The Story of Peru’s Cloud Warriors

What can be known about Peru’s pre-Incan civilisation, the Chachapoya people or ‘Warriors of the Clouds’?

Recent archaeological discoveries have shed new light on the history of Peru’s Chachapoya people. Until the 1990s most of what we knew about this pre-Columbian culture – referred to as the ‘Warriors of the Clouds’ by the Inca – was based on third-hand stories from unreliable Spanish chroniclers. Even today, the Chachapoya jigsaw has more gaps than pieces. Yet interest and knowledge in the erstwhile civilisation is growing. In 2017, the hilltop Chachapoya ruins of Kuélap were equipped with a cable car and marketed by the Peruvian government as a northern rival to Machu Picchu. Two years later Unesco placed the ‘Chachapoyas sites of the Utcubamba Valley’ on its tentative list of World Heritage Sites being considered for nomination.

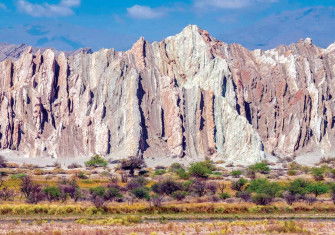

Predating the Inca by over six centuries, Chachapoya culture flourished from around AD 800 in Peru’s remote northern highlands, an area of crinkled mountains, deep canyons and lofty waterfalls where the eastern slopes of the Andes dissolve into the humid Amazon basin. Here a loosely unified society of cacicazgos (small kingdoms) gradually took root, farming terraced fields and acting as trading intermediaries between the Andes and the Amazon. The population, which may have numbered 500,000 at its peak, produced powerful shaman and engendered a tough fighting ethos. It evolved with little outside trauma until the invasion of the Inca in the 1470s.

With no written language, much of what is known about the Chachapoya is derived from archaeological remains found at funerary sites on hard to access limestone cliffs in Peru’s cloud forests. Characterised by sarcophagi with humanoid faces and cottage-like mausoleums that were built into the rockface and adorned with rust-red imagery, these stone tombs or chullpas, which still look down imposingly from isolated hillsides, suggest a vigorous independent culture that was markedly different from its Andean neighbours. In contrast to other South American civilisations, the Chachapoya seemed to eschew hierarchies. Their burial methods, while elaborate, appear to have been relatively egalitarian and the surviving architecture manifests few symbols of status and power.

Complicating investigations, many chullpas have been looted; others, such as those discovered on a cliffside overlooking the Laguna de los Cóndores in 1996, were taken over and reused by the Inca. The Cóndores’ unearthing was a game changer in Peruvian archaeological research, which hinted at the sophistication of the Chachapoya by the time the Inca arrived in the late 15th century. A special museum was built in 2000 in the nearby town of Leimebamba to house the artefacts. Inside the tombs, archaeologists found over 200 Inca-era mummies, along with simple ceramics, silver objects, wood carvings and unique red-hued textiles. The Chachapoya were famed for their weaving; their bright cloths with animalistic motifs were favoured garments of the Inca.

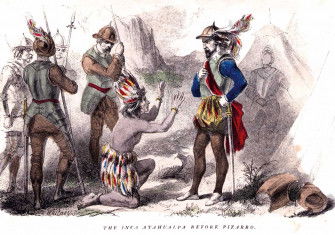

Spanish colonial reports describing the Chachapoya as white-skinned and fair-haired were probably apocryphal, fuelling fantastical tales of their origins about mythical explorers from overseas. Subsequent archaeological research from Laguna de los Cóndores and other sites has dispelled the myth that the Cloud Warriors were displaced Vikings. They were, however, reputed to possess a robust warrior spirit. Refusing to kowtow to the rapidly expanding Inca in the 15th century, they fought ferociously from hilltop forts before their eventual defeat in around 1475. After suing somewhat reluctantly for peace, many of the subjugated people were forcibly relocated to distant parts of the Inca empire to avoid future rebellions. Those who remained sided opportunistically with the Spanish when they arrived in the 1530s, but European diseases and harsh treatment by their new overlords ensured that, by the early 17th century, Chachapoya language and culture had all but disappeared.

The greatest surviving manifestation of Chachapoya civilisation lies in the magnificent ruins of Kuélap, an urban, political and religious site that sits 3,000m above the Utcubamba river valley on a misty mountain ridge defended by 20m-high walls. Kuélap predates the citadel of Machu Picchu by at least 700 years and exhibits stone masonry skills as remarkable as those later displayed by the Inca. However, rather than construct the rectangular dwellings that were common to other South American civilisations, the Chachapoya built circular limestone structures that would have been covered with conical thatched roofs. Equally characteristic are the simple rhomboid friezes and sculpted serpents that decorate stone facades, symbols replicated in at least half a dozen other ruins in the area.

Occupied as early as AD 500, Kuélap was the culmination of a collective effort by cooperating groups of people that lasted centuries. It provides unequivocal evidence of a highly developed, well-organised society existing in northern Peru long before the emergence of the Inca. The massive external walls contain human remains and were probably used as ritual burial sites. Inside the formidable defences, a further 420 buildings have been identified and mapped – from family dwellings to an inverted cylindrical structure thought to be the complex’s ceremonial centre.

Kuélap was abandoned in the late 1500s, possibly after a massacre and a fire. It was rediscovered by a Peruvian judge in 1843 but, due to its remoteness and the touristic fame of Machu Picchu, it was not seriously excavated until the late 1990s. Ongoing digs at the site continue to throw up as many queries as conclusions. While the monumentalism is impressive, questions about the citadel’s day-to-day function, its spiritual status and its significance in wider Chachapoya culture continue to perplex.

Other Chachapoya sites in the area are equally cloaked in mystery. The ruins of Gran Pajatén, 300km south of Kuélap, were stumbled upon by local villagers in the 1960s but remain closed to the public due to their fragile state. A previously unknown ruin at La Penitenciaría de la Meseta was uncovered as recently as 2006.

What lies in these places and other yet to be discovered sites is tantalisingly elusive. History is traditionally written by the winners and the winners in the Chachapoya story – the Inca and then the Spanish – were notoriously unreliable narrators. Perhaps, in the coming decades, further research will fill in some of the gaps. How unified were the Chachapoya? How isolated were they from other Peruvian cultures? Were they as illustrious as the Inca? The story is still barely half written.

Brendan Sainsbury is the author of the last seven editions of the Lonely Planet Guide to Cuba.