justinian’s reign nine Arian churches had been adapted for catholic worship.

Herrin tells the changing story of Ravenna as it unfolds from the end of the fourth century to the ninth in a series of short, accessible sections with the aid of luscious illustrations. Her first book, The Formation of Christendom, covered a similar period on a wider geographical scale; here in contrast she describes how the history of one city, very small by modern standards, took place in the context of a series of profound transformations in Italy and the Mediterranean world. Herrin prefers the term Early Christendom over Late Antiquity, invoking her earlier book. Even if, as she explains so well, Ravenna was itself a Byzantine outpost for two of the centuries covered here, Early Christendom is a term that points forward to the history of western Europe. The Christianity of Byzantine Ravenna was the orthodox Christianity of Constantinople, but a different and powerful Christian force was developing, focused on Rome. Herrin is not herself inclined to sympathise with the immense importance attached by contemporaries to doctrinal and other differences between Christians, but they, too, are an inescapable part of her story.

Recent historians have changed how we think of Ostrogothic Italy and of the religious politics of the wider seventh-century Mediterranean world, including the emergence of Islam and the new and disruptive factor represented by Arab rule. There is more to Ravenna than its mosaics and Judith Herrin concludes her story with the rise of Charlemagne and the turn towards the west. As she explains so persuasively, the changing fortunes of this small city provide a window through which we can glimpse the tectonic shifts that shaped the future of Europe.

Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe

Judith Herrin

Allen Lane 576pp £25

Averil Cameron was Warden of Keble College Oxford and Professor of Late Antique and Byzantine History.