Tyrants and Robots in Ancient Greece

Autocrats have deployed automatons as weapons since antiquity, not just in Ancient Greek myth but in reality.

Long before advances in technology made robots possible, the ancient Greeks explored the idea of creating artificial life in a series of vivid myths about androids and animated statues. As far back as Homer and Hesiod (750-650 BC), the Greeks were imagining robotic servants, life-like replicas of humans and animals, even versions of artificial intelligence (AI). Moreover, the myths reveal that, more than 2,500 years ago, people were already grappling with ethical concerns about AI and robotics that remain unresolved.

A passage in Homer’s Iliad tells how Hephaestus, the blacksmith god of technology and invention, constructed a heavenly forge with a bank of mechanised bellows, programmed to adjust their blasts according to his needs. He built automatic gates that opened and closed to admit the gods’ chariots to Mount Olympus. He also fabricated a fleet of self-propelled tripod ‘butlers’ to deliver ambrosia and nectar to the gods’ feasts. For Apollo’s temple, Hephaestus made a choir of golden women capable of singing the god’s praises. His most remarkable invention was a crew of female androids – the Golden Maidens – who served as his personal assistants. Moving about on their own, bustling to and fro in his workshop, this bevy of gilded young women anticipated the god’s every wish. Homer says they were endowed with human traits of physical strength and intelligence and equipped with divine knowledge, making them the first AI entities in western literature.

In the myths, Hephaestus’ automated devices and intelligent machines are marvels manufactured for the benefit of deities or mythic monarchs, such as King Alcinous in the Odyssey, whose palace in Phaeacia, Odysseus’ final destination, was guarded by mastiffs of gold and silver. When Hephaestus’ animated wonders are sent down to earth, however, trouble usually ensues. Consider the fate of Prometheus, the rebel Titan who stole divine fire to help vulnerable humankind. Zeus punished Prometheus by chaining him to a mountain and dispatching the monstrous Aetos Kaukasios (‘Eagle of the Caucasus’) to ravage daily his regenerating liver. Some ancient sources describe the eagle as a drone-like bronze raptor forged by Hephaestus. In his epic poem, the Argonautica, for example, Apollonius of Rhodes tells how Jason and the Argonauts observe the gleaming bird of prey returning to its crag with machine-like movements:

‘Each afternoon it flew above the ship with a strident whirr … making the canvas sails quiver to the beat of its wings. For its form was not that of an ordinary bird: the long quill-feathers of each wing rose and fell like a bank of polished oars.’

Revenge of Zeus

Prometheus was eventually freed when Zeus allowed Heracles to destroy the eagle. But Zeus’ revenge on humankind for accepting Prometheus’ gift of fire was malignant and merciless. To punish mortals, the Lord of Heaven ordered Hephaestus to fashion a kalos kakon, an evil hidden in beauty, in the form of a bewitching maiden to bring about the ruination of mortals. Each of the gods contributed to Pandora’s composition (her name means ‘all gifts’). She was sent down to earth bearing a sealed jar of misfortune and disaster, escorted by Hermes, who presented her as a bride to Prometheus’ brother Epimetheus (‘hindsight’ or ‘afterthought’). Prometheus, whose name means ‘forethought’, tried to warn his brother of the dangerous ‘gift’, but Epimetheus was charmed by Pandora and realised his error too late.

What is often overlooked in modern ‘fairytale’ retellings of the myth is the manufactured nature of Pandora. She was not simply a tragically curious young woman who could not resist opening the urn filled with grief. All the ancient versions of the myth emphasise that Pandora was ‘made, not born’. A true-to-life facsimile of a woman, she was a technological product of biotechne (‘life through craft’). Notably, Hesiod’s description of the making of Pandora echoes Homer’s words describing the fabrication of the Golden Maidens. As a seductive fembot with no past, no human emotions, no memories, no future, Pandora was made to order by a vindictive god; her sole mission to release the jar’s swarm of evils to torment mortals forever. In classical literature and art, all-powerful Zeus laughs with glee as he prepares his cruel ‘gift’ for humanity. Even the last spirit in the jar, Elpis (Hope), was not considered a boon in antiquity; hope was equated with a lack of foresight and the inability to look ahead.

