Hogarth’s New Britain

The painter’s reaction to the Jacobite Rebellion is more than mere satire.

In the winter of 1745 Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s attempt to overthrow the House of Hanover and restore the House of Stuart to the thrones of Great Britain and Ireland seemed unstoppable. On September 21st the only British troops available to crush the nascent rebellion in Scotland were routed by a predominantly Highland Jacobite army at the Battle of Prestonpans. By late November ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ and his troops had marched south to Manchester, while two armies commanded by Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and Field Marshal George Wade were attempting to stop their advance. On December 4th Charles and his army entered Derby, about 120 miles north of London. Two days later, on what became known as ‘Black Friday’, news reached the capital. Orders were issued that all Grenadier Guards should march immediately to the encampment at Finchley Common. If Cumberland and Wade failed in their task, these troops would be the last barrier between the Stuart prince and London.

In the winter of 1745 Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s attempt to overthrow the House of Hanover and restore the House of Stuart to the thrones of Great Britain and Ireland seemed unstoppable. On September 21st the only British troops available to crush the nascent rebellion in Scotland were routed by a predominantly Highland Jacobite army at the Battle of Prestonpans. By late November ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ and his troops had marched south to Manchester, while two armies commanded by Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and Field Marshal George Wade were attempting to stop their advance. On December 4th Charles and his army entered Derby, about 120 miles north of London. Two days later, on what became known as ‘Black Friday’, news reached the capital. Orders were issued that all Grenadier Guards should march immediately to the encampment at Finchley Common. If Cumberland and Wade failed in their task, these troops would be the last barrier between the Stuart prince and London.

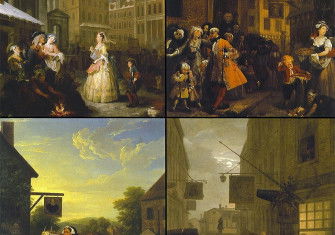

This is the starting point for William Hogarth’s The March of the Guards to Finchley (pictured above). However, it is not intended as an accurate depiction of events on Black Friday; there is an element of satire, directed chiefly at an unprepared British government and army, within the chaotic scene at Tottenham Court turnpike. But satire is not Hogarth’s sole aim. After all, it was painted between 1749 and 1750, in the knowledge of the defeat and aftermath of the rebellion, when the old Highland clan system, seen as the lifeblood of the Stuart cause in Scotland, was dismantled. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in October 1748 ended hostilities between Britain and France, so that no French-sponsored attempt to restore the Stuarts was now likely. The treaty also specified that the Stuarts, Charles (then in Paris) in particular, should be expelled from French territory. By 1750, then, the Jacobite threat seemed to have passed.

A commentary originally in French, written by Hogarth’s friend André Rouquet, offers an alternative view of the mayhem within the composition:

Discipline is less observed in the principal Design, but if you complain of this I must ingenuously inform you, that Order and Subordination belong only to Slaves; for what every where else is called Licentiousness, assumes here the venerable Name of Liberty.

The display of collective and individual unruliness is symbolic of the liberties of the British people. The orderly column of grenadiers seen marching northwards in the distance, shows that boisterous Britons will become disciplined defenders of their liberties when the need arises.

Yet despite the crushing of the ’45 and the treaty with France, Hogarth signals to his countrymen to remain vigilant. Beneath the sign of the Adam and Eve tavern, to the left, a different sort of serpent, in the guise of a foppish Frenchman, whispers of an imminent invasion to an ecstatic or demented Jacobite sympathiser. To the right of these conspirators, in the central foreground of the composition, is a young grenadier. According to Rouquet:

he is accompanied, or rather seized and beset by two Women, one of whom is a Ballad-Singer, and the other a News-Hawker; they are both with Child, and claim this Hero as the Father and except this Circumstance they have nothing in common, for their Figures, their Humours, their Characters appear extremely different; they are even of opposite Parties, for the one disposes of Works in favour of the Government, and the other against it.

The woman standing to the left gazes up at him with doleful eyes, hand placed on her swollen belly. Her song sheet, next to a print of the Duke of Cumberland, reads ‘God Save our Noble King’. She is a supporter of the Protestant settlement, embodied by the House of Hanover. The other woman, her face contorted in zealous rage, grasps the grenadier’s arm with her left hand, while raising a rolled-up newspaper with the other. The Jacobite Journal protrudes from her knapsack and a cross is visible on her back. She is a Catholic supporter of the Stuarts. In turn the young grenadier is a representation of the new nation of Great Britain, with the Union flag just behind him. Collectively, this group symbolises the dynastic struggle for the soul of this fledgling state. The Jacobite wields the Remembrancer, an anti-government paper, which serves as a reminder of Britain’s former loyalty to her. The fact that she is about to assault the grenadier with it demonstrates that she is willing to use violence and force to assert her rights over him. The younger woman simply and tearfully indicates to the future and their unborn child.

After the ’45 Prince Charles continued to liaise with Jacobites in Britain and, in the year that Hogarth was completing his March … to Finchley, he made a secret visit to London to discuss a new campaign. Standing near the King’s Head tavern (right), in the shadow of the sign depicting Charles II, is a tall, pale young gentleman who gazes northward, oblivious of the rabble around him. Perhaps this figure is a covert allusion to another Charles Stuart, still determined to return from exile. But he may be too late. Despite the haranguing Jacobite, the young Briton and his comely mistress appear to be moving forward together in step: Britain has already made up its mind.

Jacqueline Riding is author of the forthcoming Jacobites (Bloomsbury, 2015).