Titanic: Southampton’s Deep Sorrow

The impact of the Titanic disaster on Southampton, the city from which it sailed and home to more than a third of those who lost their lives, was immense.

The sinking of RMS Titanic traumatised the city of Southampton, the port she sailed from, rendering it nearly mute on the subject for many years afterwards. George Bowyer, the harbour pilot in charge of the liner as she embarked on her maiden voyage, omitted the most significant event of his life, when in 1931 he published his memoirs (Lively Ahoy: Reminiscences of 58 Years in the Trinity House Pilotage Service). Titanic became a taboo subject in the offices of its owner, the White Star Line, and was spoken of discreetly, if at all, on Southampton’s streets, few of which escaped association with the most infamous disaster in maritime history.

A total of 549 people (including 12 passengers) with Southampton addresses lost their lives, more than a third of the overall death toll. Southampton provided the bulk of Titanic’s crew and for many Sotonians the tragedy became a family memory. Not all of them were permanent residents but 360 were listed in the 1911 census as living in the city. The last living survivor, Millvina Dean – just nine weeks old at the time of the disaster – died as recently as May 2009. Her family was moving to Kansas where they planned to open a tobacconist shop. Her father died in the sinking and Millvina, her mother and brother returned to Southampton, where she remained for most of her life.

Southampton’s fate and prosperity have been built on the sea. A hundred years ago it was the home port of more than 20 steamship companies and a sizeable proportion of its 120,000 inhabitants, some originally from other parts of Britain and Ireland, found work on the ships. In the early months of 1912 a coal strike had led to several vessels being confined to the docks and their crews laid off. Consequently jobs on Titanic’s maiden voyage were particularly prized.

There were no permanent crews aboard passenger liners at the time. The captain and officers received a salary from the shipping line but the deck crew, stokers, stewards and others signed on before each voyage, were paid for that voyage only and had to enlist afresh for subsequent trips.

Most of Titanic’s crew came from the neighbourhoods of Northam and Millbrook and from the slightly more prosperous district of Shirley. Here six of the victims lived in one short suburban street, Hanley Road, and their fates tell a wider story about the disaster and its aftermath.

At No. 1 lived a man in his early 20s, Cyril G. Ricks, who signed on as a storekeeper. According to a fellow crew member, he jumped from the stern of the ship just before it sank but was hit by falling debris and died shortly afterwards. His body was recovered by the Mackay-Bennett, one of the ships that sailed to the disaster scene from Halifax, Nova Scotia. Ricks was buried at sea on April 24th. Another victim, 28-year-old Ernest Roskelly Olive, lived at No. 37 with his parents and sister and signed on as a ‘clothes presser’. He died in the disaster and his body, if recovered, was not identified.

No. 5 was the address of Ernest Edward Samuel Freeman, who joined the Titanic for the delivery trip from Belfast, where she was built. She arrived in Southampton on April 3rd and spent the following week taking on provisions, some 900 crew and, finally, 1,300 passengers. Freeman, in his mid-40s, signed on as a ‘deck steward’ for a monthly wage of £3.15s. However, he is usually referred to as the secretary of J. Bruce Ismay (the Old Harrovian chairman of the White Star Line) due to the recognition that Ismay later accorded him.

Doubt over Freeman’s status lingers because Ismay, who often joined his ships on their maiden voyages, was accompanied in this instance by his official secretary, William Henry Harrison, listed as a first-class passenger. The confusion may shed light on one of the controversies of the Titanic tragedy: the conduct of Ismay as the lifeboats were being filled and lowered.

