‘Gypsies: An English History’ by David Cressy review

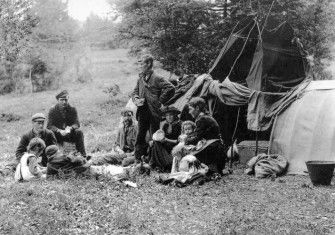

Gypsies: An English History by David Cressy is a sympathetic narrative of a people integral to the national story.

There can be few historical topics that pose more problems than the story of the Gypsies. How do you write a history of people who have tried so assiduously – not without good reason – to avoid the gaze of the state, who have left hardly any written sources of their own and who have been the subject of centuries of fear, prejudice and misunderstanding? It is not even especially easy to say who England’s Gypsies are or were: are they a group with a shared ethnicity, or a literary and social construct? Is the term ‘Gypsy’ a racist one?

This is an elusive, difficult and frustrating topic – a puzzle with many missing pieces. Alas, this book can tell us little about faith, gives only a fleeting glance at demography and tells us much less than we would like about Gypsy culture. Instead, the focus is on Gypsy relations with the wider community: relations founded in the prejudice and fear of that wider world. ‘Perceived as people without roots and without honesty’, Cressy reminds us that the Gypsies were seen as ‘a danger to society, an affront to the state, and offensive to God’. Indeed, between 1563 and 1783 the very fact of being a Gypsy was a hanging offence. The statute was, said a 19th-century commentator, ‘the most barbarous … that ever disgraced our criminal code’. They had a point: although the last hangings were as far back as 1628, this will have been of little comfort to the victims. Indeed, prejudice survived well beyond the anti-Gypsy laws. One correspondent to a local newspaper in the 20th century spoke for many when they dubbed Gypsies ‘shiftless, worthless people … Their morals are not bounded by ordinary rules, and nearly all of them are thieves’.

Cressy is especially good on the early modern period and at puncturing some of the bad history that has attached itself to the subject. He shows an early modernist’s scepticism for the letter of the law: the statutory prohibitions were brutal, but they were hardly ever used. The fanciful ideas – held by some scholars – that Gypsies were some kind of literary construct, or emerged as a response to the alleged transition from feudalism to capitalism, are rejected. Cressy accepts, surely correctly, the evidence that sees the Roma as a group with a history that goes back to ancient India. That said, through the centuries, they came to be bolstered by recruits from the settled population: the poor, the restless, the unsettled, perhaps even those simply wishing to escape the prying Leviathan.

For all the challenges of the subject, Cressy does a good job in telling his story. Yes, it is an outsider’s view, where the Gypsies remain an ‘other’, but he admits this, and there is little else he can do. In fairness, the same could be said about other historical subjects that are far better established: the poor, for example, or criminality. The most engaging section is that which considers in close detail the case of Mary Squires, an 18th-century Gypsy accused of kidnap, found guilty, sentenced to death and then sensationally acquitted. It allows us a vivid glimpse into the world of travelling folk, ebbing and flowing around the English countryside and to and from London.

Cressy is an academic historian, rather than a ‘popular’ one. This is reflected in the style, which is crisp and efficient. He avoids the pitfalls of cliché that beset more sensationalist historical writing. Nonetheless, this is an accessible book, which gives us a sympathetic narrative of a people who are very much part of the English story. For that, it is immensely welcome.

- Gypsies: An English History

David Cressy

Oxford University Press

432pp £25

Jonathan Healey is Associate Professor in Social History at Kellogg College at the University of Oxford.