The Xi’an Incident: The Beginning of the End for Chiang Kai-shek

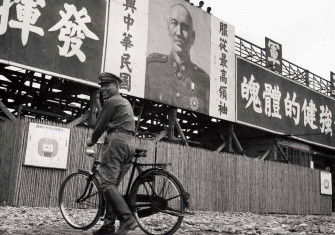

The Xi'an Incident, a tragi-comic sequence of mutiny and kidnapping, marked a crucial stage in the struggle between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists.

The opening shots of the Second World War are sometimes identified as those which ricocheted round the white marble parapets of a Sung Dynasty bridge near Beijing on the night of July 7th, 1937. Diplomatic and journalistic opinion in the West immediately dismissed the exchange (at the fancifully-named Marco Polo Bridge of Lukouchiou) as yet another example of the alarms and excursions which had punctuated the past seven years of deteriorating relations between China and Japan.

Japan's provocation of China had taken tragic and comic turns since the Imperial forces' first act of aggression in Manchuria. Lukouchiou was pure farce. Japanese forces had swept over the Great Wall to within sight of Beijing and they had developed a penchant for showing their strength – depicted in the world's press as shouting banzais to the rising sun.

The demonstration that July night 50 years ago was different, however. A Japanese force of three infantry regiments, supported by tanks, deployed near the bridge on night manoeuvres. From the other side of the span came a challenge from an officer of the Chinese 29th Army; to be answered by gunfire.