Noisy Neighbour

Exploring St Paul’s Cathedral’s secular churchyard.

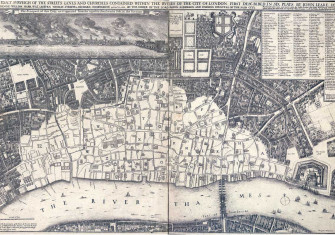

St Paul’s Cathedral is London’s premier church. Dedicated to the City’s patron saint, from its elevated position on Ludgate Hill it has been the focal point of the City of London since its foundation in the early seventh century. Unlike many of London’s religious houses, it survived the Reformation, the Civil Wars and, famously, the Blitz, and unlike dozens of London’s parish churches it came back from the devastation of the Great Fire of 1666: a phoenix and the word ‘Resurgam’ appropriately form part of its western front. Once the largest Norman cathedral in northern Europe, after Wren’s controversial baroque post-fire redesign it became a totem of wartime London’s defiance. It also experienced phases of decline and neglect; funds were sought in the early 17th century to undertake essential renovations (the steeple was destroyed by a lightning strike in 1561 and never rebuilt) and contemporaries testified to how its splendour became diminished by the encroachment of commercial premises during the Victorian period.

Margaret Willes’ fine study is not, however, about the cathedral itself, about which, as she says in her introduction, ‘books aplenty’ have been published. Rather, it is a wide-ranging account of its immediate environs, chiefly, but not exclusively, its churchyard, from its Saxon foundation to the Occupy protests of 2011-12. Among the topics covered in between is the absolute centrality of the area to the London book trade across many centuries.

Willes shows how, alongside their devotional uses, the cathedral and its churchyard have had important secular, economic and cultural meanings for generations of Londoners and visitors alike. She focuses on what she calls ‘the idea of the Churchyard’, a notion that implies that this was a space put to an unusual variety of different uses. The precincts of St Paul’s, Willes argues, had always been unlike those of other cathedrals, let alone those of rural parishes, being distinctively urban and uniquely associated with diverse practices.

St Paul’s churchyard was indeed a heterogeneous locale in the context of a city where open space was at a premium. Such was the extent of the secular use of this area, Willes contends, that ‘the Churchyard invaded the cathedral’, bringing its economic and social dynamism into the sacred space. An example is Thomas Dekker’s satirical treatment in The Gull’s Hornbook (1609) of ‘Paul’s walk’, the cathedral’s central aisle, which he depicts as a place to show off one’s new cloak or seek sanctuary from one’s creditors. Indeed, as Willes shows, after the Great Fire the churchyard – directly on the route from the City’s major thoroughfare, Cheapside, to its western access point from Fleet Street – became a shopping destination.

In the Shadow of St Paul’s Cathedral is nicely attuned to the consequences of this overlapping of the worldly with the religious. Far from being a sea of calm and piety, the churchyard could be as cacophonous as anywhere else in the City. Willes describes how as far back as 1345 the ‘scurrility, clamour and nuisance’ of a local market was complained of for interfering with divine services; such protestations continued for centuries, as did debates about the layout of the churchyard. The precinct could also serve as what Willes aptly calls a ‘theatre of opposition’. Here, power and resistance alike were played out; the sermons regularly delivered at Paul’s Cross often engaged directly with political concerns and perennial religious schism. The churchyard likewise witnessed the staging of dynastic upheaval as well as the celebration of secular authority, through the reception of monarchs and mayors from the time of King John onwards. As with other places of topographical prominence in the City, such as Cheapside, it could also become a site of public punishment (including the execution of some of the 1605 Gunpowder Plot conspirators) and the burning of heretical books.

Willes pays due attention to the cultural significance of the environs of the cathedral. Home in the 16th century to a troupe of child actors called ‘Paul’s Boys’, who performed in their own space within the cathedral boundary as well as at court and to civic dignitaries in a number of grand livery halls, the churchyard played a crucial role in fostering and disseminating literary culture. It was not only the home of numerous printers and booksellers from the time of Caxton and Wynken de Worde right through to the 19th century, but it was also the place where John Donne’s famed sermons were first heard. Willes provides illuminating examples of how St Paul’s itself became the subject, as well as the setting, of literary and satirical works, testament to its importance to Londoners’ lives. The sale of music and instruments and the presence of novel trades such as cabinet-making, took the churchyard in new directions in the 18th century, although Willes adeptly shows the continuities with previous periods. Drawing on an extraordinary array of contemporary documents, she highlights the resilience and adaptability of this space and its inhabitants right up to the point when it changed utterly, once the bombs fell in 1940.

Willes wears her scholarship fairly lightly and has written a sure-footed and readable account, packed full of fascinating detail. At the same time, In the Shadow of St Paul’s does an excellent job of digesting a large body of research, lucidly summarised in the introduction. The book will generate interest in and a fuller understanding of St Paul’s beyond its familiar status as a staging post on the London tourist trail.

In the Shadow of St Paul’s Cathedral: The Churchyard that Shaped London

Margaret Willes

Yale University Press 320pp £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Tracey Hill is Professor of Early Modern Literature and Culture at Bath Spa University and the author of Pageantry and Power: a Cultural History of the Early Modern Lord Mayor’s Show, 1585-1639 (Manchester University Press, 2010).

![‘Scientific Researches! New Discoveries in Pneumaticks! [sic] or an Experimental Lecture on the Powers of Air, May 23, 1802’, by James Gillray. Minneapolis Institute of Art. Public Domain.](/sites/default/files/styles/teaser_list/public/2025-03/lecture_history_today_0.jpg?itok=mHN_obPV)