Volume 60 Issue 11 November 2010

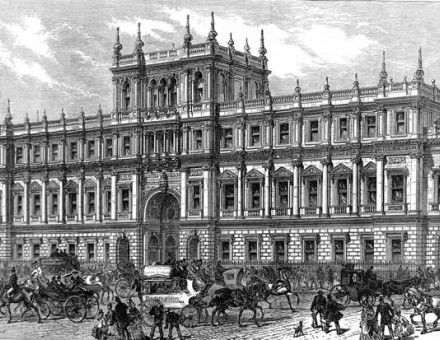

The Royal Society was founded in 1660 to promote scientific research. Through a process of trial and error, this completely new kind of institution slowly discovered how its ambitions might be achieved – often in ways unforeseen by its founders, writes Michael Hunter.

Amanda Vickery’s new series on the 18th-century home is part of an enlightened new strategy from the BBC, writes Paul Lay.

A century after the execution of Dr Crippen for the murder of his wife, Fraser Joyce argues that, in cases hingeing on identification, histories of forensic medicine need to consider the roles played by the public as well as by experts.

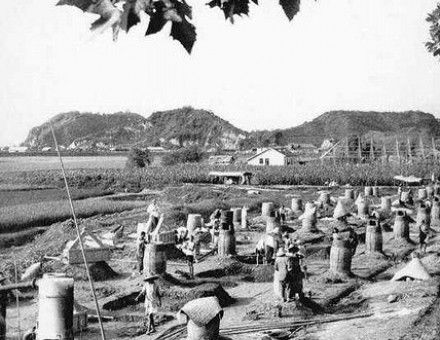

Frank Dikötter looks at how historians’ understanding of China has changed in recent years with the gradual opening of party archives that reveal the full horror of the Maoist era.

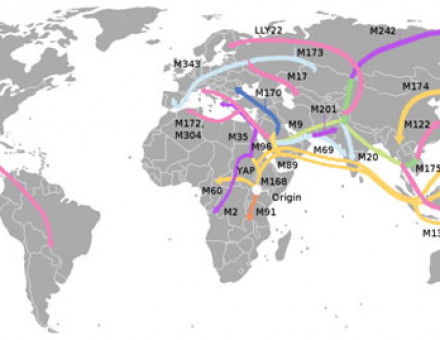

Many reasons have been given for the West’s dominance over the last 500 years. But, Ian Morris argues, its rise to global hegemony was largely due to geographical good fortune.

In 1817, during a period of economic hardship following the war with France, a motley crew of stocking-makers, stonemasons, ironworkers and labourers from a Derbyshire village attempted an uprising against the government. It was swiftly and brutally suppressed. Susan Hibbins tells the story of England’s last attempted revolution.

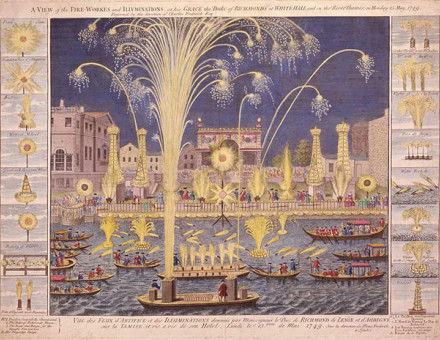

Though they originated in China, it was in the capitals of early modern Europe that fireworks flourished. They united art and science in awesome displays of poltical might, as Simon Werrett explains.

John Fox tells the remarkable story of a dynamic Scottish woman who repeatedly risked her life in order to assist and protect Charles I.