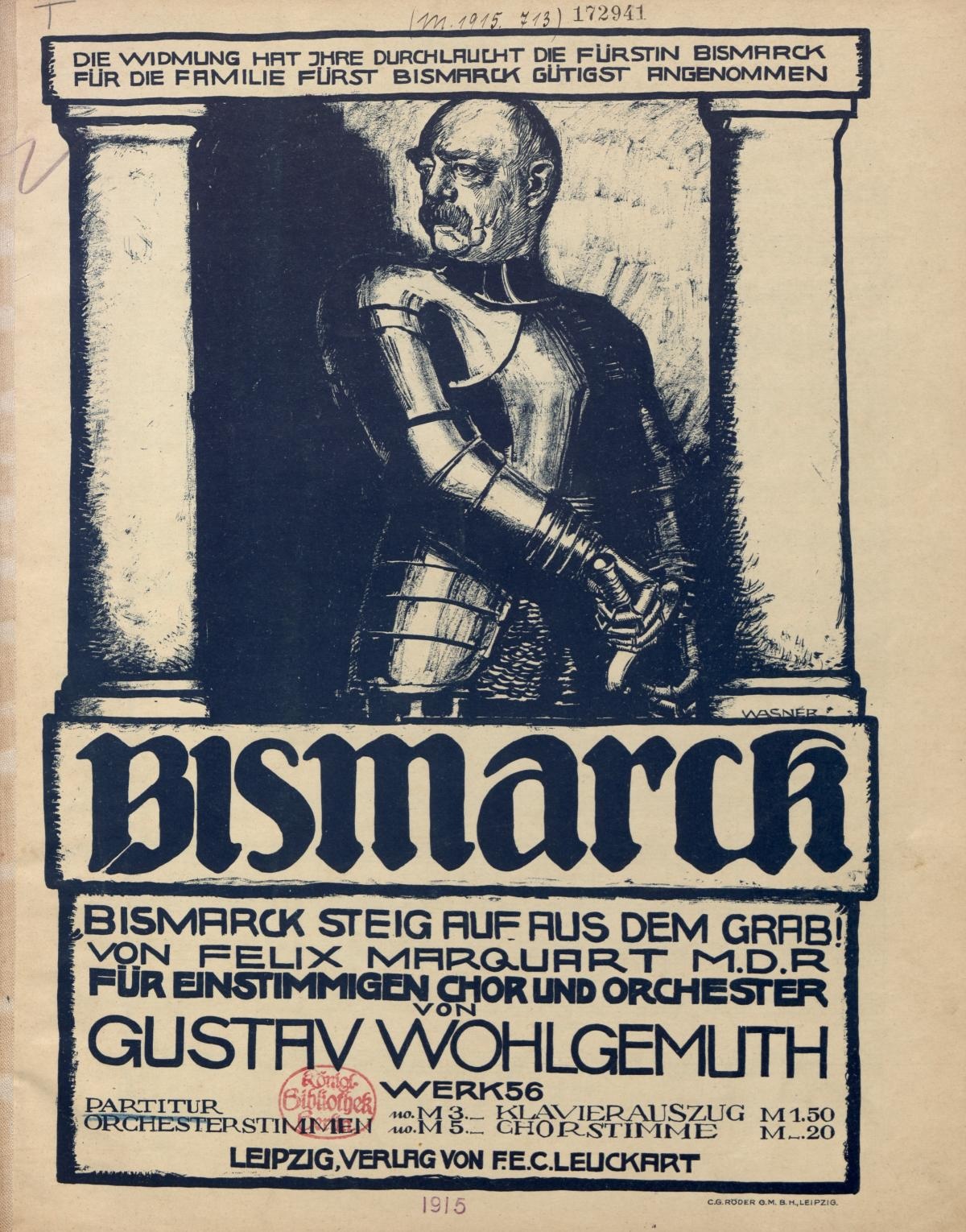

Otto von Bismarck and the German Right

After he fell from power, Bismarck became a mythical hero figure of the right. The legend of the ‘Iron Chancellor’ was wielded by militarists, conservatives, and eventually, Adolf Hitler.

In early July 1944, barely three weeks before the attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler by Claus von Stauffenberg, one of the leading members of the German resistance movement, Ulrich von Hassel, travelled through the war-torn Third Reich to visit the birthplace of Otto von Bismarck (1815-98) in the north German village of Friedrichsruh. Horrified by the destruction unleashed by Nazi Germany and convinced that Hitler would ultimately destroy Bismarck's proud Reich of 1871, von Hassel noted in his diary: