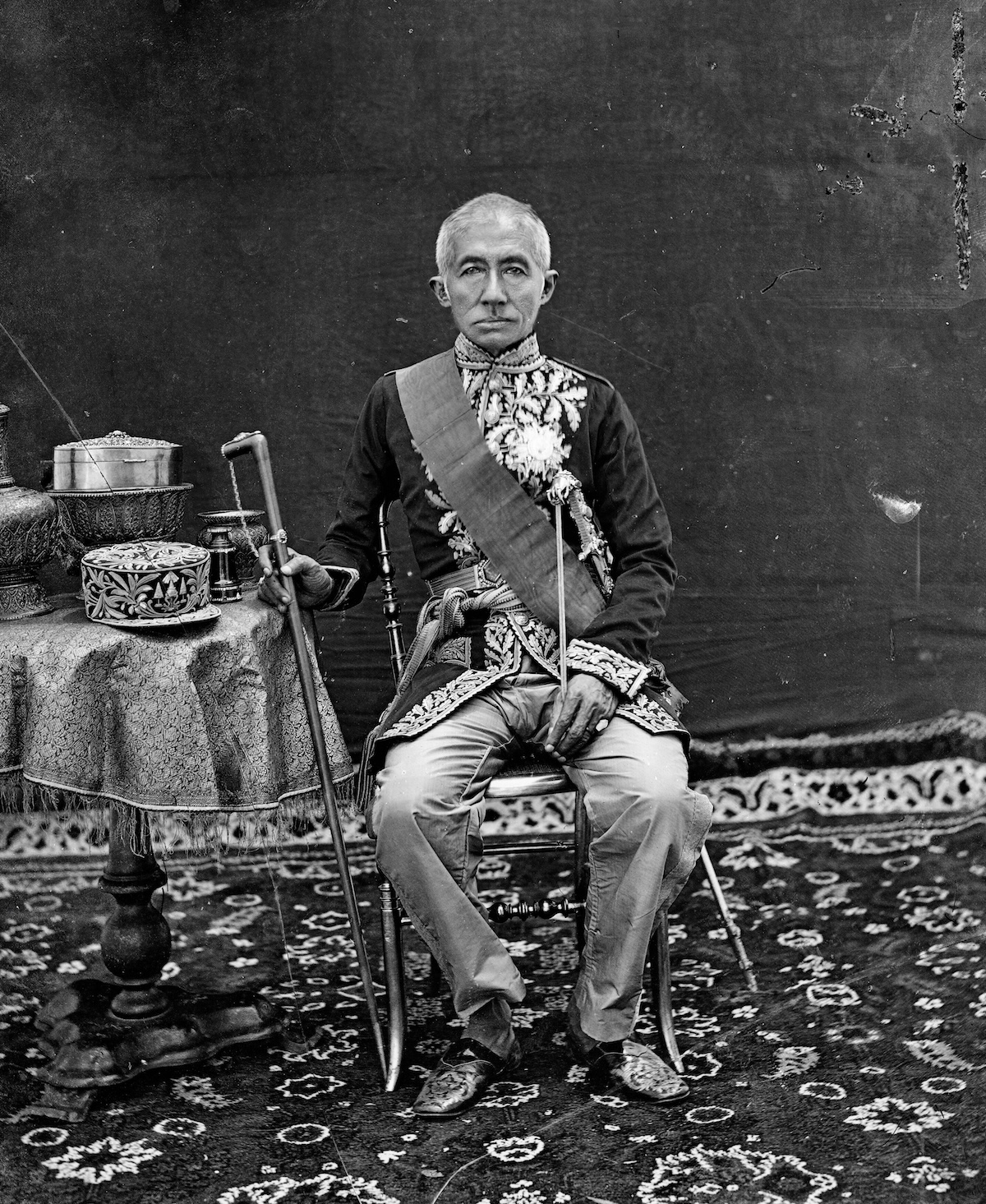

Death of the King of Siam

On 1 October 1868 King Mongkut – who reigned as Rama IV – passed away having trod a delicate course to keep Thailand free of European empires.

When his father, Rama II, died in 1824 the Siamese throne went to Mongkut’s older half-brother, who ruled as Rama III. Mongkut, aged 19, joined a monastery. Three months was customary. Mongkut stayed for 27 years.

While in orders Mongkut led a new, reformist religious movement which aimed to strip away later accretions to the Buddha’s teachings; he mocked the dominant older order, the Mahanikai, as the Order of Long-Standing Habit. In 1833 he discovered a late-13th-century stele which described the simpler judicial and religious customs of an early Thai king, Ram Khamhaeng. It seemed so apt some doubted its authenticity.

But when Mongkut became king himself in 1851, ruling as Rama IV, the clarity of historic virtues couldn’t solve every problem. China had recently been humbled by the British in the Second Opium War. ‘There will be no more wars with Vietnam and Burma’, Rama III had said. ‘We will have them only with the West.’

Mongkut was fascinated by Western materialism, but disdainful of its missionary pieties. He offered modernity a cautious approval; but edicts were still issued ‘by royal command reverberating like the roar of a lion’. He had reason for caution. Britain’s John Bowring arrived in 1855, all etiquette and belligerence. He had a ‘large fleet at [his] disposal’, he told Mongkut, but he had no desire to be ‘the bearer of a menacing message’. Mongkut signed the offered treaty: it wasn’t so much gunboat diplomacy as gunboat globalisation.

Almost identical agreements were quickly signed with the United States, France, Denmark, Portugal and many others. Mongkut played them all against one another; Siam alone remained free of imperial dominion in the region.

Mongkut knew Latin and spoke English fluently, if ‘with a literary tinge’, one of his teachers said. He studied science and maths, but astronomy was his passion. In August 1868 he led an expedition to view an eclipse, the arrival of which he had predicted himself. It arrived, but he caught malaria. On 1 October 1868, observing that he was dying, Mongkut asked to be turned on to his right side, as the Buddha had been on his death bed. ‘This is the correct way to die’, he said, precise to the end.