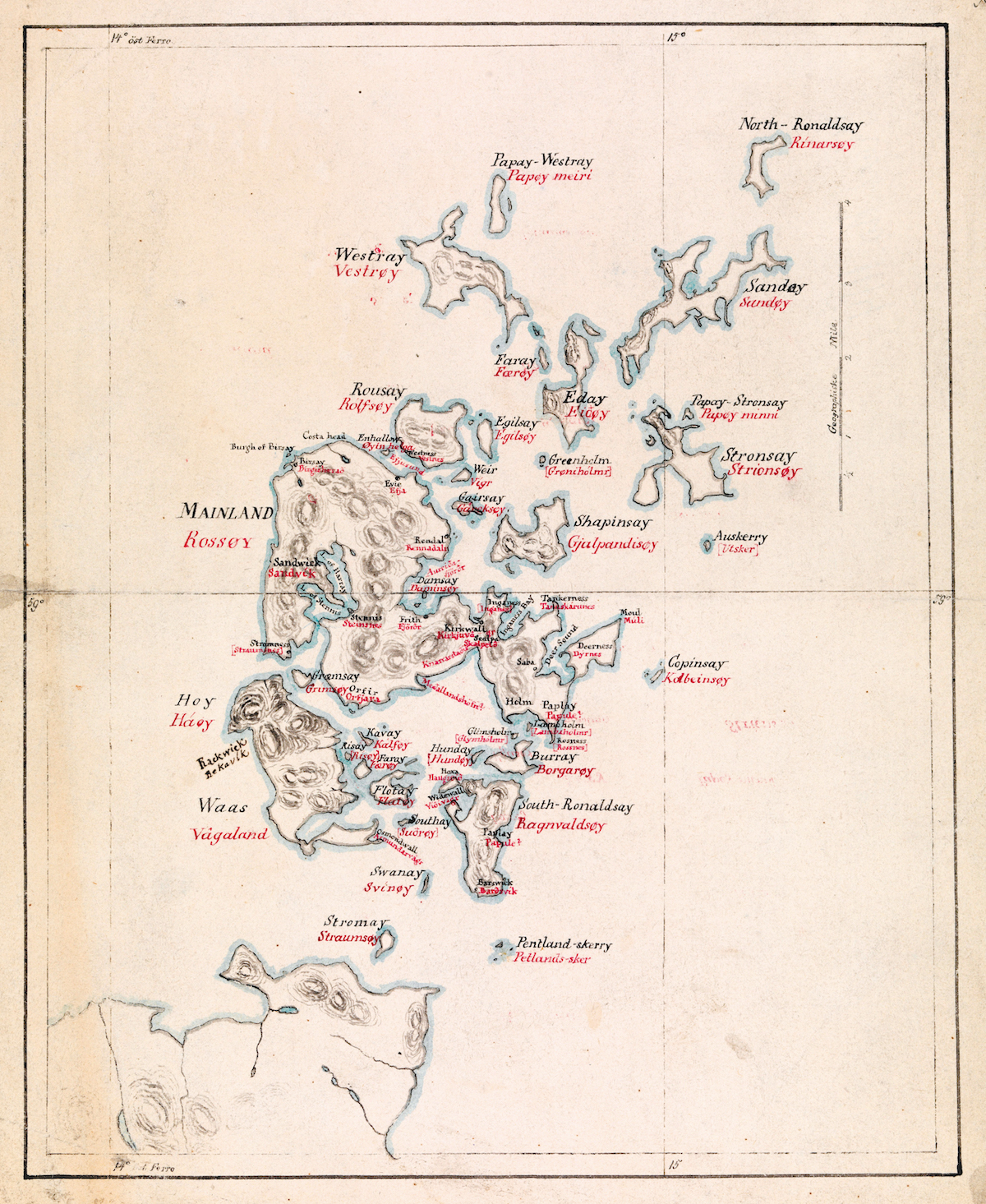

Orkney’s Saga: the Islands between Kingdoms

Is Orkney Scandinavian or Scottish? Having passed from the former to the latter during the Middle Ages, for centuries the Danish Crown sought to take the islands back.

In July 2023 the Orkney Islands, lying just off the northeast coast of Scotland, made headlines around the world after the local council voted to explore ‘alternative forms of governance’. One option under consideration, it was widely reported, was for Orkney to secede from Scotland and the United Kingdom to become a self-governing territory of Norway. In reality ‘Orxit’ was not an imminent prospect, and the council’s move was something of a political stunt to underline frustration in the islands with the Scottish government’s policies concerning ferry subsidies.

One result of the furore, however, was to remind the rest of Britain about something the people of Orkney have always been acutely aware of. The islands have strong historical links to Scandinavia, and for hundreds of years represented a frontier zone, a fragile northern border of Britain. At the end of the Middle Ages control of Orkney, along with Shetland further to the north, passed from Norway to the kingdom of Scotland. But, through the centuries that followed, the legal and constitutional position of the islands remained unsettled and at times fiercely contested.