Deeds Not Words: Slashing the Rokeby Venus

From the suffragettes to Just Stop Oil, Britain’s National Gallery – specifically Diego Velásquez’s Rokeby Venus – has been a magnet for attack by activists. Why?

The Rokeby Venus, by Diego Velázquez, as it appears today in the National Portrait Gallery. Diego Delso/delso.photo (CC-BY-SA).

Today, the celebrated nude by the Spanish painter Diego Velásquez, known as the Rokeby Venus, is one of the most popular paintings on display at the National Gallery. But the acquisition of the Venus was no easy task. Since 1809 its home and namesake had been Rokeby Park, a large Palladian house belonging to John Morritt, a good friend of the novelist Sir Walter Scott. Morritt would gleefully write to Scott of his efforts to rearrange his paintings to make room for ‘my fine picture of Venus’s backside’, finally deciding upon a position above the mantelpiece, where it raised the image ‘to a considerable height the ladies may avert their downcast eyes without difficulty and connoisseurs steal a glance without drawing said posterior into the company’.

In 1906, following three years of negotiations and a successful fundraising effort headed by the National Art Collection Fund, the National Gallery purchased the Rokeby Venus. The gallery was faced with the same choice as Morritt, 94 years prior: where to place the beloved backside. This time it was hung at eye-level, accessible and perfectly positioned to be viewed by admirers. But not everyone admired the painting. By 1914 the country was in the midst of a long-running fight by the women’s suffrage movement for the right to vote, and public protests were beginning to turn violent. The year before had marked a dramatic escalation in arson attacks and vandalism which involved window-smashing, letter bombs and the desecration of golf courses.

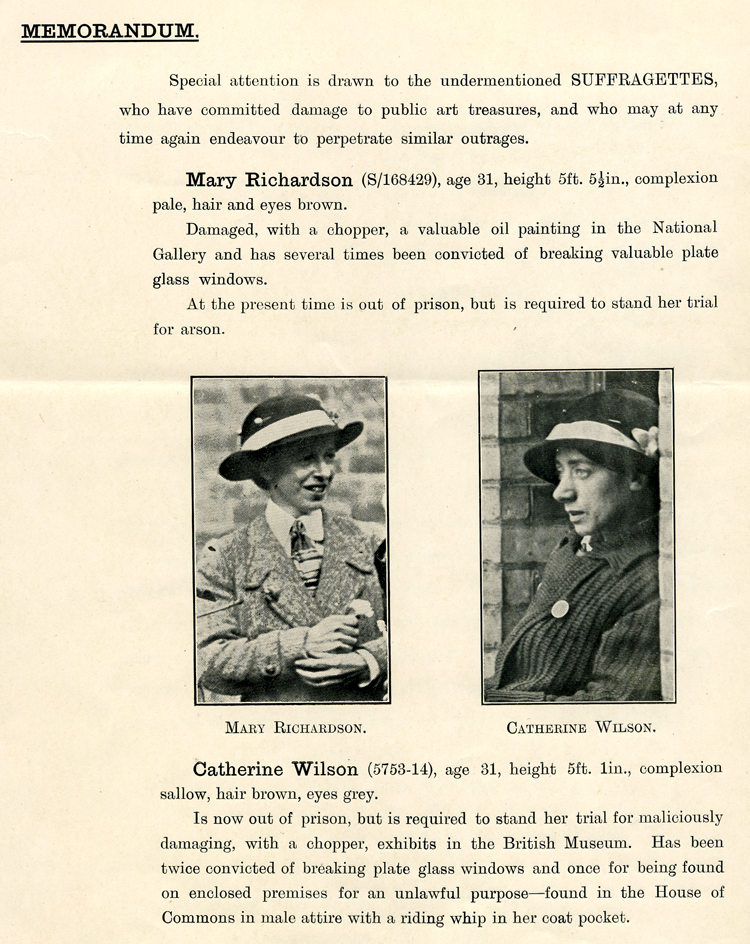

One suffragette who was beginning to make a name for herself in the movement was art student and journalist Mary Richardson. As she claimed in her autobiography Laugh a Defiance (1953), Richardson attended the 1913 Epsom Derby and mustered the courage to wave a copy of The Suffragette newspaper as the royal guests were welcomed. She was met with ‘scornful glances’, but no violence – at first. Then, at the end of the third race, she witnessed an acquaintance of hers in the crowd, Emily Davidson, suddenly charge onto the racecourse carrying a suffragette flag, before being immediately cut down and flung across the ground by the king’s horse. Richardson recalled the pandemonium that followed; a man seized the newspaper she had been waving and began to hit her with it, prompting a mob to pursue her. According to Richardson, she was able to escape with the assistance of a porter at the nearby train station, who helped her escape by hiding her in a lavatory.

There exists no other contemporary evidence to suggest she was present at the Derby, but the incident clearly had a profound effect on Richardson. After accumulating a series of convictions and stints in prison for public vandalism and assaulting a police officer, Richardson decided to take things a step further:

I had to draw a parallel between the public’s indifference to Mrs Pankhurst’s slow destruction and the destruction of some financially valuable object. A painting came to mind. Yes, yes - the Venus Velasquez had painted, hanging in the National Gallery.

