‘The Last Dynasty’ and ‘The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome’ review

Can The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra and The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies fashion a finale for the pharaohs?

Like many Egyptologists, the Ptolemies make me rather uncomfortable. It is a cliché to say that the Ptolemaic period (323-30 BC) has been thought of as too Egyptian for most classicists and too Greek for many Egyptologists. Much has been written about the period from both perspectives, but a good quality synthesis has proven elusive.

Many studies have, understandably, focused on the glamorous final star of the Ptolemaic stage, Queen Cleopatra VII (50-30 BC). But given the comparative dominance of Egypt, Greece and Rome in studies of the ancient world, it is surprising that the whole Ptolemaic period has not been subject to more popular interest. Like the proverbial bus, you wait ages for one and two show up at once.

Toby Wilkinson trained as an Egyptologist and is known for his popular treatments of a range of Pharaonic subjects. Here he turns his attention to the last dynasty, proving especially adept at connecting the Ptolemies with Egypt’s ancient traditions. While a more recent convert to Egyptological pursuits, Romanist Guy de la Bédoyère covers the same timespan with similar aplomb. He frames his narrative with the gradual appearance of Rome on the horizon.

Both make extensive use of official texts – often the same ones – but compare and contrast them with a wide range of contemporary documentary accounts (which have survived in profusion) and the words of (usually later and biased) classical authors. This synthesis of sources builds a dynamic picture of the period, something often missing for much of the rest of the ancient world and Egypt in particular.

Although most people know about the ignominious end of the Ptolemies, the ambition of the dynasty’s establishment is breathtaking. Ptolemy I (367-283 BC) emerges in both books as an extremely compelling character, even compared to his childhood friend and predecessor Alexander of Macedon. Having had the audacity to essentially kidnap Alexander’s body in Syria while still only satrap (‘governor’) of Egypt, Ptolemy was responsible for developing Alexandria into the magnificent hub it became, while also maintaining military sense and pursuing an impressive amount of learning. It is probably not too much of a spoiler to say that his successors were not nearly so adept at the business of government.

Because of the nature of the posthumous division of Alexander’s territorial possessions, the family of Ptolemy I was connected to several royal houses in the eastern Mediterranean. This included the Seleucid empire of western Asia. Much wrangling occurred over control of Cyrenaica (on the Libyan coast), parts of Syria and Cyprus. Keeping track of names is rather confusing – which Antiochus hated which Ptolemy is often difficult to fully fathom. Both books carry helpful family trees and timelines.

The internecine and incestuous family relationships among the Ptolemies and their relations make for tough or titillating reading, depending on your perspective. If you can keep up with them, the intrigues, alliances, co-regencies and revolts provide an almost unparalleled insight into ancient palace life. Perhaps most informatively, one can nuance the apparent personal power of individual

royal figures with the significance of court officials – the scheming Sosibius in the court of Ptolemy IV, for example – and one is left wondering just how atypical the intrigues of the Ptolemaic court were, given the dearth of similarly detailed documentation for earlier Pharaonic dynasties.

Amid all the documented squabbling and bloodshed, it is notable just how important a position royal women held. Despite the focus on Cleopatra VII it is clear her foremothers were politically active and highly regarded, sharing the prescribed divinity of their male co-regents and viewed as ‘Female Pharaoh’ and ‘Female Horus’ – designations that eluded even the most powerful regnant queens of the Pharaonic era. How ingrained in the Egyptian ‘character’ this prominence of female power was is hard to say, but it may also have been a result of Macedonian ideas about elite women’s roles. However the situation came about, it certainly confirmed later Roman assessments of the oriental decadence of Egypt under the Ptolemies.

As de la Bédoyère makes clear, the Roman encounter with Egypt predated by well over a century the meeting of Cleopatra and Julius Caesar in 48 BC. It is rightly emphasised that Rome appeared rather suddenly as a superpower after the Punic Wars – and that had the Ptolemies and their neighbouring royal houses not been fighting among each other then they could have been, in confederation, a serious rival to Rome. It may surprise some readers that the relationship was, for a time, a two-way street: Rome begged Egypt for grain while Egypt had to later request Roman help in giving sanctuary to, and assuring the succession of, the Ptolemaic throne. The death of Cleopatra, despite the melodrama, was a critical moment for Egypt, although the realities of a triumph of West over East are not simple; both authors emphasise the legacy of the Ptolemaic period on Egypt under Roman rule – and the irony that Octavian, as Emperor Augustus, indulged in the very self-aggrandisement he claimed to despise when he mocked Egyptian customs.

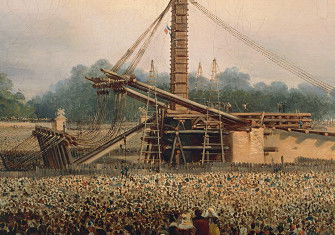

Despite the disaffection of some scholars and the broader public, the Ptolemies loom large in the preserved traces of ‘ancient Egypt’ accessible to tourists. Some of the best-preserved temples – Dendera, Edfu, Esna, Kom Ombo, Philae – are largely of Ptolemaic design. Unlike earlier Pharaonic works, which were added to over millennia, these were the manifestation of a single plan – albeit one that might (as at Edfu) have taken well over a century to realise. Relationships between the Greek-speaking court and the indigenous Egyptian temple are well documented in official pronouncements – the most famous being the Memphis Decree of 196 BC, better known as the text on the Rosetta Stone. Heavy on such textual sources, and in the absence of much of the architecture of ancient Alexandria, de la Bédoyère makes the insightful point that because we lack the mortal remains of the Ptolemies – although Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III were apparently cremated, the expectation must be that most were mummified – this deprives commentators of an added element to reconstruct historical events. If the survival of earlier New Kingdom royal bodies is anything to go by, such a source of evidence would provide but an unhelpful distraction.

Based on this wealth of contemporary documentation, both authors bring to life a sense of the concerns of ordinary people in Egypt in Ptolemaic times. This can seem rather depressing, as the sources make clear the systematic exploitation of Egypt by the Ptolemaic administration: rapacious taxation on practically everything that could be taxed. The agricultural yield – or the potential for it – was one reason, as Wilkinson observes, that the Ptolemies’ Hellenistic rivals looked on Egypt so covetously. Wilkinson and de la Bédoyère both convey a real sense of the uneasy relationship between the Macedonian elite and the Egyptian population. Of the documentation that has survived from an area like the Faiyum, of those that preserve written complaints most are from Egyptians against Greeks.

Both books are framed – as much by publishers’ guidance as by their authors’ beliefs – by a sense of finality. Yet for most ordinary Egyptians, as for most ancient subjects of contested land, the Roman conquest would have had little impact on their daily lives. ‘Ancient Egypt’ never really ‘fell’ – it simply adapted to its circumstances. Undoubtedly, though, the personalities, politics and priorities of the Ptolemaic period made for unique circumstances. Exploring them is a wild ride but one well worth taking, even for those – like me – who haven’t felt comfortable picking up a book like either of these before.

-

The Last Dynasty: Ancient Egypt from Alexander the Great to Cleopatra

Toby Wilkinson

Bloomsbury, 384pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link) -

The Fall of Egypt and the Rise of Rome: A History of the Ptolemies

Guy de la Bédoyère

Yale University Press, 384pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Campbell Price is Curator of Egypt and Sudan at Manchester Museum and Chair of the Egypt Exploration Society.