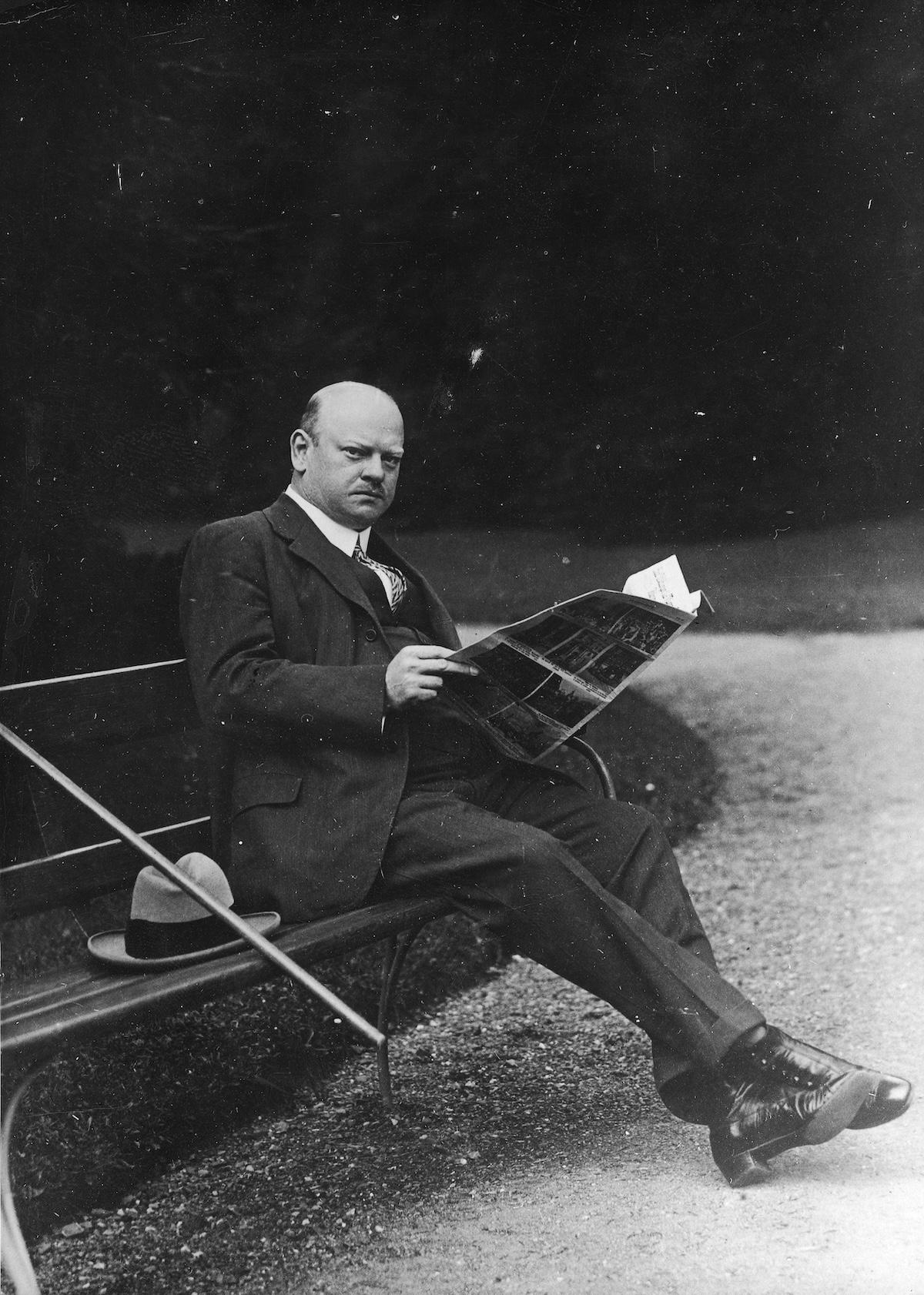

Gustav Stresemann: Weimar’s Greatest Statesman?

Gustav Stresemann was at the heart of government until he died in 1929. Had he lived, could he have steered Germany safely through the Weimar era?

Gustav Stresemann became Chancellor of Germany in August 1923 at a time when it seemed as though the state was about to break up in chaos. With the French occupying the Ruhr coalfield, the mark suffering hyper-inflation to the point where it ceased to be a viable currency, separatists active in the Rhineland, Hitler in Bavaria and Communists in Saxony plotting different versions of revolution, the army wavering in its loyalty and Stresemann’s own party far from united behind him, it was a desperate time. He wrote to his wife Käte that to become Chancellor in such circumstances would be ‘all but political suicide’.