Deafness, 'Visible Speech' and Alexander Graham Bell

Bell is most known for the invention of the first patented telephone, but his work on deafness and speech sounds should not be forgotten.

January 25th, 2015 marked the 100-year anniversary of the first transcontinental phone call.

The ceremonial call made in 1915 recreated the moment when Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) and his assistant Thomas A. Watson first discovered their invention worked. In 1876, Bell, working in a room on his own, said to himself, ‘Mr Watson come here, I want to see you’. Watson heard this as though they were stood next to each other and came running. 38 years later, as Bell called him in San Francisco from New York, 3,400 miles apart, Watson replied ‘it would take me a week for me to get to you this time’.

Although Bell is now synonymous with the telephone, his interests were wide-ranging, covering speech and deafness, flight, air conditioning, sheep-breeding and eugenics. By the end of his life he is recorded as having said that both his work with the deaf and his development of a photophone – a device for transmitting sound using light which ultimately proved less efficient than the telephone system – were what he would be remembered for.

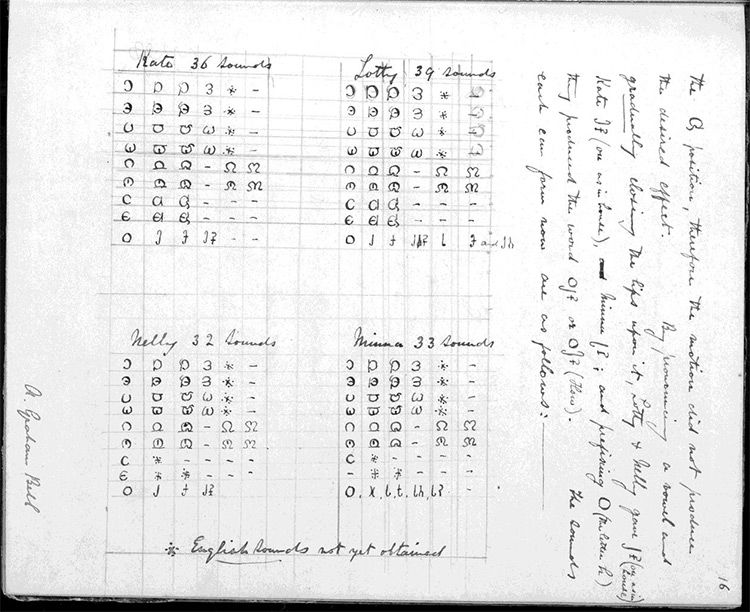

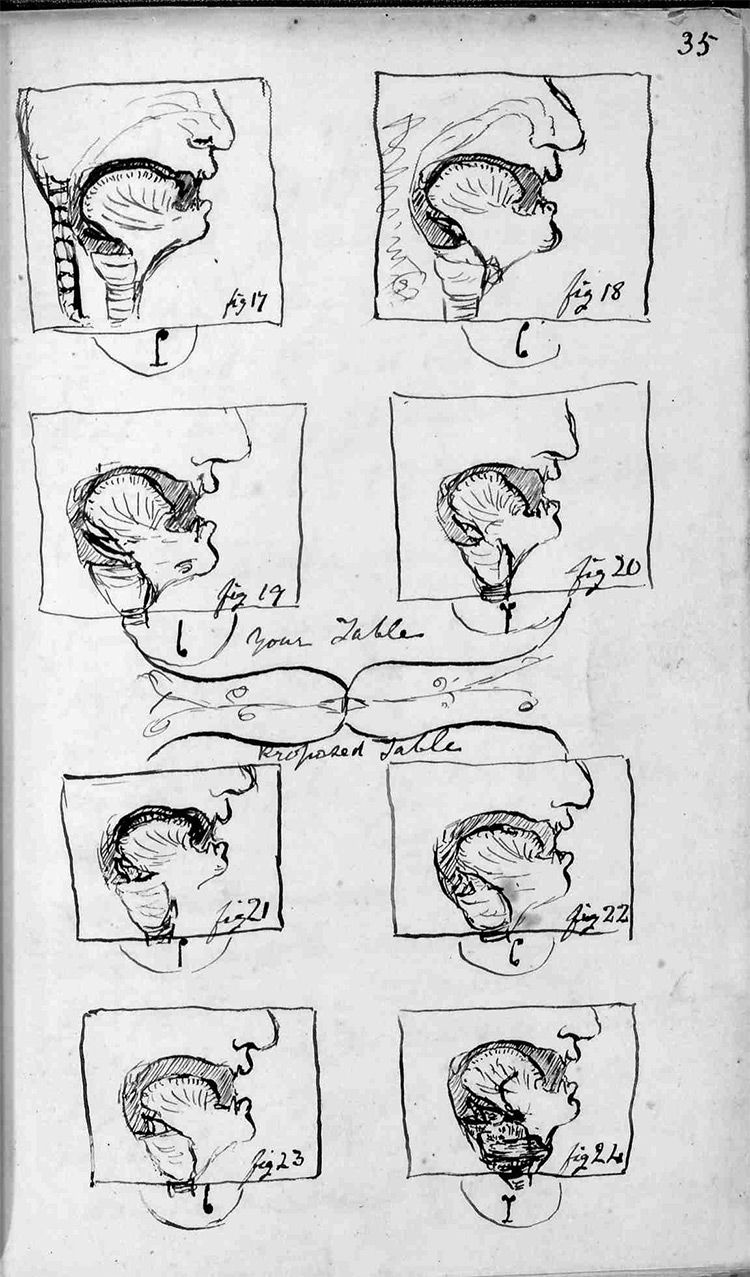

His interest in the telephone came about as a result of his upbringing as the son and grandson of two elocutionists and researchers of deafness and speech. As children he and his brother experimented making sounds by forcing air through the larynx of a dead sheep. Bell’s father, Alexander Melville Bell, developed a phonetic transcription system called Visible Speech in which, much like the modern International Phonetic Alphabet, one shape corresponds to each sound that is found in human speech as well as notations for tone, pitch and suction. This system allowed anyone to accurately pronounce the sounds of a language even if they had never heard it before.