Science fictions

Hephaestus’ self-moving devices remain benign only as long as they are confined to the celestial realm. Zeus, portrayed in Greek myth and drama as the tyrannical ‘father of gods and men’, ordered the eagle and Pandora, both deliberately constructed, to inflict mayhem and misery, death and destruction. The myths seem to suggest that intelligent machines, such as the Golden Maidens, are delightful to imagine as abstract, speculative ‘science fictions’ in the divine world, but that such objects would also wreak havoc in the real one.

Another myth tells of three special gifts crafted by Hephaestus for Zeus to present to his son Minos, who ruled Crete with an iron hand. It was Minos who intended the Athenian hero Theseus and his friends to be victims of the Minotaur. The three gifts from Zeus to Minos were designed to maim and slay: a golden quiver of arrows that never missed their mark; a hunting hound made of gold that always caught its prey (recalling the metallic watchdogs of Alcinous); and a towering bronze robot called Talos. Charged with the defence of Crete, Talos patrolled Minos’ kingdom, marching around the island three times a day.

Imagined as a cyborg combining man and machine, able to carry out complex human-like actions, Talos was a killer robot with an internal biomechanical system, based on divine ichor (the fluid that flows like blood in the veins of the gods) pulsating in a single tube running from his head to his foot, sealed by a nail or bolt at his ankle. Designed and built by Hephaestus, Talos was ‘programmed’ to spot strangers and to hurl boulders at ships approaching the shores of Crete. In close combat, the robot could heat his bronze body red hot. Crushing victims to his chest, he roasted them alive.

Jason and the Argonauts came close to being his victims. But the sorceress Medea discovered how to destroy Talos before he could slay Jason and his men, by removing the bronze bolt in the robot’s ankle that sealed his inner workings. Not only was Talos visualised as a technological machine, but technology was required to dismantle him. Greek vases depict Jason using a tool to remove the bolt.

