In Good Company: Re-evaluating the legacy of the East India Company

How one company opened an entire sub-continent to economic and political development, with huge ramifications for India, Britain, and the world.

Between 1709 and the mid-19th century the East India Company helped expand international trade, nurtured the City of London and propelled the Industrial Revolution and British prosperity. Yet the Company has come to represent the exploitation and plunder of both the human and economic resources of the Indian subcontinent. Riddled with crony capitalism, the Company suffered an ignominious end, yet its legacy needs re-evaluating.

Between 1709 and the mid-19th century the East India Company helped expand international trade, nurtured the City of London and propelled the Industrial Revolution and British prosperity. Yet the Company has come to represent the exploitation and plunder of both the human and economic resources of the Indian subcontinent. Riddled with crony capitalism, the Company suffered an ignominious end, yet its legacy needs re-evaluating.

Last week at the Legatum Institute, as part of our History of Capitalism series, Professor Huw Bowen of Swansea University delved into the inner workings of the Company. Placing it in the context of its own time, he illustrated how it opened an entire sub-continent to economic and political development, with huge ramifications for India, Britain, and the world.

For many, the East India Company is seen as a rapacious extension of the British state, even at the time it was described as a ‘crew of monsters’ by Horace Walpole, yet this simplistic conclusion is false. The Company’s nature evolved dramatically from 1709 when the newly consolidated ‘United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies’ emerged, to when the company was disbanded in 1874.

Initially few in the Company had territorial ambitions and at first it maintained small outposts in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. It was from these outposts that imports of Indian textiles and Chinese tea made their way to Britain. This trade contributed to the development of the domestic manufacturing sector, while the urban wage-earning class in Britain helped stimulate demand for foreign products. In this respect the Company contributed to the Industrial Revolution – Edmund Burke even suggested that the fortunes of the Company and the country moved in lock-step.

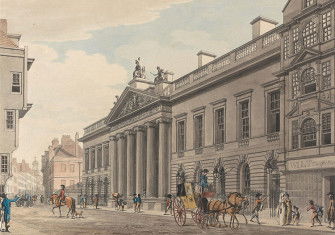

Economically, the development of the company was intertwined with many industries in and around the capital. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the financial sector. For most of the 18th Century the Company dominated London’s blossoming stock market, it was the most attractive stock and as it extended its dominion across the sub-continent the capital it transferred back to Britain deepened the country’s capital markets.

Indeed, it was the extension of direct political control by the Company over swathes of the subcontinent, beginning in the mid-18th century, which transformed it from a trader to a sovereign. As a sovereign the Company came under intense political scrutiny by Parliament and ran up against all the difficulties of colonial administration. In time the pressures of both would increasingly outweigh the benefits the Company was able to extract from its new possessions.

In this respect the Company’s initial success sowed the seeds of its eventual downfall. Not long after the Treaty of Allahabad in 1765, when the Company was granted the right to collect revenues in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, the Crown wished to exert greater control over it. Contemporary opinion was torn over this: some, such as Walpole, saw an out-of-control mercantile leviathan bringing the country into disrepute; others, Bowen notes, saw the Company as ‘an important bulwark against the unwelcome extension of Crown influence into the wider empire’. Better to be ruled by merchants than by corrupt politicians.

Nevertheless the Crown got its way, the Company failed to deliver the surplus revenue it believed it could extract from its dominions and increasingly ran into difficulties. As a result its privileges were cut, most importantly in 1793 and 1802. While the Company had carved out trade with Asia, new political and economic ideas, embodied by Adam Smith’s denunciation of mercantilism, were gaining traction across Britain. As a result it was stripped of its monopoly rights and the trade routes it opened up were used against it by its competitors. By its eventual dissolution in 1874 the Company had ceased to be an important commercial force, and was simply a broken administrative machine.

However, the decline of the Company should not obscure the fact it opened up trade with the Indian sub-continent; the British people and British industry benefitting hugely as a result. For a time the capital it exported back to Britain funded the government and contributed to the international dominance of the City of London. The trade routes it opened up allowed other firms to reap the rewards of free-trade, many of them listing on London’s stock market that the Company had once dominated.

Painting the Company as the incarnation of the worst form of imperialism prevents us from drawing the right lessons from it. The Company’s entrepreneurial energy helped prepare the ground for Britain’s economic success during the Industrial Revolution when trade, capital and adventurism spurred prosperity. Rediscovering these ideals would be no bad thing for Britain today.

Stephen Clarke is a Research Analyst at the Legatum Institute, London.

The Legatum Institute is currently running the History of Capitalism Programme, a series of lectures which explores the origins and development of a movement of thought and endeavour which has transformed the human condition.