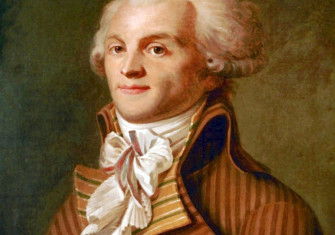

The Birth of Robespierre

Richard Cavendish charts the life of Robespierre, who was born on May 6th, 1758.

Unforgettably described by Carlyle as 'the Sea-Green Incorruptible', Maximilien-François-Marie-Isidore de Robespierre was born in the town of Arras in north-eastern France, the eldest child of a lawyer. The 'de' in his name he would eventually drop. There is talk of Irish ancestry far back, but his family had long been French. The new arrival was born only four months after his parents' wedding and there were later two sisters, Charlotte and Henriette, and a younger brother, Augustin.

Maximilien lost his mother when he was only six. She died at twenty-nine, giving birth to a fifth baby. He also lost his father who abandoned the children and wandered off. According to Charlotte's later recollections, her brother could never afterwards think of his mother without tears and one consequence was that, unlike most French Revolutionary leaders, he knew at first hand what being poor was like.

He and Augustin were brought up by their mother's parents and sent to school as charity boys in Arras. At eleven Maximilien won a scholarship to a prestigious school in Paris, Louis-le-Grand College, where he learned to admire the Roman Republic and such figures as Cato and Cicero. He also came to revere Jean-Jacques Rousseau and to lose confidence in Roman Catholicism. A fellow-student who would also play a leading role in the Revolution was Camille Desmoulins.

Robespierre did brilliantly in classics, so that in 1775 he was selected to deliver the official address in Latin verse to welcome Louis XVI when he and Marie Antoinette visited the school on the way back from their coronation in Rheims. The King and Queen were late, kept everyone hanging around for hours in pelting rain, sat in their coach all through the ceremony and departed as hastily as possible with smiles, but not a word in reply or even an approving nod.

In 1781 Robespierre went back to Arras to set up as a lawyer while Charlotte kept house for him. He would never marry, though Charlotte said he was attracted by and attractive to women and he courted several, including Eleanore Duplay, the eldest daughter of the cabinet-maker in whose house in Paris he lodged in the 1790s. His practice was only moderately successful. He seems to have been a friendlier and more companionable person than his later reputation suggested, though according to Charlotte there was a deep reserve in his character. He joined the Rosati club of aesthetes, who met for summer picnics to extemporize verses on themes of life and love, as well as the Arras literary academy. But his insistence on representing poor clients against the rich alarmed the privileged classes. He made no secret of his disapproval of absolutism and his concern for justice and equality.

When in 1789 the king summoned a national assembly, the Estates-General, Robespierre was elected as one of the representatives from Arras and began his career in national politics. He attended the first meeting of the Third Estate on May 5th, 1789, the day before his thirty-first birthday. Although physically unimposing, with a weak voice and facial tics, Robespierrre swiftly made an impression. All his life he lived frugally and dressed simply and neatly; his manners were unostentatious.

A leading member of the leftwing Jacobin Club, he was not disturbed by the massacres of imprisoned aristocrats and priests in Paris in 1792 and he demanded the execution of Louis XVI. From 1793 he was the most prominent figure in the Committee of Public Safety, which introduced the Terror and the cult of the Supreme Being. Concern for justice and equality had turned into tyranny and terror. More recent historians have been kinder to Robespierre than Carlyle was, but his combination of high principles and ruthlessness roused fear and in 1794 his enemies denounced him and he was sent to the guillotine to which he and his colleagues had consigned so many others. He was thirty-six.