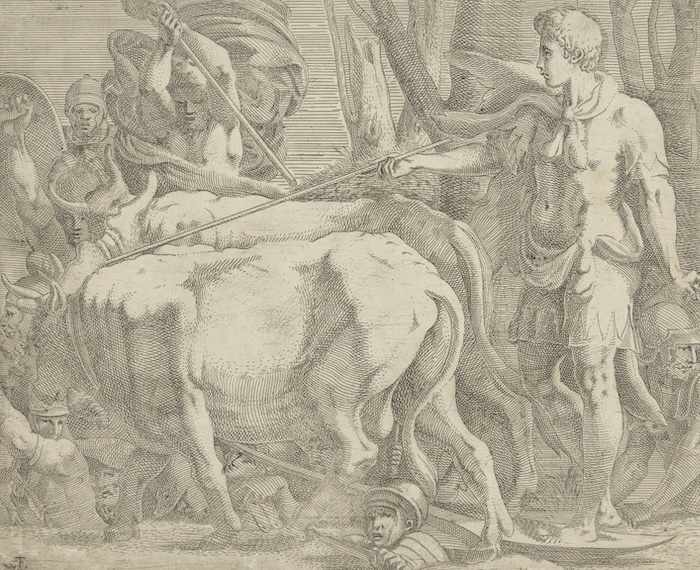

Earlier in her adventures with the Argonauts, Medea had figured out how to help Jason overcome yet another automaton-juggernaut forged by Hephaestus: the terrible Khalkotauroi. This was a pair of huge, fire-breathing bronze bulls owned by Medea’s father, Aeetes, the ruthless monarch of Colchis. King Aeetes promised Jason the Golden Fleece if he could accomplish two impossible tasks: yoke the fire-breathing bulls to a plough; and plant a field with dragon’s teeth, which would sprout an invincible army of unnatural, automaton soldiers. The king was confident that, even if Jason could somehow avoid being burned to death, he and his men would be destroyed by the unstoppable troops that would spring up from the field. Medea mixed a drug that gave Jason extraordinary physical powers to wrangle the bulls. When the beasts charged, flames shot from their nostrils ‘as though blasted by bellows from a bronze-smith’s furnace’, but Jason was able to withstand their searing breath, yoke them to a bronze plough and sow the dragon’s teeth. Sure enough, a dreadful crop of robot-like warriors clad in bronze armour rose from the furrows.

With continuous reinforcements swelling their ranks, the android warriors marched on Jason’s men. But techno-wizard Medea understood how to deal with the multiplying mob. The automatons lacked a crucial attribute: they could not be ordered or led, nor could they retreat. They were hard-wired to advance and attack. Exploiting the coding imprinted in the uncanny army, Medea instructed Jason to toss a stone to trigger the soldiers’ programming. A random impact would initiate a domino effect, a cascade of blows, causing each android to fight the nearest soldier, thereby destroying each other. As the first ranks of the dreadful army advanced, Jason threw a boulder into their midst. Sensing blows striking their bronze armour, the automatons reacted as though attacked. They turned on each other in confused frenzy, hacking at each other with their swords. Jason and his companions finished them off and escaped Aeetes’ murderous plot.

Friend or foe?

Recounting this myth more than 2,000 years ago, the sceptic Palaephatus remarked: ‘If this story were true, every general would cultivate a field like Jason’s.’ But the story’s dilemma maintains its edge today. How would automaton soldiers determine friend or foe? They could easily turn on each other or on one’s allies. How can orders be recalled or revised? The ancient myth appears to be a prescient warning that cyborg or robot armies entail problems of command and control.

One cannot help noticing that malevolent machines in ancient mythology belonged to tyrannical rulers. All-powerful Zeus took sadistic delight in devising a hideous torture-eagle to ravage Prometheus and sent Pandora to inflict suffering on humankind. These torments required the technological expertise of Hephaestus, who also constructed King Aeetes’ bronze fire-breathing bulls and King Minos’ bronze killer robot, Talos. These mythic despots used animated marvels to wield arbitrary absolute power. In fact, it turns out that the autocratic fascination with machines and life-like androids deliberately designed to harm, humiliate, torture and kill was not confined to classical myths about gods and heroes. Like their counterparts in the mythic tales, as early as the sixth century BC real tyrannical rulers in historical times and places also used cleverly designed devices and animated statues constructed to inflict pain and death.

In the myths, the ability of Talos of Crete to heat his brazen body red-hot to roast adversaries was echoed in the fire-breathing bronze bulls that threatened to immolate Jason. Perhaps it is no coincidence that a fiery bronze bull was among the torture instruments of the cold-blooded tyrant Phalaris of Acragas (now Agrigento, Sicily). Phalaris became the absolute dictator in about 570 BC. Detested for his brutality, he was overthrown in 554 BC. During his reign, the sculptor Perilaus, knowing the king’s penchant for torture, presented Phalaris with a realistic, hollow statue of a bronze bull. ‘Should you wish to punish someone’, said Perilaus, ‘just lock him inside the bull and build a fire under it. As the bull’s body heats up, the man roasts within!’ Perilaus then described the fiendish mechanism and system of pipes in the bull’s interior. While smoke and flames streamed from the bull’s nostrils, the tubes amplified the victim’s shrieks of agony issuing from the beast’s mouth, giving the impression of a bellowing, fire-breathing bull. Phalaris’ Brazen Bull was animated by the human encased inside. Impressed, Phalaris slyly requested a demonstration of the special sound effects: ‘Come then, Perilaus, show me how it works.’ As soon as Perilaus crept inside to yell into the pipes, Phalaris locked the trap door and roasted his first victim.

