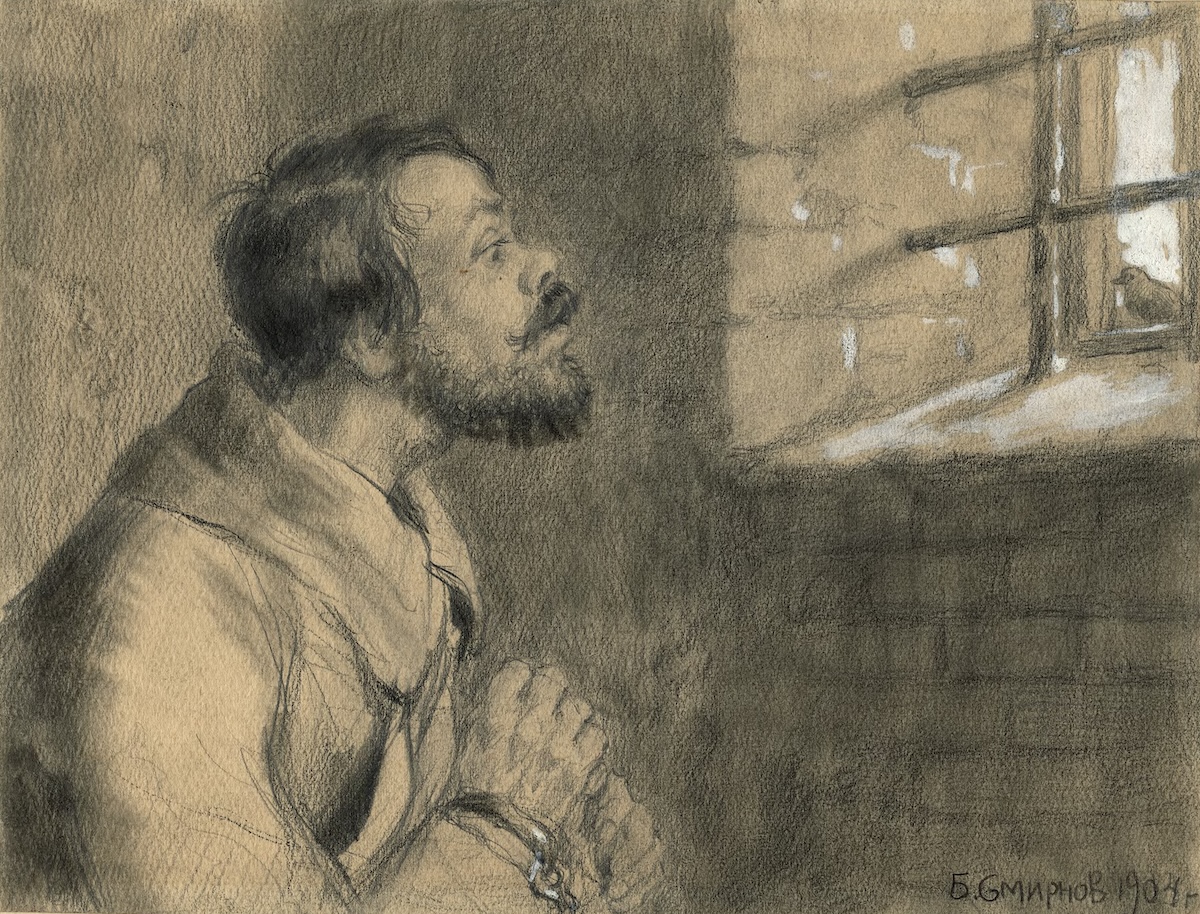

Siberian Exile in Tsarist Russia

The wastelands of Siberia provided Tsarist Russia with ‘a vast roofless prison’ for criminals and political prisoners banished into exile.

Russia’s huge Asiatic hinterland of Siberia has always figured in the Western popular imagination as a limitless frozen wilderness, a place of punishment and exile for the unfortunate victims of Tsarist and Soviet authorities. Dostoevsky languished there for several years and afterwards described it as The House of the Dead , while an official government report of 1900 referred to, but dismissed, the concept of Siberia as ‘a vast roofless prison’. More recently Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago has reinforced this sombre and inhospitable image, which, while being an essential, though sinister, aspect of Siberia’s history, is by no means the whole story.