Panipat: The Mughals Strike Twice

The two 16th-century battles of Panipat are little known in the West. But they were pivotal in establishing the Mughal Empire as the dominant power of northern India.

The creation of the Mughal Empire was arguably the crucial event of the early 16th century. The Spanish overthrow of the Aztec and Inca empires in Mexico and Peru, respectively, was of enormous importance, but the percentage of the world’s population in the New World was small, while more than half of it lived in East and South Asia. The Mughal Empire was a major force from its creation until the start of the 18th century and was still something of its former glory into the 1850s.

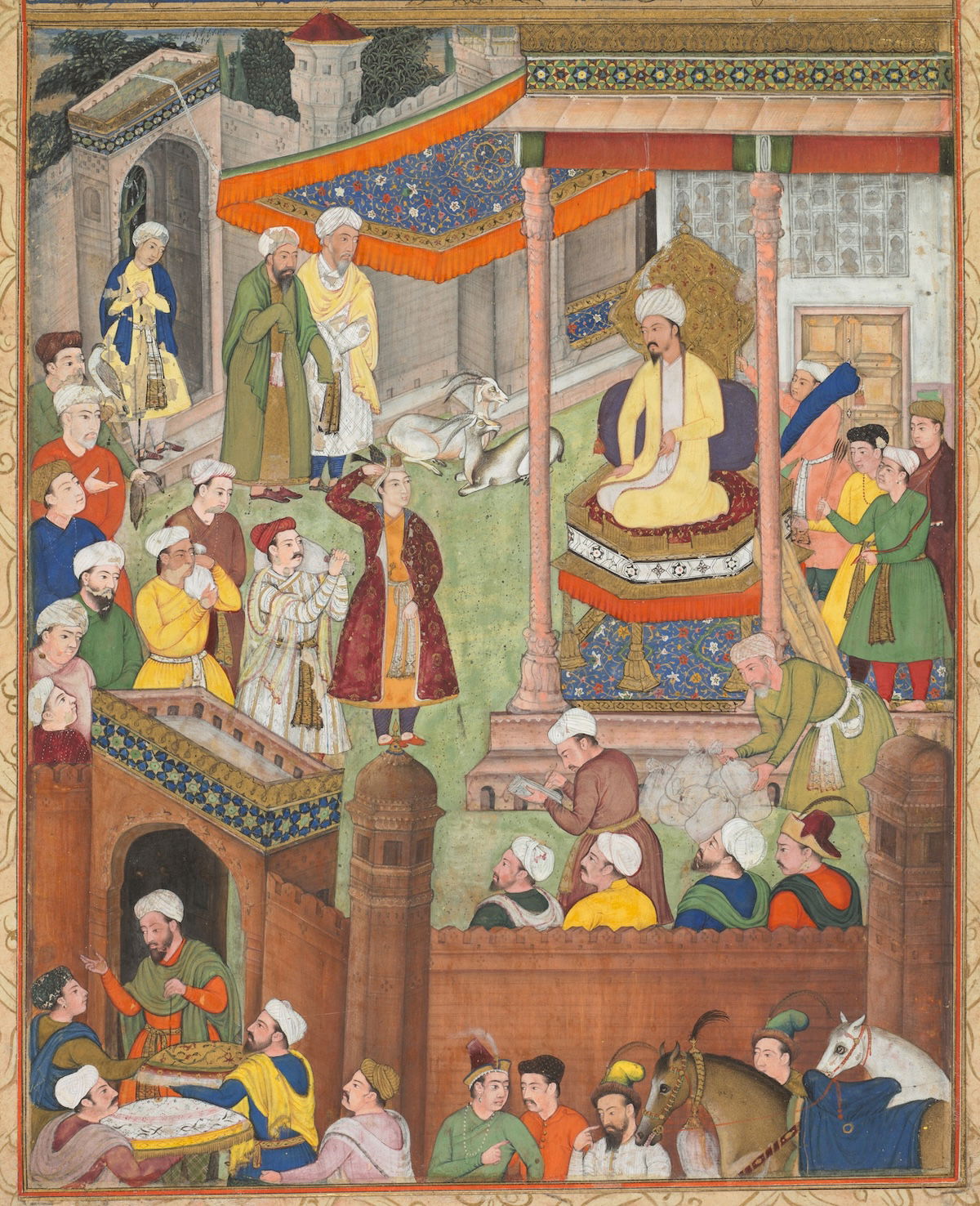

The Mughal Empire was created by Zahir-ud-din Muhammad Babur (1483-1530), a general and ruler of determination, bravery and skill. He emerged from the confused politics of Central Asia, one more example of a ruler from the steppe able to overthrow more traditional, settled states. The two great empires of Genghis Khan (c. 