Aliens and the Enlightenment

In the 18th century the existence of extraterrestrial life went from debatable hypothesis to fundamental tenet of Enlightenment thought.

For millennia everybody knew that human beings enjoy a privileged, unique position at the centre of the universe. That self-confidence began to crack after Nicolaus Copernicus suggested that the Earth goes round the Sun and an exciting but frightening possibility emerged: could life exist on other planets?

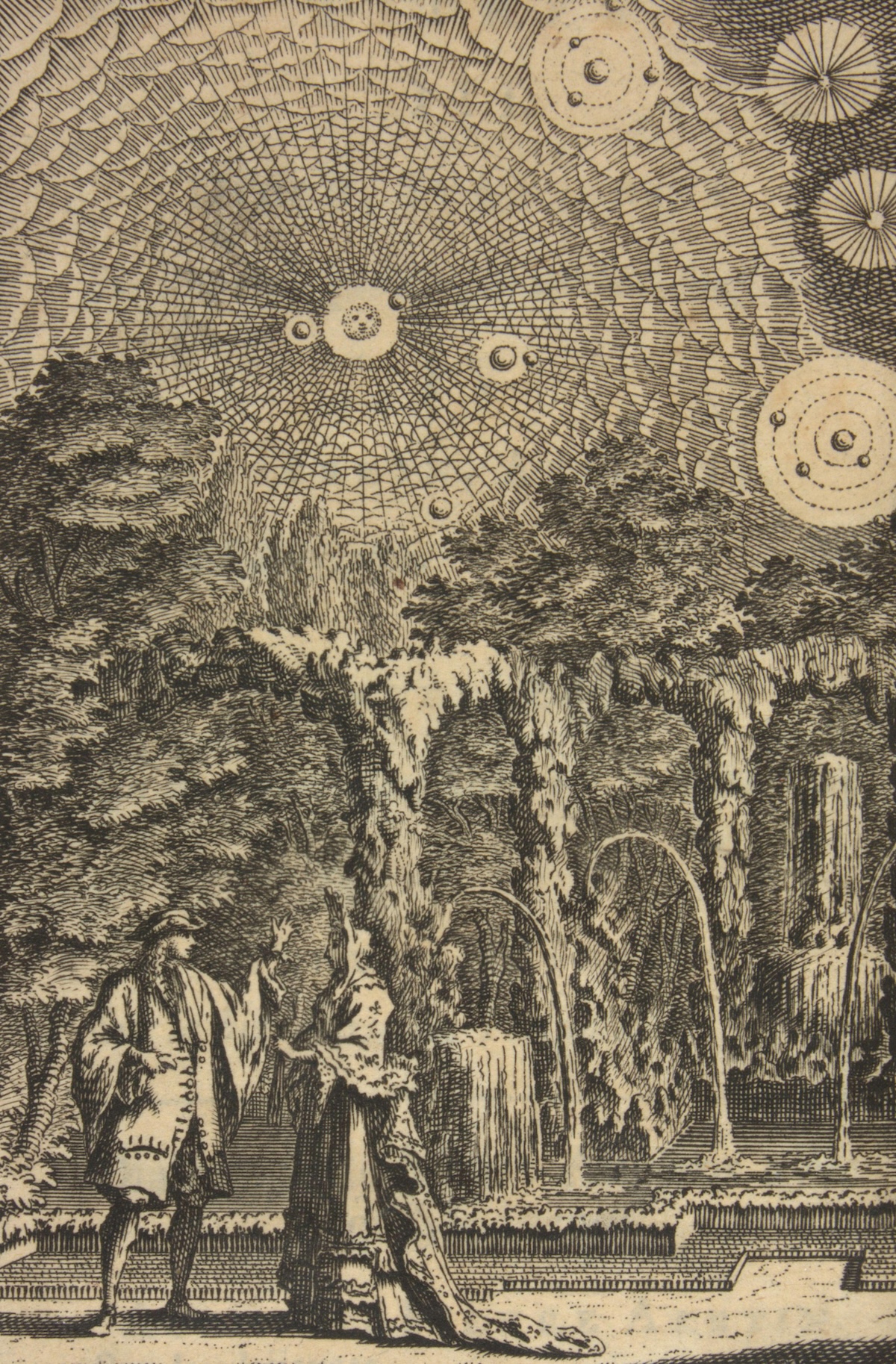

For the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande it was a no-brainer. After all, he explained, if you saw a flock of sheep in the distance you would never infer that some of them had stones inside their bodies instead of entrails as humans do. Similarly, since the planets resemble the Earth, they must be inhabited. But even for those who accepted that logical leap, uncertainties were multiplying as increasingly high-powered telescopes revealed more and more stars. Might other planetary systems exist? Could they also support life?

Like Lalande, many writers argued by analogy, a rhetorical technique that then punched considerable weight. Fuelled by scientific, religious and philosophical beliefs, discussions about the plurality of worlds – the expression used at the time – flourished throughout the 18th century.