Make Believe

Historians are tethered to the archive, but sometimes fixing the gaps requires the techniques of a novelist.

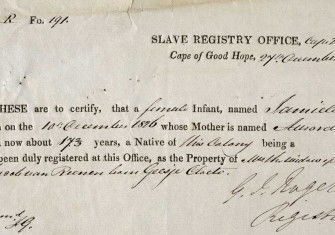

In 1987 one of my great historical heroes, Natalie Zemon Davis, published Fiction in the Archives. It focuses on the ‘fictional’ elements of royal letters of pardon and remission in 16th-century France, by which Davis meant how the tales in such letters were crafted into narratives, acts of literary creation, even as they told the teller’s truth about their life and the crimes for which they sought pardon. In an earlier work, The Return of Martin Guerre (1983), after introducing the extensive documents she had consulted, Davis stated that when she could not find her individual man or woman, she had relied on other contemporary sources to get a sense of what they might have seen or felt: ‘What I offer you here is in part my invention, but held tightly in check by the voices of the past.’ Prompted by Davis and the work of another pioneering scholar, Saidiya Hartman, I want to consider fictions in the archives and the history books.