The Brazen Bull was described in numerous extant and lost ancient sources. In fifth-century Greece, the poet Pindar wrote, in his Pythian, of the ‘hateful reputation of the pitiless Phalaris who burned men in a bronze bull’. Aristotle, Plutarch and Polybius referred to Phalaris’ harsh reign, as did Pliny (first century AD), who castigated the sculptor Perilaus for conceiving of such a horrid use for his art and approved of his fate in the heated bull. The sculptor’s other statues, noted Pliny, were preserved in Rome ‘for one purpose only, so that we may hate the hands that made them’.

The historian Diodorus of Sicily, who viewed Phalaris’ Brazen Bull in 60-30 BC, recounted the torture device’s later history. During the First Punic War with Carthage, the general Hamilcar Barca (father of Hannibal) looted costly artworks and treasures from Sicily’s cities. His most valuable prize was the Brazen Bull of Acragas. Hamilcar Barca shipped it to Carthage in 245 BC. The Bronze Bull remained there for 100 years, until the end of the Third Punic War. It is unknown what purpose the bull served in Carthage, but one is reminded of Greek and Roman descriptions of Carthaginian sacrifices of children by burning them alive in a fiery bronze furnace inside a hollow statue of the bull-headed deity Ba’al Hammon (Moloch).

When the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus finally defeated Carthage in 146 BC, he restored all the plundered treasures to Sicily, including the Brazen Bull. Scipio pointedly declared that the bull was a monument to the barbarism of Sicilian tyrants, such as Phalaris. In 70 BC, Cicero noted that the Bronze Bull, which ‘the most cruel of all tyrants had used to burn men alive’, was still standing in Acragas.

Burning victims

Phalaris was not the only malicious ruler to own a realistic statue morbidly ‘brought to life’ by internal mechanisms that broadcast the screams of the burning victim. A similar statue for roasting people alive was a life-like bronze stallion forged by Arruntius Paterculus for the Sicilian tyrant Aemilius Censorinus, who rewarded artisans for inventing novel torture contraptions. A large, hollow bronze statue in the form of a man, perhaps inspired by the mythic Talos’ burning embrace, was used in the same manner by the tyrant Agathocles of Segesta in about 307 BC. The practice continued into Late Antiquity. According to Christian accounts, at least four martyrs were burned inside life-like metallic bulls belonging to various oppressive rulers. The last known victim was himself a despot, Burdunellus of Zaragoza, Spain, executed in Toulouse in AD 496 by being ‘placed inside a bronze bull and burnt to death’.

It is not clear whether the ancient copies of Phalaris’ Brazen Bull were also equipped with the internal pipes to amplify the victim’s agony and bring the bull to ‘life’. It is interesting that Phalaris was a Rhodian and his city of Acragas was a colony of Rhodes. We know that the Greek island was renowned for its many animated statues and even boasted a pair of ‘bellowing’ bronze bulls that served as an early warning system against invaders. As with the Brazen Bull, a set of internal tubes and pipes amplified a watchman’s shouts into the bellowing sound effect of the guardian bulls of Rhodes. Greek and Latin sources describe singing, laughing and shouting statues, as well as those that could lift their arms, turn their heads, blink, bleed, sweat and cry.

These animated statues did not cause harm but were intended to evoke awe, dazzle, entertain and impress ordinary viewers with the power of the gods and their representatives on earth. Yet the preponderance of animated imitations of nature deliberately fashioned to inflict pain in antiquity seems to outweigh the charm of automatons for pleasure, whether one considers myth or history.