1162-1227) and Tamerlane (1336-1405) had been exceptionally successful in extending their sway, as their opponents had no answer to the military tactics they deployed, especially their light cavalry armed with powerful bows. Babur strove to repeat their success.

Yet from the perspective of his time the achievements of Babur and his successors were hard won. The Lodi sultanate of Delhi, which Babur was to overthrow in 1526, was then still an expanding power in northern India; while the major force in Central Asia was the Uzbeks, whose dynasty was descended from Ghengis Khan’s son, Jochi (c. 1181-1227).

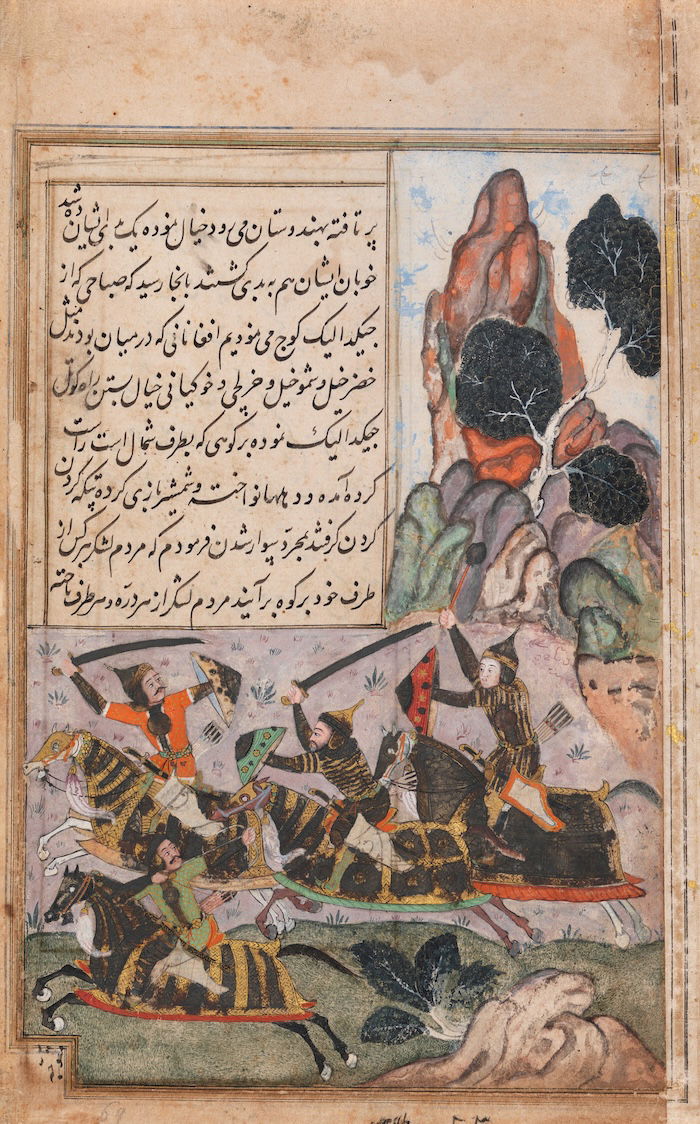

Babur had succeeded his father, Umar Sheykh Mirza (1456-94), as ruler of the principality of Fergana, Babur’s birthplace (now in Uzbekistan). In 1497 Babur’s forces also occupied the city of Samarkand, but were driven from both by the Uzbeks, who defeated the Mughals at Sar-e-pul in northern Afghanistan in 1501, one of many cavalry battles that were so important to the fate of states in Eurasia.

