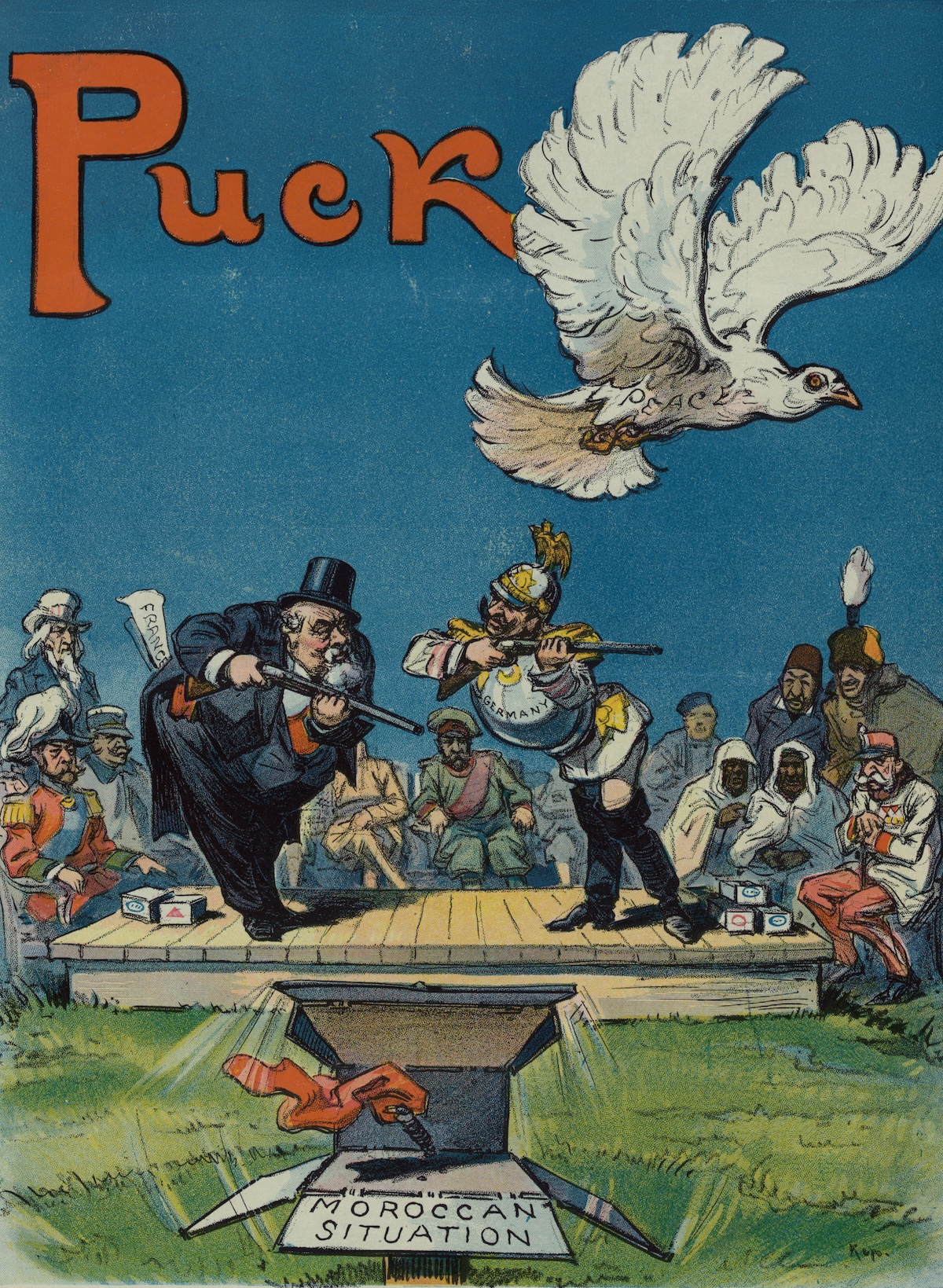

The German Panther at Agadir

The Agadir Crisis of 1911 was one of several incidents that raised international tensions between Germany and France in the years before the First World War.

Panther at the Moroccan port of Agadir on July 1st, 1911, provoked a crisis in diplomatic relations between France, Britain and Germany, symptomatic of the steady deterioration in trust between the European great powers in the years before the outbreak of the First World War. It also led to the signature of the Convention of Fez in March 1912 by which France assumed a formal protectorate over the Sultanate of Morocco and thus acquired the third and final piece of her North African empire. The short-term implications were therefore of interest to all the governments of the great powers, who were quick to grasp the opportunity to use this relatively minor incident to establish claims of priority of interest, influence and compensation.