‘Vietdamned’ by Clive Webb review

Can Vietdamned: How the World’s Greatest Minds Put America on Trial by Clive Webb rescue Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Sartre’s activism from irrelevance?

In 1966 and 1967 a group of left-wing intellectuals and radical activists, recruited by the nonagenarian philosopher Bertrand Russell, constituted themselves into a self-proclaimed ‘tribunal’ to try the United States of America for its conduct in Vietnam. After holding hearings in Sweden and in Denmark, they convicted the US of waging an illegal war of aggression against Vietnam, of war crimes and, most sensationally, of ‘genocide against the people of Vietnam’.

Then, nothing much happened. The verdicts were welcomed by those who were already convinced of America’s immorality in Indochina and mocked by everyone else, before being forgotten entirely. Even though the American public’s mood eventually soured on the war, the Russell Tribunal had little to do with it. Today, its main legacy lies in the numerous copycat tribunals it has inspired, staffed by cranks, convened in cavernous public buildings, rendering verdicts that, just like the Russell Tribunal’s condemnations of US policy in Vietnam, were never in doubt.

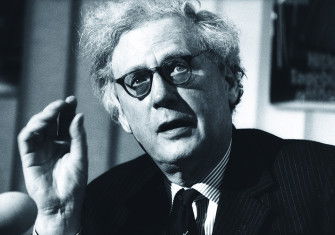

As Clive Webb candidly admits in Vietdamned: How the World’s Greatest Minds Put America on Trial, posterity has been unkind not only to the Tribunal, but to the force behind it. One of Lord Russell’s biographers described his involvement with the venture, as well as his anti-Vietnam War activism more broadly, as ‘a quite colossal vanity’, designed to prove to himself that he still mattered to the world even as his body was failing. In Vietdamned, Webb aims to rescue the Tribunal from the contemptuous footnotes of history, and Russell’s last decade from the embarrassment of his biographers.