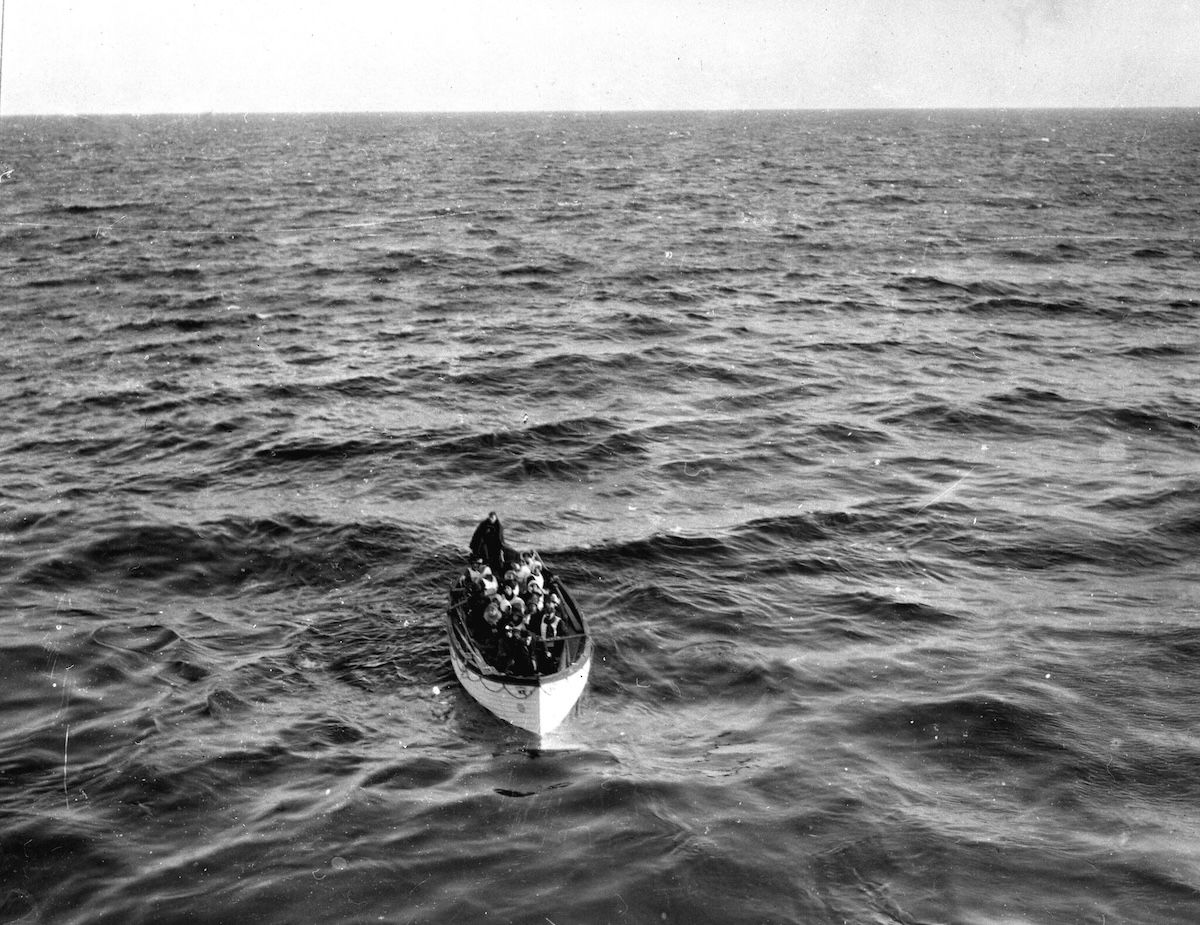

The overriding reason for the massive loss of life on Titanic was the lack of lifeboats. The 20 she was equipped with (including four collapsibles) could accommodate only half the number of people on board and some were not even filled to capacity. In the aftermath of the disaster much was made of the principle of ‘women and children first’, but the truth is that nearly as many men in first class were saved as children in third class.

Ismay survived by boarding the lifeboat known as Collapsible C and, along with the other survivors, was picked up by RMS Carpathia and taken to New York. Both Freeman and Harrison drowned. When their bodies were recovered by the Mackay-Bennett Freeman’s personal effects were listed as memo book, glasses, pipe, pouch, knife and gold watch. There was sixpence in the pocket book. Harrison had on him £10 in gold, nearly £2 in coins and £10 in banknotes.

The Mackay-Bennett was one of several cable ships – usually used to repair underwater telegraph cables – chartered by the White Star Line in Halifax to retrieve the dead. It was a grisly business. Loaded with ice, coffins and embalming fluid, they took three days to reach the site of the sinking. The Halifax ships recovered 328 bodies of which 119 were buried at sea. The rest were returned to Halifax, which now fulfilled the roles of undertaker and mourner. Church services were held, bells tolled and graves were dug. Fifty-nine bodies were reclaimed by their families. The remaining 150 were buried in three cemeteries: Fairview, Mount Olivet and Baron de Hirsch. Ernest Freeman and William Harrison lie in Fairview, two of just a handful of identified victims – most of the granite grave markers are simply inscribed ‘Died April 15th, 1912’, followed by a number that corresponds to the order in which they were pulled from the sea.

Freeman’s headstone is one of the largest in Fairview. It bears the inscription:

He remained at his post of duty

seeking to save others

regardless of his own life

and went down with his ship.

A further line tells us that the stone was erected by Ismay ‘to commemorate a long and faithful service’. Conceivably this was part of an effort by Ismay to assuage his guilt, for he was denounced as a coward when news began to circulate of the circumstances of his survival. No one can be sure of his actions or motives on the boat deck of Titanic but many people made up their own minds. Ismay kept a low profile for the rest of his life and died in London in 1937.

Back in Southampton a relief fund was set up for the widows and orphans of the victims and money-raising events were held throughout Britain. Ernest Freeman’s family were beneficiaries of the fund and Ismay also provided them with a private pension. The parents of Cyril Ricks were in receipt of £218 from the White Star Line under the Workmen’s Compensation Act. Under the same act the father of Ernest Roskelly Olive claimed he had been partially dependent on his son to the tune of £1 a week but his case was dismissed. In 1954 there were still 94 dependants of the Titanic Relief Fund.

The following year Walter Lord’s classic account of the Titanic disaster, A Night to Remember, was published, based on interviews with survivors. It was followed in 1958 by the film of the book. These helped to revive a worldwide interest in the Titanic story. After almost half a century the hush that one resident recalled descending on Southampton, as news filtered through of the enormity of the tragedy, began to lift.