‘Rot: A History of the Irish Famine’ by Padraic X. Scanlan review

Padraic X. Scanlan levels familiar charges against British colonialism and capitalism in Rot: A History of the Irish Famine. Is there more to the story?

Writing from the safety of exile in eastern Tennessee, in the late 1850s the fiery Irish nationalist John Mitchel published a series of articles in his proslavery newspaper the Southern Citizen. In 1861 those articles reappeared as The Last Conquest of Ireland (Perhaps), a vociferous condemnation of British policy during the Great Famine of 1845-52, and inspiration to nationalists for generations to come. In his oft-quoted, emotive conclusion Mitchel wrote how ‘[a] million and half of men, women, and children were carefully, prudently, and peacefully slain by the English government. They died of hunger in the midst of abundance which their own hands created’. In Mitchel’s depiction, the Famine was the result of the British government’s singular obsession with the laws of ‘political economy’ – an adherence to economic principles that ideologically blinkered officials from providing the Irish with aid to stop them starving, instead trusting in Providence and markets to determine Ireland’s future.

It is not hard to see the imprint of Mitchel’s argument in Padraic X. Scanlan’s Rot: A History of the Irish Famine, even if it is largely unacknowledged by the author. Scanlan’s lucidly written and well-paced book revolves around a straightforward claim: that the Famine was the result of the interlocking ideological systems of British colonialism and British capitalism. These systems had, over a few centuries, structured the Irish economy in such an exploitative way as to render its society acutely vulnerable to the dual shock of a blight on its main food source – potatoes – and the vicissitudes of a global market that exposed the population to extreme poverty. While Irish agriculture appeared backwards, Scanlan suggests that those forced to survive on a single product did so because of Britain’s industrial cities’ voracious appetite for Irish grain and livestock. ‘The Irish way of life looked ancient’, Scanlan writes, ‘but it was heartbreakingly, almost quintessentially, modern.’

Scanlan is not wrong. Historians of Ireland have long recognised the importance of British capitalism in structuring the uneven political and economic relationship between the islands, as well as the legacy of land confiscations in determining the social dynamics of the Irish countryside. Rot builds on this literature, and the early chapters focus, in particular, on how the exploitation of Irish peasants paired with popular representations of the Irish as lazy and uncivilised, living in a primitive state of existence. These stereotypes found their fullest expression in one Times article as ‘potatophagi’ – the potato eating people. As Scanlan notes, potato dependence was an inherent feature of the entrenchment of the Irish economy into the British capitalist system after the Union of 1800. Yet for many Britons potato cultivation was ‘evidence of a bloody-minded refusal of the benefits of civilisation’ as it did not require the ‘extensive division of labour to grow, harvest, or prepare’. In one of the book’s more provocative passages, the author questions the veracity of the statistic that the average Irish male labourer ate 14 pounds of potatoes a day, and suggests the statistic’s outlandishness was a ‘useful symbolic quantity’ to show Irish potato dependence and to reinforce British superiority over ‘an inferior people … exquisitely adapted to an inferior food’.

