‘Massacre in the Clouds’ by Kim A. Wagner review

In Massacre in the Clouds: An American Atrocity and the Erasure of History, Kim A. Wagner offers a blow-by-blow account of Bud Dajo. But is the devil truly in the detail?

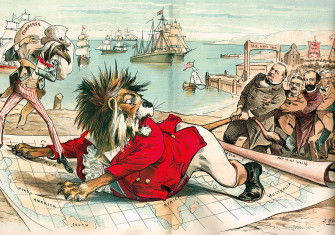

At the turn of the 20th century, like so many otherwise clever men of his class, the English explorer Arnold Henry Savage Landor succumbed to the siren of race science. Fancying himself as something of a craniometrist, he pronounced the Muslim Moros of the Philippines morons, with their ‘flattened skulls’ and ‘stumpy, repulsive-looking hands, typical of criminals’. It was a perspective his American colleagues shared. Still, after colonising the Philippines in 1898, they had to tolerate the Moro chiefs of the south, if only on sufferance. The Spaniards had never succeeded in displacing the Moros, accepting a power-sharing arrangement. The Americans inherited this relationship.

This was the first time Americans were having to deal with Muslims on something resembling an equal footing, and it came with its attendant challenges. The racists had to swallow their pride, but so did the liberals: the Moros practised slavery. The Americans appealed to the Sultan of Sulu’s better instincts, but to no avail. ‘Slaves are a part of our property’, came the reply. All the same, the Philippines’ American governors made a serious attempt at ending the sale and murder of slaves in the early 1900s, much to the consternation of the Moro chiefs, one of whom asked: ‘If a Moro chief cannot kill a slave, what can he do? Can he drink water? Can he breathe air? Has he any rights at all?’

Then there were the rights the Americans had given themselves but didn’t want to extend to the Moros. Like the former, the latter were overfond of weapons, in their case swords and blades. But the benighted natives, the colonisers felt, weren’t enlightened enough for a Second Amendment of their own.

Things came to a head in 1906, as the Americans set about trying to dispossess the Moros of their swords and slaves. The final straw was the introduction of a poll tax. And so a thousand Moros voted with their feet and took off to Bud Dajo, the crater of an extinct volcano in the Sulu Archipelago. There they eked out an existence, subsisting on water from the crater, sweet potatoes and tapioca cultivated around it, and mangoes that grew in the foothills. Escaping easily controllable lowlands, where conscription and taxation are a perennial threat, for the stateless simplicity of uplands is something Asians have done for over two millennia, as James C. Scott argued in The Art of Not Being Governed.

