‘Liberty’s Grid’ by Amir Alexander review

Liberty’s Grid: A Founding Father, a Mathematical Dreamland, and the Shaping of America by Amir Alexander explains how the grid system put the United States on the map.

The Great American Grid was not designed to be practical. Instead, the straight lines and right angles were to represent something much more important: freedom. The grid’s instigator was Thomas Jefferson, who regarded the western United States as a tabula rasa for the revolution’s ideas of liberty. He proposed dividing the land into boxes oriented to the points of the compass, to be sold for a standard price. The son of a land surveyor, Jefferson applied to the western territories the ideas of his intellectual hero: Isaac Newton. As a young man, Jefferson had wanted to be a mathematician and he was greatly influenced by Newton’s idea that space exists independently of whether it is occupied by a physical object. Newton held that the area between the vertical and horizontal lines in a grid was empty space, a vacuum of potential. Jefferson believed that this empty space left room for humans to be free.

In Liberty’s Grid Amir Alexander explains how Jefferson used Newton’s ideas to install this now-archetypal feature of the US landscape. However, as the book’s subtitle suggests, Jefferson’s ‘mathematical dreamland’ was always more idealistic than practical. The settlement of the West, and its division into a grid, was predicated on the assumption that the territory was vacant. In fact, much of it was not. Native American ancestral lands west of the Appalachians had been protected by British law, but with the Crown expelled, these rights were annulled. Jefferson brought his proposal before Congress in 1796. Despite opposition from George Washington, who maintained that Jefferson’s lattice design would be impractical, the bill passed. Over the ensuing century and a half, 1.4 billion acres of land were imprinted with the grid.

Several factors made the project intrinsically flawed. Most ironically for Jefferson the mathematician, as well as for Jefferson the philosopher, the equality of the plots was superficial. As Alexander explains: ‘One settler might acquire a plot of rich and level farmland, with a stream flowing near the edge, providing a reliable source of water and a suitable site for a mill. A less-fortunate neighbor might end up in possession of a plot of exactly the same shape and size but made up of bone-dry rocky hills. And all for the same price.’ Furthermore, the plots were set along the lines of the compass. Because of the curvature of the earth, lines of longitude converge as they head north. The further north the plot, the smaller it was.

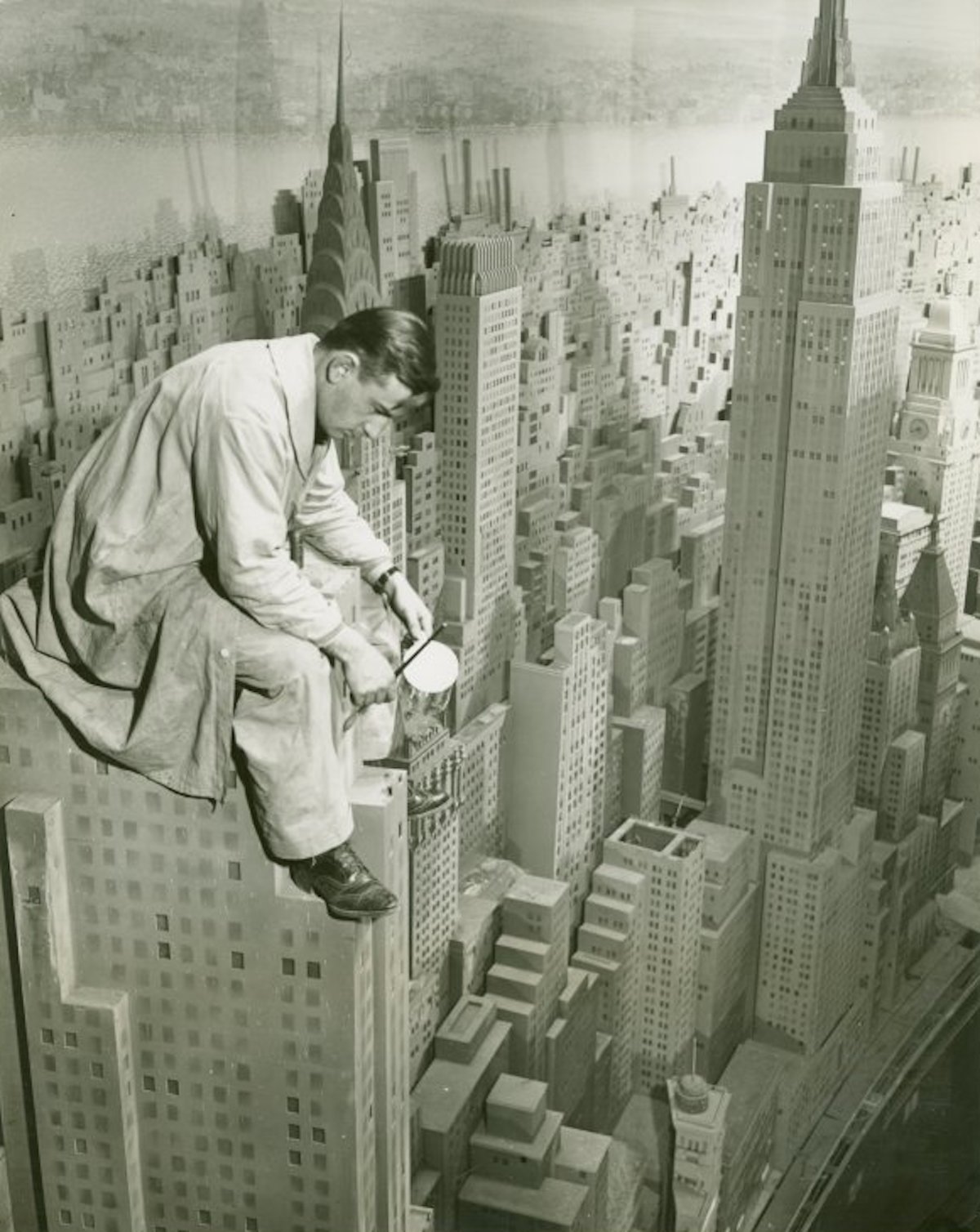

Jefferson’s grid design was also applied to urban areas. Although some colonial cities such as Philadelphia had rectilinear streets, that was not the norm. In 1811 New York initiated a grid in the land north of its historic district, the southern tip of Manhattan. Inspired by Jeffersonian principles, New York created the model for almost every other US city.

Although dominant, the grid was not always trusted. In the mid-19th century, figures such as Henry David Thoreau and the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted regarded Jefferson’s boxes of land not as incubators of freedom, but as restrictive boundaries. Olmsted, who was influenced by London’s Royal Parks and, especially, Birkenhead, fought to establish a refuge from the oppression of New York’s grid. His creation was Central Park.

Despite being a book about straight lines, Liberty’s Grid includes fascinating detours – from Jefferson’s proposals for a metric system, to his suggestions for names of new states: Sylvania, Cherronesus, Assenisipia, Metropotamia. Today, the grid covers two-thirds of the continental US. As Alexander writes: ‘For Jefferson gridded space was empty space, and empty space was where men could be free. It was, in other words, precisely what America was in Jefferson’s mind.’

-

Liberty’s Grid: A Founding Father, a Mathematical Dreamland, and the Shaping of America

Amir Alexander

The University of Chicago Press, 304pp, £24

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Daniel Rey is a writer based in New York.