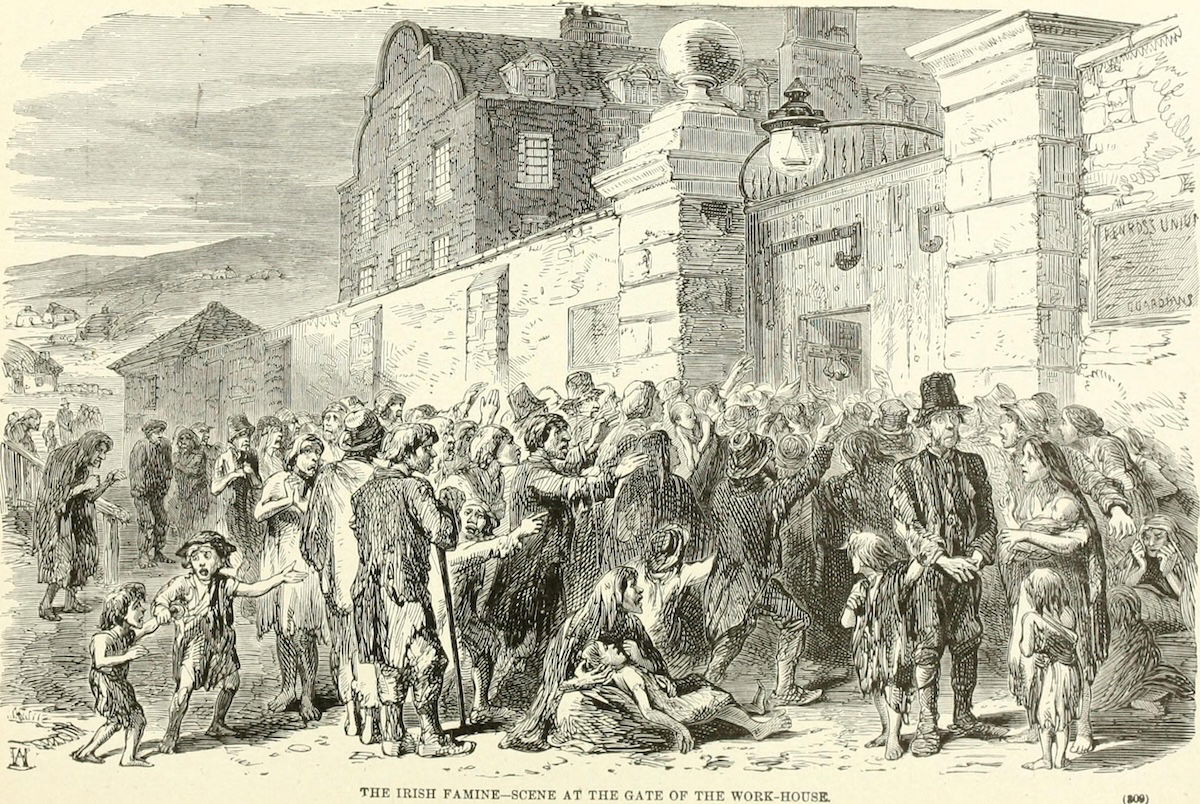

The later chapters of the book shift to British policy during the Famine itself, which built on stereotypes and perceptions of Irish economic backwardness, as well as commitment to political economic orthodoxies. Scanlan notes that British officials – Whigs, Conservatives, and Liberals – all approached relief policies singing from the same hymn sheet, where ‘early Victorian political imagination … could only see a solution to famine that depended on market principles and the disciplinary power of supply and demand’. Officials feared so-called ‘eleemosynary aid’ – ‘giving relief without labour in exchange’ – because they believed charity did not possess the power to solve Irish problems; the only thing that could do that was the ‘civilising power of the market’. Thus the importation of £100,000 worth of American corn by Robert Peel’s government was, in Scanlan’s telling, a risk-free endeavour demonstrating the power of free trade by strengthening transatlantic connections, conditioning the Irish to abandon potatoes for grain, and, thereby, opening ‘new markets for British grain’. In short, Scanlan argues: ‘No one in Parliament had much to lose.’ This is a radical reading that veers from the generally accepted view that Peel’s decisive action in importing American grain (entering the UK tariff free), along with the implementation of a public-works programme, helped stem the disastrous effects of the initial potato crop failure in late 1845. Of course, officials did not know that the blight would return in 1846.

The singularly focused argument that propels Scanlan’s account, and the author’s gift to marshal an array of material to colour his story, means this work will be widely read by the general public – no bad thing. However, the simplicity of argument comes at a cost, eroding much of the complexity and contradictions of the Famine’s occurrence. For example, the Poor Law that became Irish law in 1838 – which by locating relief in the dreaded workhouse did so much to determine the outcome of the Famine – was the near mirror image of the English Poor Law of 1834, suggesting a continuity in policy between the islands. This surely implies that some of the rhetoric of elites condemning insolence, moral failure, and a lack of industriousness was not confined solely to the Irish poor but also extended to the English poor, too. Similarly, while the author acknowledges Ireland’s place in the Union he suggests that the logics of colonialism dominated the islands’ relationship. In the process, his account too often renders the Irish passive victims of British perfidy rather than complex historical actors in their own right. As such, the book retells an old narrative that historians have taken nearly two generations to build upon, unsettle, and complicate.

-

Rot: A History of the Irish Famine

Padraic X. Scanlan

Robinson, 352pp, £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Jay Roszman is a lecturer in 19th-century Irish history at University College Cork and is the author of Outrage in the Age of Reform (Cambridge University Press, 2022)