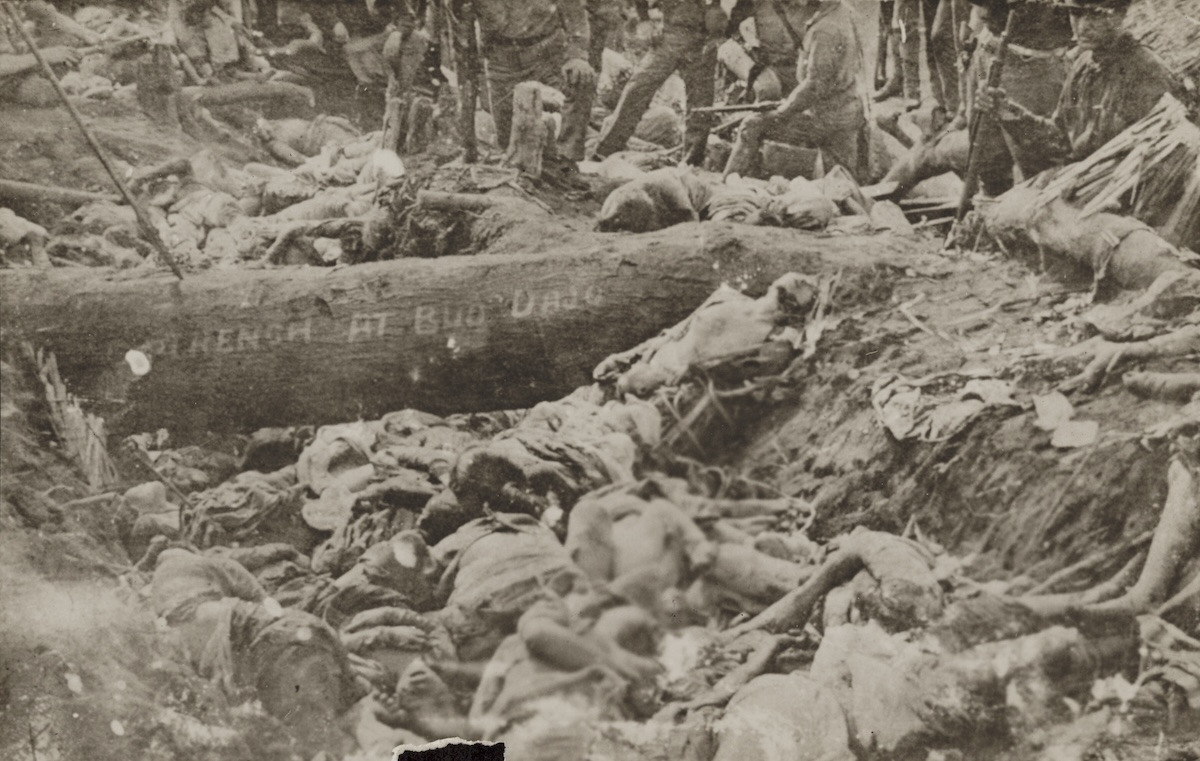

At this, Leonard Wood, American governor of Moro Province, decided to put the Moros in their place: ‘I think one clean-cut lesson will be quite sufficient.’ Kim Wagner’s book is the story of the massacre that followed. Plans were made to torch the crater to smoke the Moros out; one American described them as ‘human hornets’. In the end they settled on artillery and machine guns. Another US soldier likened the punitive expedition to a ‘pigeon shoot’. The aim was to exterminate. ‘At no point during the assault on Bud Dajo was the possibility of taking prisoners even mentioned’, Wagner writes.

In all, some thousand Moros were killed, one of the worst massacres in modern history. The following day Wood imposed a telegram blackout, even as soldiers showcased Moro skulls on the streets of Jolo. Word nevertheless got around, and the Democrats and the Washington Post criticised Wood, who had to defend himself from the charge of ‘wanton slaughter’. Women and children were killed, Wood conceded, but only because the Moro men had used them as human shields.

The lie was accepted at face value, and in the weeks that followed the Republican president, party and press closed ranks, endorsing Wood’s handling at Bud Dajo. It was a cruel necessity and Wood had managed the whole affair as ‘humanely’ as possible, ran the official line. Wood himself emerged from the affair with no damage to his career, coming within a whisker of winning the Republican presidential nomination in 1920. In retirement he spent his days inveighing against mixed marriages.

Wagner is right to suggest that this is a story that needs to be told again and again, but I wonder if he is the right person to tell it. This is an episode that would have made for an interesting chapter in a broader study on American imperialism. Wagner, however, dishes up an excruciatingly detailed hour-by-hour account. His book, he says, is a ‘100,000-word caption’ to the only surviving photo of the massacre, and there lies the rub. In lieu of sustained interpretation, we have reams on ‘old breech-loading .45-70 Springfield Cavalry carbines’ and ‘Winchester Model M1897 12-gauge pump-action shotguns’. Only war specialists will welcome his editorial decision to regurgitate his entire archive, rather than condense his material in intelligible paraphrases. What’s more, in his haste to indict the US and its historians, he makes some questionable claims. In Wood’s hankering for a ‘clean-cut lesson’, for instance, Wagner sees the hand of Anglo-American imperial thinking, as if the policy of schrecklichkeit – exemplary atrocities – were a modern invention. In truth, all empires from Chinggis Khan onward have engaged in the same practice.

Wagner’s conceit, that he alone is offering the unvarnished truth about empire, is likely to grate on readers. Even a historian like Daniel Immerwahr, who has done more than most to call attention to the ‘Greater United States’ built on violence, is accused of defending America’s empire – of using Bud Dajo as a ‘foil’ to wax eloquent on the ‘heroic and humane’ governance of Wood’s successor, John J. Pershing. Immerwahr does indeed praise Pershing for befriending Moro chiefs and avoiding conflict in How to Hide an Empire, but Wagner must have forgotten the part where he upbraids the governor for killing 500 Moros in the Bud Bagsak massacre of 1913. It is precisely such nuances that distinguish mature histories from finger-wagging narratives. Wagner can chronicle every atrocity he likes, one book-length study at a time, but I suspect that isn’t going to get him any closer to an unalloyed ‘truth’ about empire.

-

Massacre in the Clouds: An American Atrocity and the Erasure of History

Kim A. Wagner

PublicAffairs, 400pp, £28

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Pratinav Anil teaches at St Edmund Hall, Oxford.