Losing the Plot

One of the most notorious conspiracies in British history.

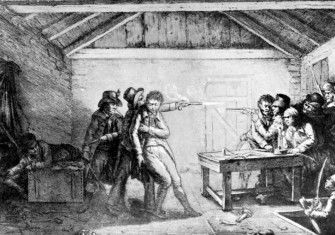

As Vic Gatrell writes, the Cato Street Conspiracy is ‘underdog history at its purest’. On the evening of 23 February 1820 around 25 men gathered in the hayloft of a stable on Cato Street, off Edgware Road in London. Led by Arthur Thistlewood, they had met to formulate a plan to murder the prime minister, Lord Liverpool, and his cabinet, some of whom were dining in Grosvenor Square. Former soldiers John Harrison and Robert Adams were to kill the ministers before the butcher James Ings would ‘cut off every head that was in the room, and the heads of Lords Castlereagh and Sidmouth he would bring away in a bag’.

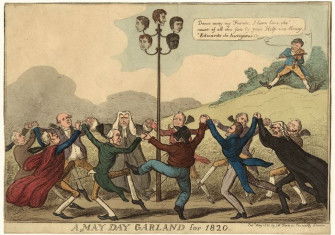

The plot failed. Another conspirator, George Edwards, had turned informant and the Bow Street constables arrived at the stable, followed by the military. A gun battle ensued as the men either resisted arrest or fled. Thistlewood, Ings and three others were arrested, convicted of treason and executed at Newgate on 1 May 1820; five others were transported to New South Wales. Despite its failure, the Cato Street conspiracy has long been a source of fascination for scholars of Regency Britain. Why did it not succeed? And why did Britain not undergo a revolution during this era of tumultuous political upheaval?

The conspirators were drawn from the ‘radical underworld’, followers of the land nationalisation campaigner Thomas Spence, who had died in 1814. Calling themselves ‘Spencean Philanthropists’, they were among the few radicals who were prepared to overturn the government by violence.

Thistlewood and some of his co-conspirators had been involved with insurrection attempts during the winter of 1816-17, when the Spenceans had sought to use the mass meetings held by the orator Henry Hunt at Spa Fields in London to coerce the crowd into pressing the Prince Regent to accept their demands for electoral reform and economic relief. Yet no riots followed: the campaign for political reform and democracy in Britain was deliberately peaceful and legal, to prove the fitness of the working class for suffrage.

The suppression of democratic radicalism at the Peterloo Massacre in August 1819 and the anti-radical Six Acts legislation that followed were the immediate context for the plot. The Spenceans hoped to use Hunt’s return to London in September 1819 as a fresh opportunity to broadcast their agenda to a large crowd. After a series of poorly attended meetings, the ultra radicals lost hope in the potential for mass insurrection.

Violence seemed to be the only way forward. In the event, however, only half of the people expected to turn up at Cato Street did so. Some were attracted by the financial gain offered by informing, but the truth was that the majority of Britons were moderate in their radicalism. Though outraged by Peterloo, they nonetheless sought a legal means of resisting the state.

In his gripping account of the plot, Gatrell examines the lives and circumstances of the individuals involved. This reflects what the late historian of Chartism, Malcolm Chase, identified as the ‘biographical turn’ that dominates current histories of political movements. Gatrell reveals the grim early life of the informant George Edwards, born to a shopkeeper and deserted by his father. It was almost inevitable that in such difficult circumstances Edwards would end up active in London’s underworld, though not that he would also end up playing a defining role in one of the most notorious conspiracies in British history.

Conspiracy on Cato Street: A Tale of Liberty and Revolution in Regency London

Vic Gatrell

Cambridge University Press 474pp £25

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Katrina Navickas is Reader in History at the University of Hertfordshire.