Britain: apart from or a part of Europe?

The ‘Historians for Britain’ campaign believes that Britain’s unique history sets it apart from the rest of Europe.

Why ‘Historians for Britain’? In many ways the organisation that I and several colleagues have been setting up over the last year could equally well have been entitled ‘Historians for Europe’, for we are not hostile to Europe and we believe that in an ideal world Britain would remain within a radically reformed European Union. We are a group of historians, both inside and outside the universities, who believe that a historical perspective on Britain’s relationship with Europe urgently needs to be supplied at a time when debate about that relationship has become not just lively but heated. As an offshoot of the pressure group Business for Britain, our view is that the British public does need to be consulted about Britain’s membership of the European Union. At the same time, a referendum held tomorrow would leave no chance for the renegotiation of Britain’s position in the EU and an opportunity for that is vital. More than that: renegotiation has to include a commitment by the EU itself to reform its ways and, at the very least, to leave those countries that do not seek to be part of a ‘United States of Europe’ free to rely upon their own sovereign institutions without interference.

Why ‘Historians for Britain’? In many ways the organisation that I and several colleagues have been setting up over the last year could equally well have been entitled ‘Historians for Europe’, for we are not hostile to Europe and we believe that in an ideal world Britain would remain within a radically reformed European Union. We are a group of historians, both inside and outside the universities, who believe that a historical perspective on Britain’s relationship with Europe urgently needs to be supplied at a time when debate about that relationship has become not just lively but heated. As an offshoot of the pressure group Business for Britain, our view is that the British public does need to be consulted about Britain’s membership of the European Union. At the same time, a referendum held tomorrow would leave no chance for the renegotiation of Britain’s position in the EU and an opportunity for that is vital. More than that: renegotiation has to include a commitment by the EU itself to reform its ways and, at the very least, to leave those countries that do not seek to be part of a ‘United States of Europe’ free to rely upon their own sovereign institutions without interference.

That might sound like a political manifesto rather than a series of historical arguments. Yet we hold political views that span the spectrum from the right to the left. We aim to show how the United Kingdom has developed in a distinctive way by comparison with its continental neighbours. This has resulted in the creation of a different legal system based on precedent, rather than Roman law or Napoleonic codes; the British Parliament embodies principles of political conduct that have their roots in the 13th century or earlier; ancient institutions, such as the monarchy and several universities, have survived (and evolved) with scarcely a break over many centuries. This degree of continuity is unparalleled in continental Europe. To some extent you can find it in parts of Spain; but even there, where parliamentary assembles go back well into the Middle Ages, radical constitutional change and civil war have broken many continuities. You cannot find it in France after the Revolution and the Napoleonic era, while Germany and Italy are 19th-century creations, whose political systems were almost entirely reconstructed after 1945. Portugal apart, national boundaries have fluctuated, often wildly, over the centuries; and even Britain has contracted, with the departure of most of Ireland. But – allowing for occasional coups d’état by Henry VII and William of Orange – Britain has not been torn apart by invasion since 1066. Nor has its public favoured the intense nationalism that has consumed many European countries, even allowing for the independence campaign in Scotland. Fascism and antisemitism never struck deep roots here, nor did Communism (except as a silly fad among student politicians). The British political temper has been milder than that in the larger European countries.

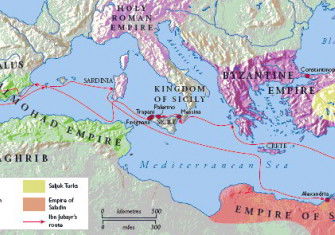

Alongside these differences there is a long history of British engagement with Europe; not just English engagement, but also Scottish (the ‘auld alliance’ with France, most notably). ‘Fog in Channel, Continent Isolated’, the famous newspaper headline, does not represent the real nature of Britain’s involvement in Europe, whether one thinks of the wool trade with Flanders that was such a source of wealth in the Middle Ages, or the English conquests that reached as far as Gascony, the ‘longest alliance’ between England and Portugal or, indeed, in more recent times, the British presence in the Mediterranean that at various points brought not just Gibraltar but Minorca, Corsica, Malta, Corfu and Cyprus under the British flag. British and French guarantees to Poland were honoured in 1939, with the result that we found ourselves in a war to the death with Germany.

One way to describe this relationship would be to say that the United Kingdom has always been a partner of Europe without being a full participant in it. After all, until the second half of the 20th century, Britain still ruled over vast tracts of the globe very far from Europe. Becoming European might be seen as a reaction to ceasing to be imperial, or at least to the loosening of ties with the growing Commonwealth. But that is to over-simplify a complex recent history: in 1973 the United Kingdom joined a Common Market and there are many who would have preferred the founders of what is now the European Union to have forgotten their dreams of ‘ever-greater union’ and to have concentrated on making that economic association work better.

Historians for Britain aims to facilitate that debate. How one votes in a referendum should be influenced by what sort of new offer is on the table following renegotiation of Britain’s position within the EU. That offer has to reflect the distinctive character of the United Kingdom, rooted in its largely uninterrupted history since the Middle Ages.

Read a response to this article: Fog in Channel, Historians Isolated

David Abulafia is Professor of Mediterranean History at the University of Cambridge and Chairman of Historians for Britain.