Shaken and Stirred: A History of James Bond

For over half a century, James Bond’s mix of ‘sex, snobbery and sadism’ has proved enduringly popular, outlasting the Cold War that birthed him. Why?

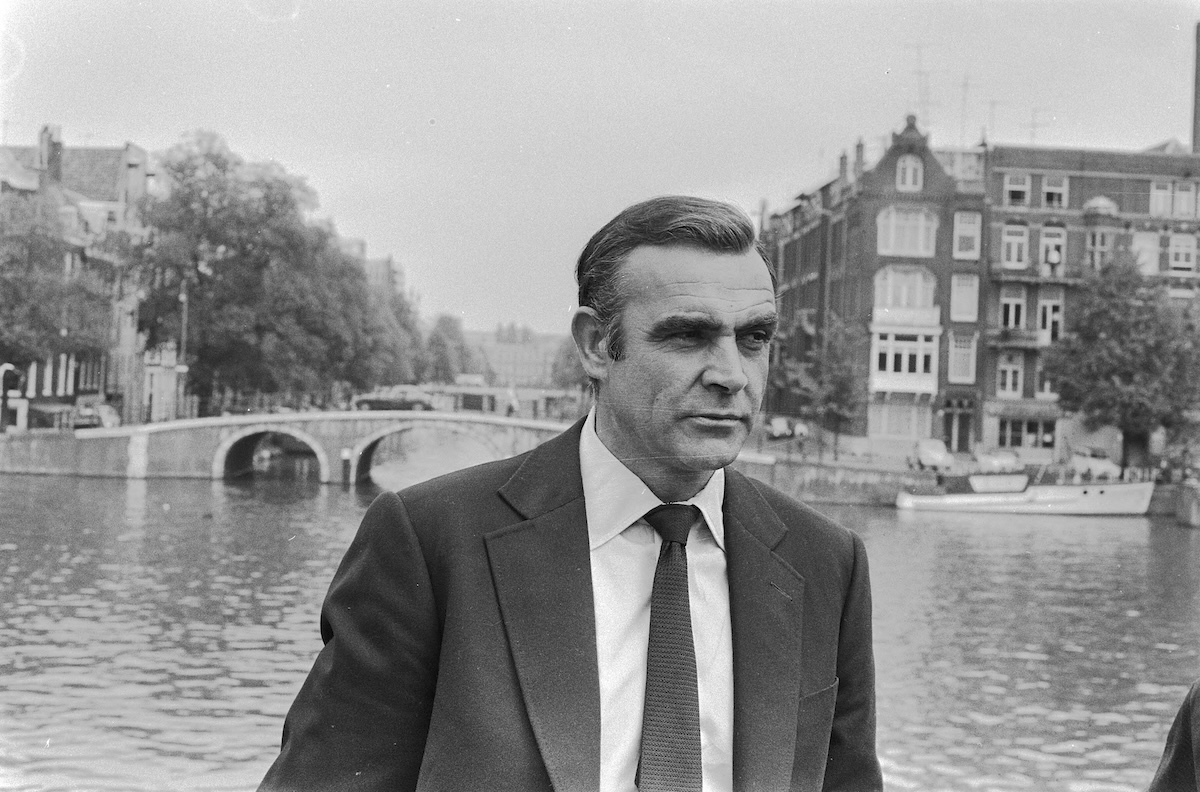

On October 5th, 1962 Dr No premiered at the London Pavilion and made a relatively unknown Scottish actor, Sean Connery, a star. Sent to Jamaica to investigate a suspicious disappearance, the British spy James Bond (007) eventually tracks the killer and a previously unknown secret organisation to Crab Key. With the help of an innocent girl called Honey Ryder, famously dressed in a white bikini, Bond confronts the first of many evil geniuses intent on implementing plans for global domination. Dr No, a disfigured but gifted scientist, reveals that he works for SPECTRE (Special Executive for Counter-Intelligence, Terrorism and Revenge and Extortion). The organisation is planning to sabotage the US space programme in nearby Florida in order to wreak havoc and trigger a conflict between East and West. SPECTRE hopes the United States will attack the Soviet Union in retaliation. Bond, after evading capture and assassination, kills Dr No and scuppers the plot.