Having lost Fergana and Samarkand to the Uzbeks, in 1504 Babur captured the cities and regions of Kabul and Ghazni in modern Afghanistan. His control of them became the basis of his subsequent interventions in the Punjab and northern India. For the moment, however, Babur sought to recover his earlier territories and his struggle with the Uzbeks ended in defeat, when they routed his Safavid allies at Ghajdewan near Bukhara in 1514. Babur was able to shift his attention to the wealthy agricultural zone of the Punjab in north-west India. He saw the region as his rightful heritage as a descendant of Tamerlane, who had conquered the Punjab prior to capturing Delhi in 1398. Babur’s conquest of this prestigious and bountiful region helped compensate psychologically for the loss of his homeland.

He benefited, too, from the growing weakness of the Lodis, who were riven by internal strife. In addition they had to deal with rebellious Afghan emirs and a revolt in east Punjab, led by Ala al-Din ’Alam Khan Lodi against his nephew, Ibrahim (r. 1517-26), the Lodi Sultan of Delhi. Babur intervened, annexed Lahore and the entire Punjab in early 1526 and then proceeded to attack Ibrahim in Delhi. Babur’s invasion was encouraged by opponents of the sultan, who provided him with important manpower, although the promised supporting attack by Rana Sanga (1484-1527), head of the Rajput state of Mewar, failed to materialise.

At the first Battle of Panipat, north of Delhi, on April 21st, 1526 (there were to be further battles there in 1556 and 1761) Babur successfully employed both matchlockmen and field artillery against the Lodi cavalry, whose far larger army lacked firearms. Babur had been impressed by the role played by firearms in the Ottoman victory over the Safavids, who also lacked them, at Chaldiran (now in north-west Iran) in 1514. Nevertheless, the challenge posed by the approximately 100,000-strong Lodi army was magnified by the mobility and speed of its cavalry and by the slow rate of fire of the Mughal firearms. As a result, Babur chose a battlefield that would limit the mobility of the enemy cavalry and delay its advance, as well as countering both his opponent’s weight of numbers and war elephants. Like the English at the Battle of Crécy in 1346, Babur selected a position for his 12,000 troops between two blocks of forest, which channelled the Lodi advance and, to delay it, deployed a line of wagons linked by ropes of hide, a strategy known as tabur cengi (camp battle). Digging a ditch strengthened the forest cover for his flanks.

The Lodis did not attack initially, but the great size of their army posed a logistical challenge that finally forced them to advance; tactics are always dependent upon logistics, a fact that tends to be underplayed because of our limited knowledge of such details in this period. Frightened by Babur’s cannon, the 100 or so elephants in the van stampeded back through the Lodi army, whose subsequent cavalry attack failed to pass the wagons and was cut down by Mughal fire at close quarters. With the Lodis hit hard, Babur made gaps in his wagon line, while his cavalry, held in reserve, attacked through them, wreaking havoc. The precise course of events is difficult to establish and it is unclear whether divisions in the Lodi regime helped account for battlefield deficiencies. Babur’s own version acknowledged the role of his cannon, but also put much emphasis on his mounted archers, who succeeded in passing the Lodi flanks and attacked the army in the rear:

Ustad Ali Kuli discharged his guns many times in front of the line to good purpose. Mustafa, the cannoneer on the left of the centre, managed his artillery with great effect. The right and left divisions, the centre and flankers having surrounded the enemy and taken them in the rear, were now engaged in hot conflict, and busy pouring in discharges of arrows on them. They made one or two very poor charges on our right and left divisions. My troops making use of their bows, plied them with arrows, and drove them in upon their centre.