The deadly animated bronze statues designed for torture allowed historical tyrants in the classical world to show off their wealth and might and to exert what appeared to be superhuman, god-like powers over their subjects. History does record one spiteful despot, who displayed his power nonviolently with a self-moving marvel in Athens. The giant animatronic land snail that led the Great Dionysia Festival procession in Athens in 308 BC may seem a simple prank at first glance. It was commissioned by Demetrius of Phaleron, a tyrant imposed on Athens by the Macedonians. Demetrius ruled from 317 to 307 BC. He reportedly conceived of the Great Snail as a novel way to taunt the disenfranchised citizens of Athens. The Snail had internal workings that made it move on its own, excreting a trail of slime over the traditional route of the procession. Directly behind the Snail was a contingent of asses. Everyone knew that snails were proverbially slow creatures, so destitute and lowly that they bore their homes on their backs, while asses symbolised stupidity and laziness. The grotesque spectacle of the colossal Snail at the head of the city’s most sacred procession was a dramatic and public way to humiliate the Athenians, once famed for their quickness and intelligence, but whose democracy was being crushed by the Macedonians and their allies.

A century later, in 207 BC, the malevolent dictator Nabis seized power in Sparta, ruling the territories of Laconia and Messene until he was assassinated in 192 BC. The reign of Nabis and his wife, Apega, was long remembered for the vicious extortion, torture and executions of masses of their subjects. According to Polybius, Apega ‘far surpassed her husband in cruelty’. When Nabis dispatched Apega to Argos to raise funds, for example, she personally tortured women and children until they gave up their gold, jewels and other costly possessions.

Inspired by his wife’s brutal deeds, Nabis ordered an artisan-engineer to make a mechanical facsimile of Apega, a ‘machine that resembled his wife with extraordinary fidelity’. As the historian of Spartan women Sarah Pomeroy remarks, Nabis’ intention was to ‘invent a female robot as evil and deceptive as Pandora’. The life-like animated figure was clothed in Apega’s expensive finery and we might guess it featured a painted plaster or wax cast of Apega’s own face, like the portrait masks made by ancient artists and sculptors.

Studded with spikes

Nabis would summon citizens and ply them with wine, while urging them to turn over their property. If a guest refused, Nabis would say: ‘Perhaps my queen Apega will be more successful in persuading you.’ The inebriated guest was then taken to ‘meet’ the replica of Apega. When he offered his hand to the seated ‘Apega’, the robot stood up, triggering springs to raise her arms. Standing behind Apega, Nabis then manipulated instruments in her back to cause her arms to suddenly to clasp the victim. The fancy clothing hid the fact that the replica’s hands, arms and breasts were studded with iron spikes. Working levers and ratchets, Nabis tightened Apega’s deadly embrace, drawing the victims closer by degrees, driving the spikes deeper into their bodies. With this impaling device in the form of his wife: ‘Nabis destroyed a good number of men who refused his demands’, wrote Polybius.

By the fourth and early third centuries BC, military engineers in Italy, Carthage and Greece had developed crossbow artillery and powerful torsion catapults based on complex mechanical formulas and springs. Meanwhile, Greek artisans and inventors at Alexandria in Egypt, were designing and producing a fantastic panorama of spectacular automatons. Many of these – including a 15ft-tall woman who periodically rose from her seat and poured a jug of milk – were displayed during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadephus in his Grand Procession of about 279 BC. Given this rich legacy of classical and Hellenistic inventions, it seems safe to assume that Nabis’ lethal Apega machine was modelled on technological precedents. The Apega automaton was not heated but killed its victims by forcible embrace, recalling the way Talos crushed people to his chest. Some have postulated that Nabis’ diabolical Spartan machine was an inspiration for the imaginary medieval torture device, the Iron Maiden.

