The Allure of Medieval Churches

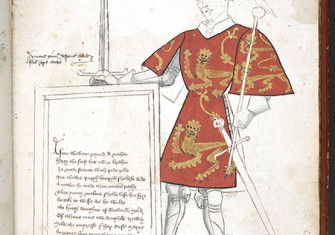

The ancient stones of churches are portals to the past. Each new generation becomes a custodian.

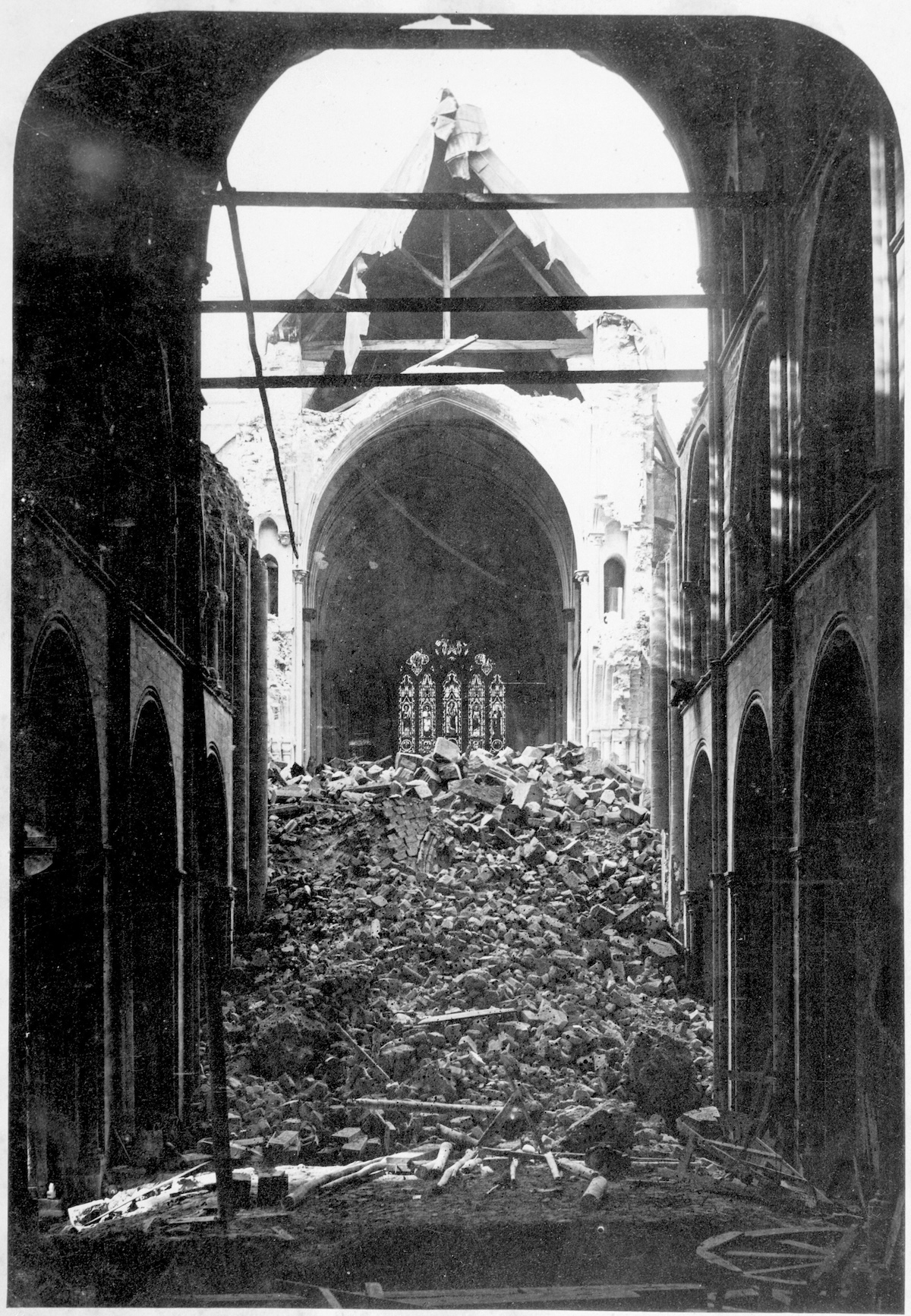

In the 1860s a young architect arrives in a small town in southern England. He has been sent to renovate the town’s great church, a splendid medieval building which has fallen into disrepair. The roof is leaking, the fabric is mouldering and as the floor decays the local doctor worries infection will spread from the graves beneath the church; the dead, he fears, will begin to poison the living.

But the architect realises at once that the church’s problems run deeper than this. Its massive tower is too heavy for the building. It has been slowly shifting for centuries and he seems to hear the voices of its arches crying out: ‘They have bound on us a burden too heavy to be borne. We are shifting it. The arch never sleeps.’ No one heeds his warnings; collapse is only a matter of time.