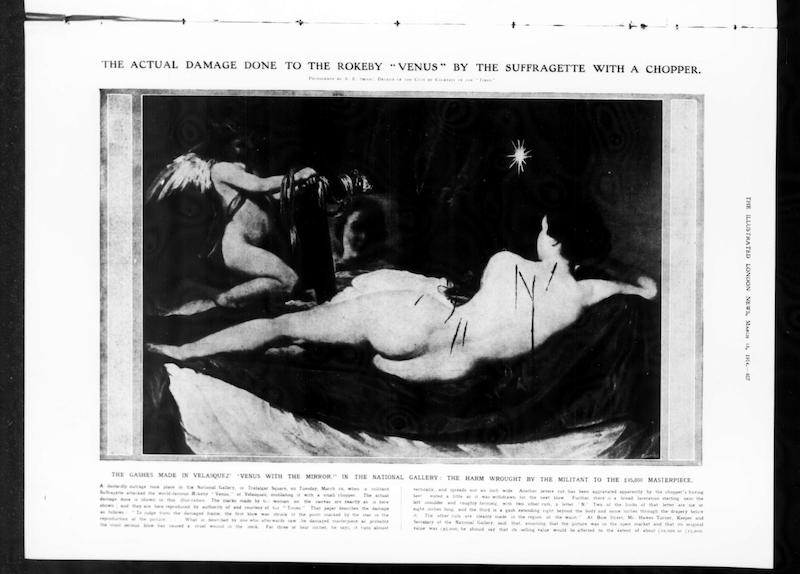

Nine months later, on 10 March 1914, Richardson visited the gallery, sketchbook in hand to appear inconspicuous. As she idly sketched the Madonnas that surrounded her, she took note of the attendants and plain-clothes detectives guarding the Venus. After two hours of waiting for the perfect moment, Richardson withdrew a meat cleaver from her coat, ran towards the painting and launched her attack. Attendants were slow to react; as she recalls, one fell to the ground as he attempted to charge her, while another stared up at the skylight in bewilderment. The damage to the Rokeby Venus was significant: Richardson had aimed her strikes upon the body of the Venus specifically, leaving deep, gaping cuts in the canvas. The media quickly seized upon the story, dubbing Richardson ‘Slasher Mary’, a name that evoked the colourful monikers given to notorious female killers in late-19th-century England, such as the 'Black Widow' (Mary Ann Cotton) and the 'Ogress of Reading' (Amelia Dyer). The oil-painted Venus was turned into a living, breathing victim, with her ‘slashed’ figure exhibited across newspapers like a body at a murder scene. Richardson remembers a conversation she had during her subsequent incarceration with the woman cleaning her jail cell, who remarked, ‘My word, you didn’t half cut ’er up.’

What made the Venus such a coveted and prized possession was not simply its beauty as a work of art, but also the miraculousness of its very existence. It remains Velásquez’s only surviving female nude, painted in the wake of the Spanish Inquisition’s orthodox dominion over 17th-century Spain, that restricted the circulation of images containing nudity. This, of course, did not stop the wealthiest of art patrons from amassing an immense collection of sensual portraits. King Philip IV, of whose court Velásquez was the leading artist, collected over 4,000 paintings during his lifetime. He was also a great admirer of the Flemish painter Rubens, well-known for his depictions of curvaceous mythical muses and goddesses.

Nonetheless, nudes at this time were rarely put on public display, kept instead in discreet rooms of the rich and powerful known as sala reservadas, where erotic art could be admired – in private. This only adds another layer to the symbolic intensity behind Richardson’s act of vandalism: destroying the image of a woman that had been gawked at lasciviously by affluent men for centuries. She herself stated in a later interview that she didn’t appreciate how ‘men visitors gaped at it all day long’. Other suffragettes took note of how Richardson used the fame of the Rokeby Venus and the ensuing media circus as a platform for the cause, and, despite renewed efforts to beef up security in London’s galleries in case of copycat attacks, another painting in the National Portrait Gallery suffered a similar assault just two months later. This time it was a portrait of Thomas Carlyle by John Everett Millais which met the sharp end of a butcher’s tool held by suffragette Anne Hunt, labelled a ‘hatchet fiend’ by the press.

Anne Hunt’s argument in court was eerily prophetic, stating that the honour bestowed by ‘the attention of a Militant’ had given the painting greater value and historical importance. It is hard to disagree with this notion, when today both the Carlyle portrait and the Rokeby Venus are just as famous for their subject matter as they are for their violent histories. Irrespective of the criminality of the act itself, a painting that has been vandalised, especially on multiple occasions, earns a certain aura; there is something disturbingly poetic about any artwork that inspires such emotion in viewers that they feel compelled to destroy it. Even art galleries have had to acknowledge this in their displays. In 2018 the restored Carlyle portrait was displayed alongside a photograph of the earlier damage at the same gallery in which it was attacked over a century earlier, as part of an exhibition that commemorated key figures in the women’s suffrage movement. And Mary Richardson’s name was revived in the British press once again in November last year, when the Rokeby Venus was attacked by Just Stop Oil activists who smashed the painting’s protective glass with safety hammers and declared: ‘Women did not get the vote by voting. It is time for deeds, not words.’

Looking at the Rokeby Venus today, the marks from Richardson’s ‘chopper’ are difficult to see with the naked eye, but a closer look shows remnants of the fading scars, indicated by a slight discolouration drawn across her spine. Whether Richardson’s demonstration was warranted or even successful remains up for debate, but what is undeniable is that the Venus, who after 300 years still lies relaxed and imperturbable before her mirror despite everything, would not be the woman we still gaze upon and admire today without it.

Ellen Walker is a freelance writer and illustrator, and a PhD researcher at the Royal College of Art in London.