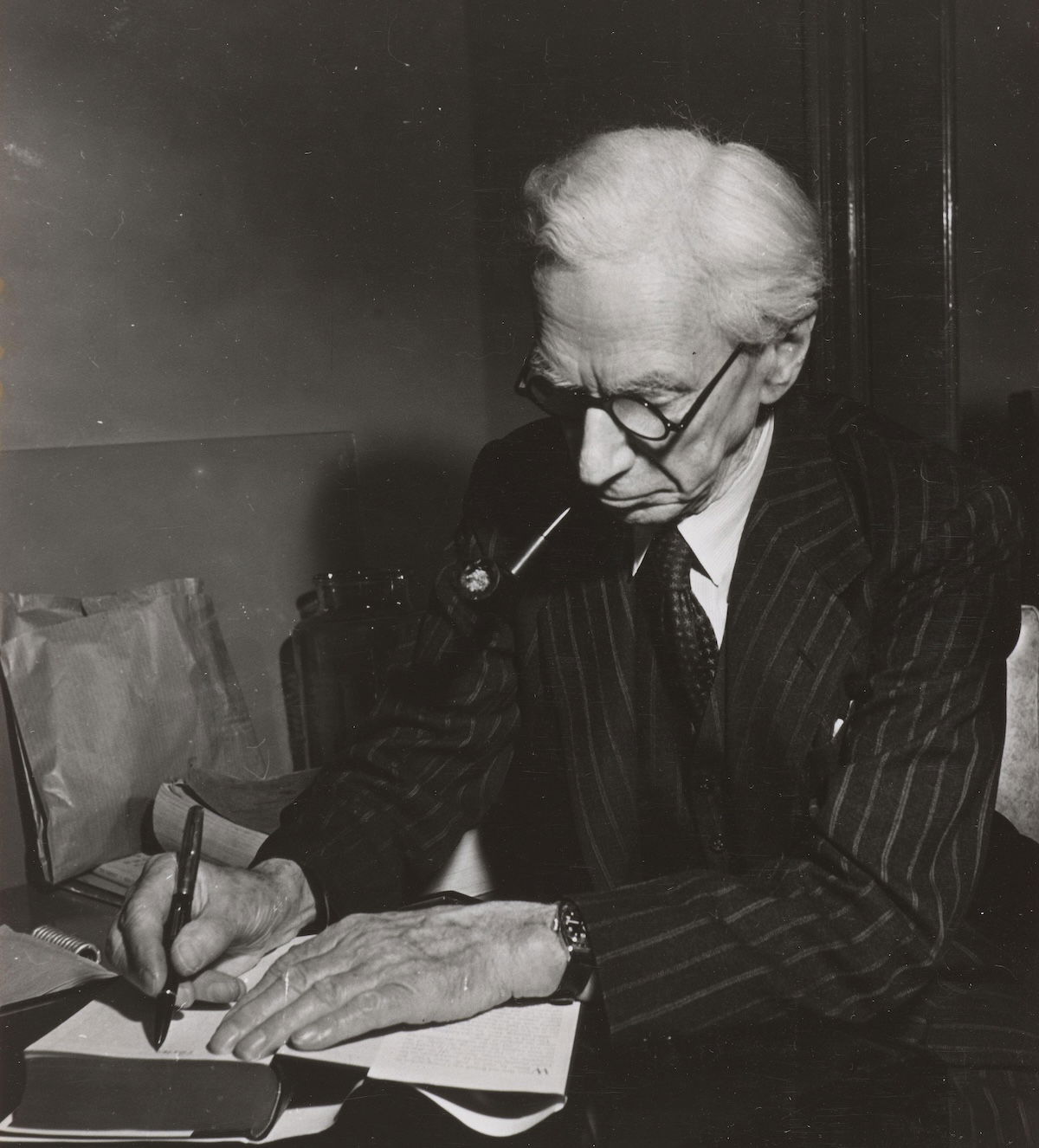

He does not succeed in doing either, but not for lack of trying. Webb, who is in obvious sympathy with the aims of the Tribunal and an admirer of Russell, Victorian aristocrat-turned moral prophet of the nuclear age, puts forward his case for both with skill, backed up by impressive research. In fact, the book is as much a history of the Russell Tribunal as it is a mini-biography of Russell and of the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, the latter of whom dominated the Tribunal’s proceedings (Simone de Beauvoir, billed as the third key protagonist, gets short shrift).

The Tribunal’s two sessions, by contrast, are treated with surprising brevity: the hearings were not very dramatic, and Webb’s narrative of the formal portion of the Tribunal is only rescued from descriptive boredom by stories of clashes between its members, some of whom achieved a level of personal disagreeableness that is impressive even by the standards of intellectuals with revolutionary pretensions. Vladimir Dedijer, the Tribunal’s chairman, seemed to have been particularly dislikeable; and one cannot help but sympathise with Tito’s decision to saddle the Americans with him by driving him into Western exile.

Webb casts both Russell and Sartre in a heroic mode, truth-tellers fighting against a conspiracy between the State Department and the New York Times, who did everything they could to discredit the men and sabotage the proceedings. In some of the book’s most interesting pages, we learn how the American government managed to block the Tribunal from meeting in Paris and London, punished American participants by taking away their passports, and spied on the Tribunal using an unidentified but well-placed mole. If American newspapers seemed to treat the whole thing as a joke, American officialdom was clearly sensitive to its potential impact on world opinion.

Yet Webb is also too honest to manage to make the two men look heroic. Russell emerges as a well-meaning, but fundamentally unworldly figure who was thoroughly ineffective at politics, which is what we expect from our philosophers. Sartre fares much worse: as much as Webb tries to portray him as a centrist who was not rabidly anti-American because he liked jazz, he cannot gloss over Sartre’s defences of the Soviet Union, Maoist China, and Castro’s Cuba, although he does tend to minimise these and other moral stains on Sartre’s record by writing about them as though they were incidental to his great moral stature.

In running their tribunal, both Russell and Sartre were also affected by a naivety that in lesser men would be regarded as straightforward stupidity. Russell told the North Vietnamese that ‘the procedures of the Tribunal must be exact and unimpeachable’ to have any effect on Western opinion, but never paused to consider the fact that appointing a group whose members were often only distinguishable by the shade of communism they espoused would fatally undermine the Tribunal’s legitimacy, such as it was, from the very beginning. Sartre apparently seriously expected the American government to send an emissary to the Tribunal, even though one of its members proclaimed that Lyndon B. Johnson ‘should be boiled alive in napalm’.

By the end of Vietdamned, Webb cannot quite keep up his defence of the Russell Tribunal. In a chapter confusingly titled ‘Vindicated’, he admits that ‘the Tribunal’s narrative of the war was less than entirely reliable’, that ‘its members’ enmity towards US military action blinded them to the barbarities of the North Vietnamese’, and that the Tribunal ‘did not always adhere entirely to the evidence’, particularly when it came to the charge of genocide, a charge which Webb does not even attempt to defend.

In conclusion, Webb writes that although the Russell Tribunal ‘did nothing to bring an end to the war’, and though Russell, Sartre, and their associates ‘did not get everything right’, they ‘set an important precedent for private citizens seeking to hold to account those in power’. Did they really, or did the sorry saga illustrate the impotence of ‘civil society’ and the ineffectiveness of intellectuals seeking political change? Webb has written the best defence of the Russell Tribunal that any fair-minded historian could have managed; and if he fails at rehabilitating its image, it is only because of the unpromising material at his disposal.

-

Vietdamned: How the World’s Greatest Minds Put America on Trial

Clive Webb

Profile, 320pp, £22

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Yuan Yi Zhu is Assistant Professor of International Relations and International Law at Leiden University.