Contracting under the hail of arrows, the vulnerable Lodi army was in a similar position to the Romans under Carthaginian attack at Cannae in 216 bc, during the Second Punic War. The successful combination of infantry in defence and mounted archers in attack indicates the importance of combined arms tactics, a point true of many famous victories.

A pursuit of the vanquished army was necessary in order to gain full advantage from the victory, but the death of Ibrahim and most of the rest of the Lodi elite at Panipat removed any remaining barrier to the establishment of Mughal power. Agra, Delhi and much of the sultanate fell rapidly after the battle.

In 1527 Babur pressed on to defeat Rana Sanga and his Rajput Confederacy at Kanua, south-west of Delhi, on March 16th. Mughal firepower again played a role in this defeat of the frontal attack by Rajput cavalry and elephants. The flexible enveloping tactics used by Babur’s cavalry proved highly effective and mounted archers were probably at least as important as the infantry matchlockmen in the course of the battle. Firearms, especially combined with skilful leadership, proved significant in the early stages. The Mughal position was again fortified with a ditch and wagons linked by chains and the matchlockmen, placed in the front of the force, ‘broke the ranks of the pagan army with matchlocks and guns like their hearts’; they were black and covered with smoke. The Mughals had only about 12,000 troops at Kanua, whereas the Rajputs, allegedly, had 80,000 cavalry and 500 elephants. After his victory, Babur, in the fashion of Tamerlane, built a tower of the skulls of the dead ‘infidels’: the Rajputs were Hindus.

The Afghans, the foundation of Lodi military power, continued to resist the Mughals in northern India, but Babur brought an end to Afghan resistance in the region of Bihar, in eastern India, where Ibrahim’s brother, Mahmud, was established as an independent king, defeating his forces at Dadra, near Lucknow, in 1531.

Mughal power weakened under Babur’s opium-addicted successor, his son Humayun (r. 1530-56), who was challenged by Sher Khan Sur (1486-1545), an able Afghan who had served first Ibrahim Lodi and then Babur, only to leave the service of the latter in 1529 because he saw few hopes of advancement. Based in Bihar, he instilled discipline by paying his Afghan troops well. Sher Khan conquered most of Bengal between 1534 and 1538, bringing to an end the independent state ruled by the Husain Shahi dynasty. Their capital, Gaur, in west Bengal, fell in 1538 and this challenge led Humayun to march east, only for Sher Khan to cut off his line of retreat. Outmanoeuvred, Humayun was defeated at Chausa, in Bihar, in a surprise attack in June 1539 and Sher Khan declared himself an independent king, Sher Shar.

In May 1540, a decisive victory over a demoralised Mughal army at Kanauj, now in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, led to a transformation of the situation in north India, one that tends to be ignored in works on global military history, which suggest a smooth pattern of Mughal advance, not least for western audiences. The defeated Humayun fled India and Sher Shar captured the Mughal centres of power, Delhi and Agra, as well as the Punjab. He revived the Delhi sultanate and founded the Sur dynasty. Before a fatal explosion during the siege of Kalinjar ended his life in 1545, Sher Shar had taken possession of much of northern India, conquering more than either the Lodis or, at that stage, the Mughals. Malwa was conquered in 1542-43, while Mewar submitted in 1544. Moreover, Sher Shar revitalised the government by asserting central control, reviving earlier administrative practices and adding the vital ingredient of personal commitment. He also used Ottoman artillery specialists to help manufacture a large number of cannon and he commanded a substantial force of gunners.

Humayun continued to challenge Sher Shar, a reminder of the extent to which decisive victory in battle depended on the killing of opposing leaders. He failed, however, to establish himself in the region of Sind, beyond Sher Shar’s dominions, and subsequently to win the support of the Rajputs, still a major force in northern India. As a result Humayun left India for good in 1543 seeking exile in the Safavid Empire. Good past relations between Babur and the Safavid rulers led to a friendly reception for Humayun. However this entailed him becoming in effect a client, converting to Shi’ism. He was given an army of 12,000 men, with which he conquered Kandahar in southern Afghanistan from his brother Kamran in 1545. The Safavid Shah of Persia, Tahmasp (r. 1525-76), had insisted that Kandahar be handed over to him, but when most of the Safavid troops returned home Humayun took control, pressing on with repeated campaigns until 1550, when he recaptured Ghazi and Kabul from Kamran, who, once defeated, was blinded so that he could not lead fresh rebellions. Humayun’s conquests in northern Afghanistan, where in 1546 he took over Balakhshan and in 1549 attacked Balkh, showed that the mountains of central Afghanistan were no bar to military campaigning.

