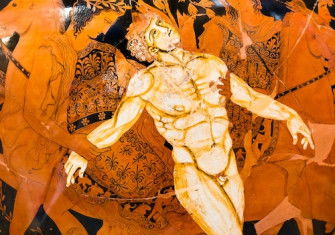

Restoring Faith: Crete’s Ancient Minoan Civilisation

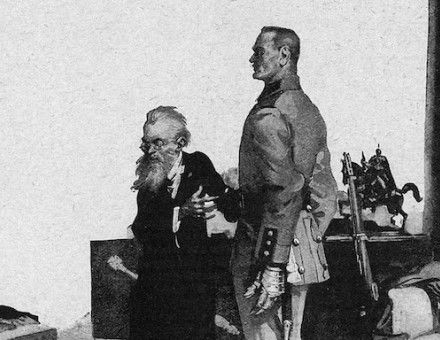

At the end of the 19th century, British antiquarian Arthur Evans sought to ‘re-enchant’ the world with his utopian interpretation of Crete’s ancient Minoan civilisation.

In 1830 Auguste Comte laid out his scheme of the three phases of human development, culminating in the 'positive' stage in which belief in demons and gods would be supplanted by an understanding of natural laws. Just eight years later, Charles Darwin began his descent from a robust young man to a neurotic invalid as he wrestled with the atheistic implications of his theory of natural selection. Friedrich Nietzsche announced the death of God in 1882. In 1919, Max Weber unveiled his argument about the progressive 'disenchantment' of the world caused by the decline of religious belief.