‘Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife’ and ‘God’s Own Gentlewoman’ review

Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The Extraordinary Lives of Medieval Women and God’s Own Gentlewoman bring the real world of medieval women out of the margins.

Fed up with reading misogynistic texts about the nature of women, written by men, Christine de Pizan decided she could do better. The Book of the City of Ladies, completed around 1405, was the result, becoming her most famous work. The widowed Christine went on to make a living from her writing, supporting her family as the first professional female author in Europe.

Margery Kempe gave up her duties as a wife and mother in order to devote herself to God and to take pilgrimages both in England and abroad; upon her return she dictated her memoirs, authoring, around 1430, the first surviving English autobiography. One of the people Margery met on her travels was the mystic and anchoress Julian of Norwich, who had locked herself away from the world to concentrate on spiritual matters and write her Revelations of Divine Love, a work still widely quoted today (‘all shall be well and all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well’). And some two centuries before any of these three women were born, the poet Marie de France left her homeland for England, there to compose subversive tales featuring resourceful heroines who were very different from the heroes of the prevailing male-dominated literature.

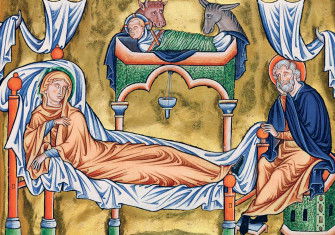

These women are the titular subjects of Hetta Howes’ lively and enjoyable Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The Extraordinary Lives of Medieval Women, which uses their careers and writings as a springboard for a wide-ranging discussion of women’s lives in the Middle Ages. This is not a simple group biography, but rather an examination, in a series of thematic chapters, of topics such as experiences of childbirth, being a wife, travelling and earning a living, religious life and the power of female friendship. The result is illuminating, although the stylistically jarring conclusion, speculating on what the four subjects would make of the modern world and listing the many disadvantages women still face, is a disappointing end to a book that otherwise evokes the spirit of the period so well; modern attitudes on what constitutes ‘legitimate rape’ do not tell us much about the Middle Ages.

Two aspects of the work are particularly thought-provoking and illustrate Howes’ broader argument about medieval women’s voices. The first is that direct quotes from the writings of her four subjects are equalled, if not surpassed, in number by those of their male contemporaries. As Howes notes, readers of medieval texts (both then and now) are vastly more likely to find themselves reading about women’s experiences in works by a male author, because ‘women were not encouraged to write for public consumption’ and the prevailing attitude was that women ‘were better off staying at home’. Despite the efforts of Marie, Margery, Christine and Julian, the appearance of a woman in public intellectual life was rare, and modern readers have to make an effort to find these female voices amid the cacophony of male ones trying to drown them out. Howes’ subjects were fortunate in that they were of a high enough class to transgress some contemporary expectations, but still they had to be extraordinary to be heard at all.

A second surprise is that we do not find out all that much about the personal lives of the four women themselves, and this, again, is illustrative of contemporary attitudes: medieval women were not meant to be public creatures. Marie ‘tells old stories in a new language, but nothing of herself’; Julian removed almost every personal trace from her work; Christine ‘only ever tells us what she wanted us to know’ as she was busy ‘building a brand’. It is only Margery, writing an autobiography, who reveals something of herself. As such, she comes across as the most fully human and complex of the book’s subjects. Howes’ affectionate portrayal allows the reader to visualise Margery clearly, irritating her fellow pilgrims with her constant exhortations of faith and uncontrollable weeping, and annoying the Church even more with her stubbornness. She was a spiritual woman living in the secular world, rejecting the approved binaries of wife and mother or cloistered nun. This made her dangerous.

The women featured in Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife have in common that they were exceptions to the normal rules governing women in public life – and that they were writing for posterity. This puts them in contrast with another late medieval woman, who makes a cameo appearance in Howes’ book but who is the central subject of Diane Watt’s God’s Own Gentlewoman. Margaret Paston married into a family of Norfolk gentry around 1440. A private individual writing letters in a personal capacity, many of which are among those of the surviving Paston corpus, it is precisely because she was not writing for a public audience that her letters tell us so much about her and her era.

In some respects Margaret was very much the epitome of her sex, class and era: she married young, was the mother of seven surviving children and ran the family estates during the frequent lengthy absences of her husband, a lawyer, in London. Her letters span the course of many years, so we get to know her personally as bride, wife, mother and, eventually, widow. Watt is far too pragmatic to claim to have discovered the ‘real’ woman behind the pen. Rather, she lets the evidence speak for itself and, like Howes, uses her subject’s life and writings as the basis for an examination of medieval women’s experiences in a wider context.

Watt presents a carefully selected set of letters from Margaret’s collection, written between the 1440s and the 1480s. They enlighten the reader on subjects of national, local and personal interest: the Wars of the Roses, religious practices, hawking, legal disputes, clandestine marriages, the progress of Margaret’s latest pregnancy and the efficacy (or not) of treacle as a treatment for bubonic plague. The greatest danger for this book was always going to be that Watt’s abundant scholarly expertise would overwhelm a narrative aimed at a general audience, but happily this is not the case. The reading experience is pleasingly like watching a play: Watt steps forward to explain the context and provide a framing device before retreating to the wings to leave Margaret in the limelight as she speaks in her own vibrant voice. The book is, incidentally, a cracking tourist guide to Norfolk.

In a world where the ‘perfect’ woman was meek and mild, silent and supportive, and expected to be little more than a helpmeet, all five of these women broke the mould. Or did they? The Church, and the society in which they lived, might have told women that they were weak vessels who were inferior to men, but life in practice was very different from that in theory. Women did work, managing estates, businesses and families – and they were, moreover, expected to be proficient at all these things.

Medieval women were multi-taskers par excellence, and Howes and Watt, working with different collections of source material, illustrate this admirably. Their subjects lived in the real world, not the one imagined by male writers. They had to juggle many competing demands: Christine wrote while bringing up her children as a single mother; Julian endeavoured to commune silently with God and write about her mystical revelations while also dealing with the stream of visitors who wanted her advice.

The final word on the medieval female experience – or, at least, that of the gentry class – can safely be left to Margaret Paston herself. In her most famous letter she first entreats her husband ‘to get some crossbows and windlasses to bend them with, and bolts’ along with ‘two or three short poleaxes to defend the doors’, because their manor is under armed attack and she has been left to defend it in his absence. But she has other matters on her mind too, ending with shopping requests for almonds and sugar for the household, and fabric to make new clothes for their growing children. Could there be a better example of the astonishing range of women’s responsibilities in the Middle Ages?

-

Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The Extraordinary Lives of Medieval Women

Hetta Howes

Bloomsbury, 320pp, £22

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link) -

God’s Own Gentlewoman: The Life of Margaret Paston

Diane Watt

Icon, 288pp, £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Catherine Hanley’s latest book is 1217: The Battles That Saved England (Osprey, 2024).