Modern engineers are manufacturing robots and AI entities more than 2,500 years after mythic tales of the AI-endowed Golden Maidens, animated bronze statues of animals and humans, drone-like raptors, automaton warriors, self-propelled tripods and the replicant Pandora were circulating in ancient Greece and millennia after real inventors in the ancient world were beginning to design and build animated machines. As in antiquity, the use of such entities to interact with human beings raises serious ethical concerns and fears. Today’s military scientists are creating cyborg-robot soldiers and self-driving weapons at speeds that outstrip our ability to work out the practical and moral issues that surround such wonders. Spinning the archaic myth of the super bronze robot Talos into modern warfare, the first surface-to-air missiles were named after Minos’ bronze guardian of Crete. Also inspired by mythical automatons, the US Pentagon’s DARPA scientists are developing TALOS, a weaponised and armoured AI exoskeleton for battle.

Dominance and submission

The timeless fascination of tyrannical rulers for automatons, in both myth and ancient history, was often related to a drive to dominate and exert overwhelming power. With those tales in mind, it seems fair to ask whether we can avoid repeating Epimetheus’ short-sighted mistake of welcoming Pandora and her jar before we understand the risks. Chilling queries arise: who is advocating and commissioning weaponised automatons? How long until military engineers create robots to carry out interrogation, torture and assassination, as well as combat? Robotic science itself is not the problem, rather it is the motives of those who control it for their own purposes. The mythic and historical accounts suggest that humans need to be willing and able to take responsibility for advanced technology and avoid turning over the future to tyrants.

As an antidote to this melancholy roster of malevolent automatons in classical myth and history, let us conclude with an example of a benevolent ruler: Archytas of Tarentum, a Greek colony in the heel of Italy (modern Puglia). A philosopher-scientist-statesman who happened to be a brilliant engineer and inventor of animated devices, including the first self-propelled flying machine in the shape of a bird, Archytas (428-347 BC) was widely admired for his intelligence and virtue. The citizens of democratic Tarentum elected Archytas to the high office of strategos seven years in a row. A friend of Plato, some scholars believe Archytas was a model for the idea of philosopher kings in the Republic.

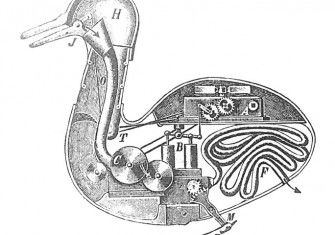

Aristotle referred to Archytas’ engineering theories and mathematical mechanics in several treatises, but Archytas’ own writings no longer survive except in fragments. Horace addressed a poem to Archytas in his Odes and many ancient sources discuss him. But the Latin author and grammarian Aulus Gellius (writing in the second century AD) is the only surviving author to describe the celebrated self-propelled flying Dove fabricated by Tarentum’s head of state more than 2,300 years ago. What the ‘mechanician’ Archytas ‘devised and accomplished is marvellous but not impossible’, commented Aulus Gellius. Citing the philosopher Favorinus, ‘a studious researcher of ancient records’, Aulus Gellius reported that Archytas ‘made a flying wooden model of a dove in accordance with mechanical principles’. The Dove was ‘balanced with counterweights and moved by a current of air enclosed within it’. The bird flew some distance, but ‘when alighted it could not take off again’. Further details are lost, because the passage breaks off here and the rest of Aulus Gellius’ text has not survived.

Archytas’ pioneering work on mechanical mathematics, cubes and proportions allowed the creation of scale models, such as the Dove. Much has been written by modern philosophers and historians of science on Archytas’ principles of mechanics. A striking glimpse into his personality comes from Aristotle. Alongside his impressive military, political and scientific accomplishments in mathematics, geometry, harmonics and mechanics, Archytas took the time to invent a popular children’s plaything, the clacking noisemaker known as the ‘clapper’. His toy and his technological showpiece, the flying Dove, demonstrated mechanical principles while providing a delightful diversion for his fellow citizens – and provides a welcome alternative to the cruel automatons employed by dictators of antiquity. Of course, Archytas was a democratically elected leader, not a typical tyrant – perhaps that makes all the difference.

Adrienne Mayor is a Berggruen Fellow 2018-19, Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University.