Melville Bell’s Visible Speech proved incredibly popular in helping deaf people learn to speak as by learning to shape their mouths according to the symbols they would produce the right speech sounds. When Alexander Graham Bell joined him in 1868, he toured America demonstrating it and used it to help teach students, ultimately opening his own deaf school. He later married one of his students, Mabel Hubbard. During this time he also began experimenting with the physiology of speech and methods of recording and transmitting sounds.

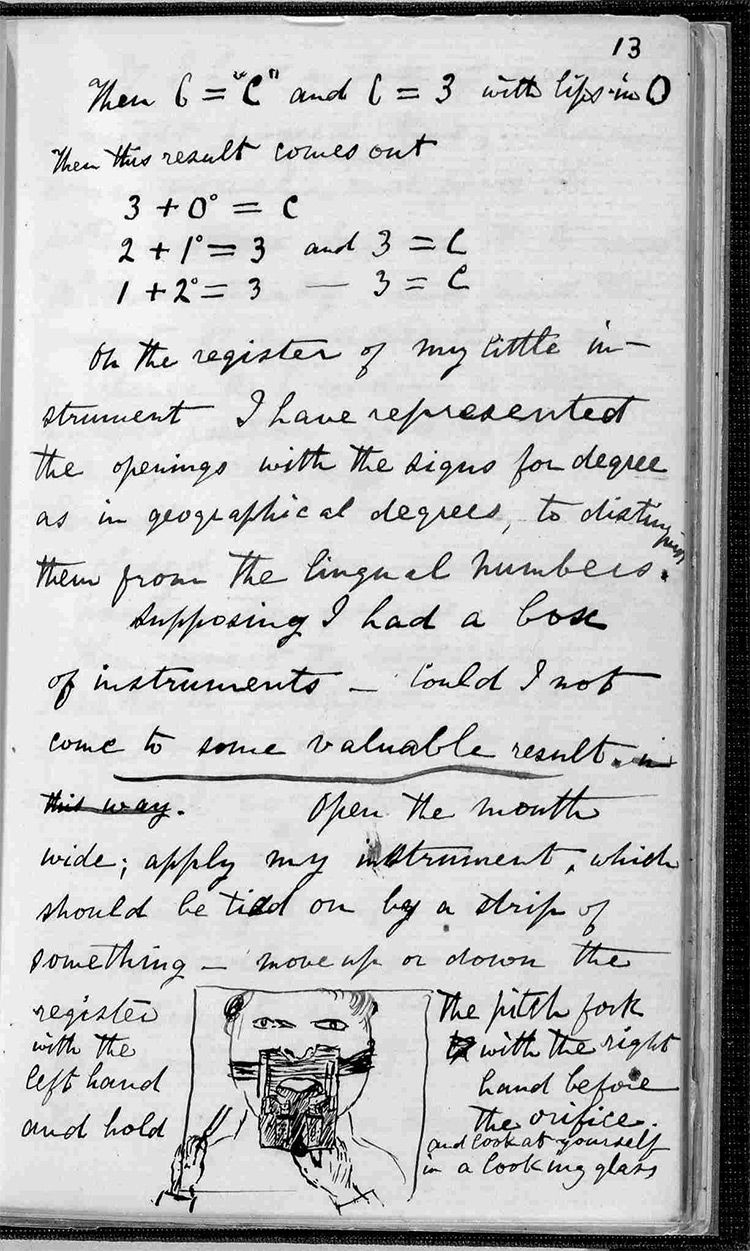

In collaboration with the phonetician A. J. Ellis, Bell worked with an electric tuning fork, or ‘pitchfork’ that could produce speech-like sounds, developing a telegraph system that used tuned reeds to transmit sounds. He later combined this with another invention, a membrane diaphragm based on the human eardrum, which worked as a transmitter. These developments led to, on March 10th 1876, Bell’s first transmitted message to Watson.

Bell also experimented with recording sound. Some of his methods have survived the past century, and recordings of his voice have been recovered by the Smithsonian.

Not all of his work has been as well received as the telephone. Oralism, the belief that deaf people should use lip-reading and speech rather than sign language became widespread following his influential support. However, this overlapped with his research into eugenics and, along with believing that sign language should be avoided, he also believed deaf people should be kept apart to prevent the propagation of hereditary deafness, ‘a deaf variety of the human race’. This meant deaf children were kept apart from each other so they could better integrate in mainstream society. The loss of sign language has been considered by many to be a detriment to the deaf community of America.

In his life Bell achieved many successes and broke new ground in a number of areas. Of these, the telephone is, undeniably, his greatest contribution. He spent most of his later life in Beinn Bhreagh (beautiful mountain), Nova Scotia and, following his death in 1922, was buried at the top of the hill there. To mark his passing, all telephone communications in America ceased for one minute.

Kate Wiles is Contributing Editor at History Today.