The Sur sultanate declined under Sher Shar’s successors. His son, Islam Shar (r. 1545-52), resisted a number of revolts, but his death was followed by the break-up of the empire between relatives in 1553, followed by a combination of civil war and revolts. Humayun grasped his opportunity in 1555, advancing from Afghanistan into the Punjab, as his father had done in 1526, where he won battles at Dipalpur and Machhiwara and recaptured Delhi and Agra.

Humayun died in an accident in Delhi on January 27th, 1556 and was succeeded by his son, Akbar (r. 1556-1605), who was just 14. Akbar’s Iranian-born regent, Bairam Khan (d. 1561), proved effective, decisively defeating the Sur governor of Delhi and would-be ruler Himu (1501-56) at the second Battle of Panipat on November 5th, 1556, following Himu’s capture of Delhi and Agra the previous month. Victory in the battle again brought the Mughals control of Delhi and Agra, a further example of the extent to which defeat was usually followed by the fall of cities, because they were vulnerable militarily to whoever controlled the surrounding countryside and because there was little political logic to supporting a defeated ruler.

At the second Battle of Panipat the Mughal army defeated its much larger foe without the use of tabur cengi tactics or, apparently, artillery. Himu relied on an elephant charge, but the Mughal centre redeployed behind a ravine and eventually prevailed, thanks to its mounted archers. Himu was wounded by an arrow. The fate of commanders was important to the course of battles: they chose the terrain on which to fight and decided when to launch attacks and deploy reserves; they also led attacks and their presence could consolidate defence. These factors were not ones that could readily be dispensed with, but they also exposed commanders to the risk of death, capture or injury, with the consequent loss of morale for their men. In the aftermath of the second Battle of Panipat, the captured Himu was executed under the orders of Bairam Khan.

The second Battle of Panipat witnessed the contest of Indian and Central Asian styles of warfare. Drawing on their roots in Central Asia, the Mughal ability to control the supply of war horses in India ensured that they dominated mounted archery in the subcontinent. Archery played a major role in the decline in the importance of elephants, hitherto significant in north India. By contrast, in Kerala, in southern India, a forested region that was unsuitable for mounted archers, elephants continued to play a role, as they also did in the similar environment of South-east Asia. Elephants never played a comparable role in Africa, primarily because African elephants are more difficult to train.

During his four-year regency, Bairam Khan had pressed on to defeat the Sur princes, helping to restore Mughal control over much of northern India, encompassing the territories of Oudh, Gwalior, Ajmer and Mewar. Sikandar Sur, who had ruled Punjab from 1553, capitulated to the now mature Akbar at Mankot in 1557, bringing the Sur dynasty to an end. Having won control from Bairam Khan in 1560-61, in part due to Sunni objections to Bairam as a Shi’ite, Akbar also had to displace hostile relatives, notably his foster brother Adham Khan, whom he threw to his death from a harem balcony.

Once in full control, Akbar expanded the Mughal Empire, although the divisive nature of his family ensured that, in 1566, he had to repel an attack by his half-brother, Muhammad Hakim, the ruler of Kabul, who had allied with the Uzbeks, the Mughal’s traditional enemies. As with other dynasties, such as the Ottomans, disputes within the ruling house were closely linked to international rivalries. Swift moves were crucial to Akbar’s success, in gaining the initiative, in overcoming distances and in asserting his interests and will in a complex political environment. The basis of imperial power was now firmly established and by the time of his death in 1605 Akbar had fully established the Mughal Empire in northern India.