‘The Crisis of Colonial Anglicanism’ by Martyn Percy review

The Crisis of Colonial Anglicanism: Empire, Slavery and Revolt in the Church of England by Martyn Percy takes the British Empire’s church militant to task. Is there a case to answer?

The morning after Edward VII was crowned King of Great Britain and Emperor of India in Westminster Abbey, Canon Welldon treated the colonial troops who had attended the ceremony to a valedictory sermon. An Old Etonian and a former headmaster of Harrow who had until recently been bishop of Calcutta, Welldon was the embodiment of upper-class and imperial purpose. His sermon described the Abbey as belonging ‘not to England only, but to the Empire; not to the Empire only, but to the whole Anglo-Saxon race’. He ordered the troops to tell their friends in the colonies that ‘God has done great things for them already, that He has called them to an imperial destiny, and that they must not and shall not prove unworthy of it’.

Welldon and his empire are long dead, but Martyn Percy is convinced that his assumptions still haunt the Church of England. Percy is a figure familiar from ecclesiastical history: the clerical malcontent. In 2022 he stepped down as Dean of Christ Church, Oxford after acrimonious disputes with its governing body. Soon thereafter, he announced his departure from the Church. Like other rebels in orders, Percy uses a polemical reading of the Church’s history to justify his quarrel with it. The Crisis of Colonial Anglicanism also exploits a vogue in popular history: the exposure of this or that institution’s forgotten links with empire or the slave trade with a view to reforming or discrediting it. Percy thinks it high time for the Church to get the same treatment as the monarchy or the country house. Its authoritarianism is a hangover of empire.

His book fails to set out its allegations very well. Because it is less a systematic history of the Church’s imperial commitments than a set of digressive essays on them, there are many gaps and much repetition. The metaphors are tired (imperialism is the ‘DNA coding’ of the Church), mixed (the Church is ‘hitching a ride’ on empire but is also its ‘spiritual wing’), or failed (clergy are ‘resisting the tsunami’ of episcopal directives – you run away from tidal waves). Windy moralism alternates with insider sniping – at candidates for the deanery of Christ Church, for example. As in many lay sermons, shopworn phrases stand in for a thorough scrutiny of the evidence. Percy often contents himself with noting that the history of this or that enormity (the slave trade, the eugenics movement) should make ‘uncomfortable reading’ for the Church, without explaining why it should be so.

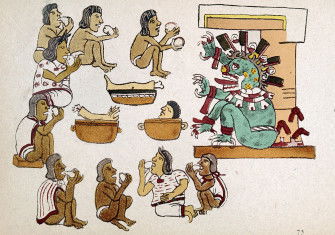

Still, some interlocking claims emerge, which are as plausible as they are provocative. The phrase ‘Anglican Communion’ disguises the ramshackle and discreditable way the Church grew overseas. Chaplains who travelled with regiments, on board naval vessels, or as employees of the East India Company were able to plant churches across the expanding British world. A necessary cost of doing so was their turning a politic blind eye to the crimes of colonists. Often, Church agencies benefitted financially from them. In the 18th century, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospels branded its slaves with the word ‘Society’ to make it easier to capture them if they escaped.

Percy glosses over the fact that this institutional pre-eminence evaporated over the course of the 19th century, as governments across the British world disestablished the Church in the colonies. He has nothing to say about Protestant nonconformists, who often vied with the Church in exploiting colonial openings and in developing an uplifting vision of the White Man’s Burden. Yet he is right to argue that the Church’s imperial ride has generated some intractable problems for the present.

The most serious problem is the coherence of Anglicanism. The consecration of Samuel Seabury as the first American bishop after the War of Independence – by a Scottish bishop – signalled that Anglicanism was already a bigger and more inchoate organism than the Church of England. The Lambeth Conferences, which began in 1867 at the urging of American Episcopalians, were convened but have never been controlled by the archbishops of Canterbury. It has got ever harder for the Conferences to agree a shared line on such vexed questions as homosexuality because the churches who attend them have sharply contrasting theologies and origins. Uruguayan Anglicans, for instance, have inherited the conservative evangelicalism of the English missionaries, while the Brazilian Anglican Church is loyal to the liberalism of its American Episcopalian founders.

Giving a steer to a fissuring global communion while coping with declining congregations at home is a daunting challenge. Percy feels that what he calls the Church’s monarchism makes it worse. It is too close to its supreme governor, the king, whose recent coronation Percy admits to enjoying but criticises for its mystical flourishes and predominantly Anglican character. Worse, bishops and their ‘ecclesiocrats’ act like petty kings, lording it over their clergy and their peers in the developing world. They would do better to emulate the egalitarianism of New World Episcopalianism – though Percy’s faith in the American genius for democracy looks vulnerable today.

Since Brexit, it has been trendy to say that the English are at once nostalgic for, and amnesiac about, empire. But if you are going to argue that the past inflicted a ‘near fatal soul wound’ on the English, then you need to be clear and accurate about it. Percy rarely is. To illustrate the wrongs of missionaries in China, he brings up the sexual abuse committed by a diplomat. He mysteriously writes that missionary ‘epistemicide’ caused ‘famines’. In the rush to draw up the charge sheet, he also misses a persistent streak of Anglican scepticism about empire. Canon Welldon had left Calcutta pessimistic about Christianity’s future in India and disapproving of the clergy’s tendency to act as a mouthpiece for the ‘sultanized’ viceroy, Lord Curzon. It was one thing to have an ‘imperial destiny’, quite another to meet it.

-

The Crisis of Colonial Anglicanism: Empire, Slavery and Revolt in the Church of England

Martyn Percy

Hurst, 352pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Michael Ledger-Lomas is a historian of religion.