New Year, Old Books

A new book for the new year is an old British custom, but an old book can be even better.

It is, and of long time hath been, my well-beloved sister, a custom in the beginning of the New Year, for friends to send between presents or gifts, as the witnesses of their love and friendship, and also signifying that they desire each to other that year a good continuance and prosperous end of that lucky beginning.

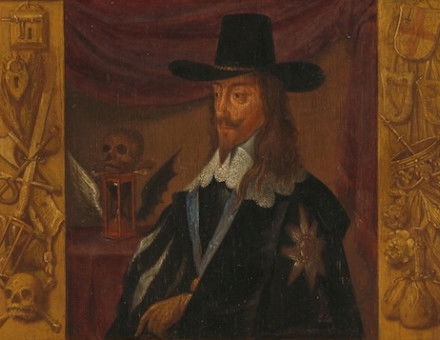

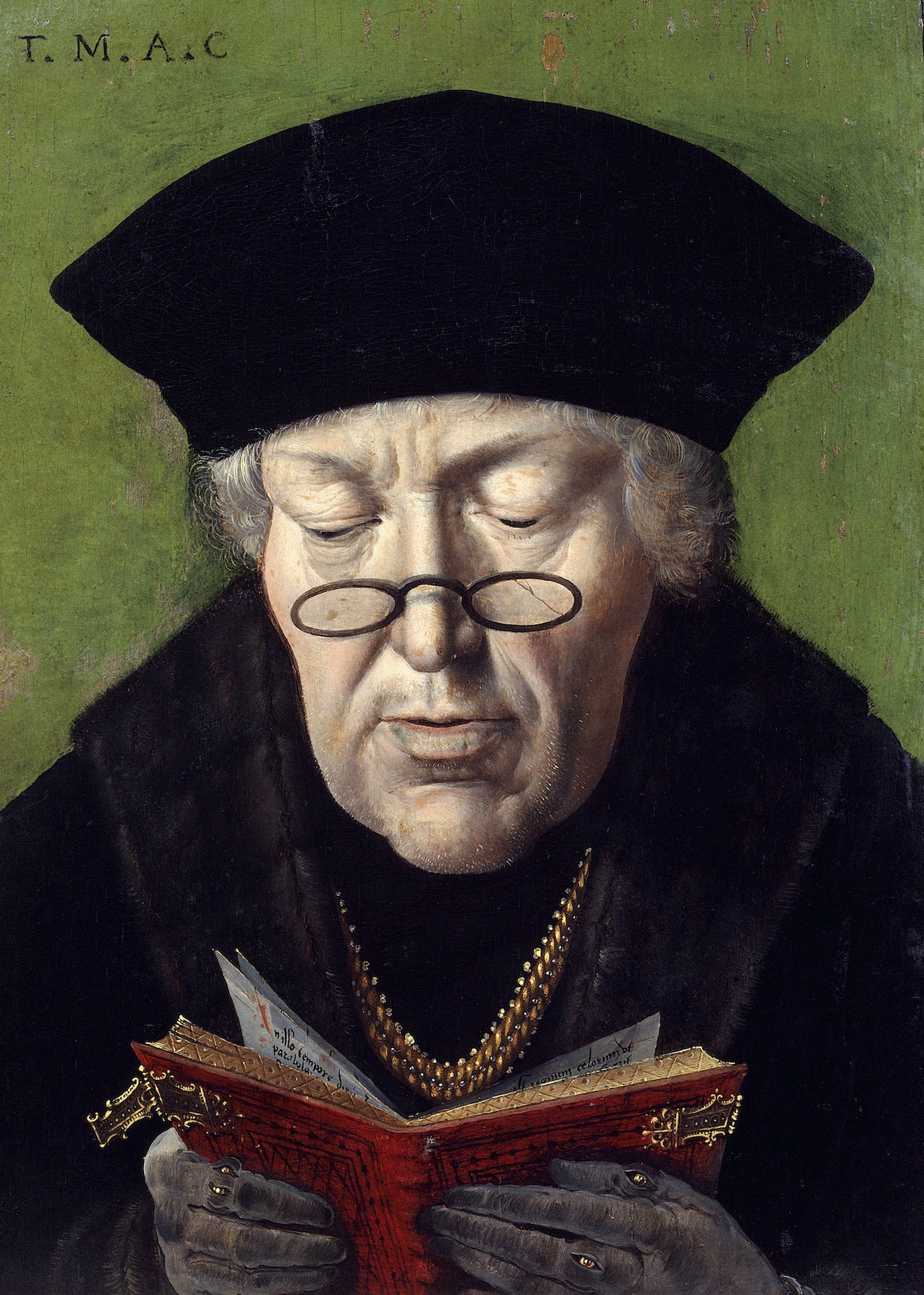

With these words, Thomas More sent a New Year gift in around 1510 to a young woman named Joyeuce Leigh. The tradition he references was a well-established one: before it became customary in Britain to exchange presents at Christmas, New Year was the usual time for giving gifts, with the intention that they would be a token of luck for the year ahead. As More goes on to say, people often gave food or clothes, ‘such things as pertain only unto the body, either to be fed or to be clad or some other wise delighted’.