Aurangzeb versus the East India Company

‘Trade follows the flag’ is a truism of imperial expansion but in the 1680s it was the other way round, as the East India Company attempted to challenge the might of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.

The English East India Company was chartered by Elizabeth I on the last day of 1600. With the benefit of hindsight we know that it was destined to win for itself a spectacular territorial empire in India, and that the decisive step towards that empire was the seizure of power in the two great provinces of Bengal and Bihar by one of the Company's military servants, Robert Clive, in 1757. By his victory in a battle at Plassey which cost less than twenty English lives, Clive laid the foundations of a British Raj in India which lasted until 1947. It is a platitude amongst historians of the expansion of Europe that, compared with their achievements in the Americas, Europeans built their territorial empires in Asia belatedly. If all Europeans had been expelled from the Orient as late as 1750, they would have left precious little trace behind them, except in the Philippines, where, alone, the Spaniards had managed to rerun something like their dramatic conquests of non-European peoples in Mexico and Peru. The British are generally thought not even to have considered the forcible acquisition of a territorial base in India until the unexpected success of French attacks on their position in south India in the 1740s and 1750s compelled them to create the military machine in India which Clive then turned against Bengal.

Read our India Special on the History Today app. Download it now for Apple or Android.

This is, however, not so. Clive was the second Englishman to lead a powerful force or troops and ships to Bengal. In the late 1680s, the English East India Company, under the leadership of a formidable City financier, Sir Josiah Child, embarked on a deliberate policy of using armed force to achieve its objectives in India. This extraordinary episode deserves more attention than It has hitherto been given, for two main reasons. One is the inherent difficulty of explaining why an East India Company founded by cautious merchants determined to stick to business and spurn conquest, ended up declaring war on the vast Moghul Empire which, under its last great sovereign, the Emperor Aurangzeb, had, by 1700, extended its formal boundaries over virtually the whole sub-continent. By implication we might hope in the course of probing this question to gain an insight into the aggressive and authoritarian spirit of late Stuart England, for the underlying thrust of a regime is often more apparent at the periphery of its power than at its centre. The second reason for studying this episode is the comparative material it provides for analysing the eventual transition to British supremacy in Bengal. The explanation of Child's failure must throw into high relief some of the reasons for dive's success.

The early history of the East India Company certainly showed no hint of its future territorial greatness in India. It was founded as a strictly business enterprise to gain access to the lucrative oceanic commerce in spices from the Moluccas and other islands in what is now Indonesia. Queen Elizabeth, who chartered it, left not an inch of new colony to her sucessor James VI and I. It is true that under James an infant British overseas empire was born, but it was a sickly child struggling for survival in the 1620s when Spaniards ravaged its Caribbean toeholds, American Indians mauled Virginia, and the English colony in Newfoundland entered on a terminal decline. When William Alexander, Earl of Stirling, tried to create a North American colony for Scotland in Nova Scotia, it proved impossible, economically and politically, to maintain a settlement in such bleak northern latitudes, and in 1632 Charles I surrendered what there was of Nova Scotia as part of a peace settlement with France.

The East India Company made a profitable enough start in a series of voyages aimed primarily at the Spice Islands rather than India. Indeed, it was not until 1608 that one of its ships, on the third organised voyage, touched at the Indian port of Surat in Gujerat on the western or Malabar coast. The Company went through what has been called a 'hard infancy': the Dutch pursued a vendetta against their English rivals in the Spice Islands, culminating in the 1623 Massacre of Amboyna in which they executed several English merchants on trumped-up charges and, in the words of Henry Robinson (writing in 1649), 'by which straregem of theirs they have almost worried us out of the East India trade'. That was an exaggeration, but the East India Company turned increasingly to India, and tried to tailor its coat according to its shrinking cloth. Between 1610 arid 1619 the Company built and used large vessels like the Trades Increase and the Great James of around a thousand tons burthen. Since its exports were mainly bullion and its imports,although high in value, were modest in bulk, it did not need such ships. (In a year the Company brought home perhaps one or two thousand tons of pepper, about the same of salt, and a few hundred tons of silks, cottons, and dvestuffs.) The 1620s saw a sensible halving of the tonnage of the average Company ship.

The Company was always deeply averse to becoming involved in local politics and wars; even a policy of seizing and fortifying bases was financially impractical. It had to be prepared to fight at sea, as its ships did in 1612 and 1615 to crack the Portuguese protection racket on the Malabar coast, but it knew that war ate up profit. Between 1615 and 1618 the East India Company financed the embassy of Sir Thomas Roe from James VI and I to the court of the Emperor Jahangir. Roe achieved little, but he summed up received wisdom when he wrote:

It is the beggering of the Portugall... that he keepes souldiers that spendes it; yet his garisons are meane. He never Profited by the Indyes, since he defended them. Observe this well. It hath beene also the error of the Dutch, who seek Plantation heere by the swoord.

The establishment of Fort St George (the embryonic future city of Madras) on the eastern or Coromandel coast of India in the 1640s was not proof that the Company had changed its mind. Its London directorate was, in fact, angry that its local servants had accepted the invitation from a weak local rajah to build a fort, and even angrier when the rajah failed to honour an undertaking to pay for it.

It was only with the restoration of Charles II in 1660 that the Company entered a phase of sustained growth. Under Charles I it had nearly collapsed; with the Restoration its days of prosperity and grandeur could be said to begin. Yet this is unfair to the Cromwellian regime which in 1657 re-chartered the Company as a united joint stock to which three-quarters of a million pounds were promptly subscribed. The roots of the social conservatism and aggressive commercial imperialism which were so characteristic of Restoration England are to be found in the Cromwellian Protectorate, and of this fact there is no better example than the man who came to dominate the Restoration East India Company - Sir Josiah Child.

Born in London in 1630, the second son of a merchant with East and West Indian interests, Josiah Child rose to prominence as a victualler and deputy naval treasurer to Cromwell's fleet in Portsmouth, where he gained access to the ruling town oligarchy by his marriage in 1654 to Hannah Boate, daughter of a Portsmouth master shipwright. By 1658, Child had become mayor of Portsmouth. The town corporation was puritanical and republican in sympathy, backing Sir Arthur Heselrige and the Rump Parliament in 1659 against the grandees of the Commonwealth army. With the return of Charles II in 1660 the republican oligarchy was soon purged by a visiting commission enforcing the terms of the Corporation Act of 1661. Mayor John Tippets and other prominent figures like Josiah Child were deprived and disenfranchised and, after his wife's death in the same year, Child returned to London.

They both recovered fast. The Restoration regime continued the Cromwellian tradition of maritime and commercial imperialism with an Act of Navigation and predatory wars against the Dutch. Tippets, a master shipwright, was a useful man to Charles II. (Until 1669, when it was taken over by a clique of émigrés whose outlook was scarcely English, that monarch's government was really a coalition of returned Royalists and former Cromwellians.) Tippets became a Commissioner of the Navy in 1668 and was knighted in 1675. Josiah Child needed longer to worm his way into royal favour, but he never lost his knack for making money.

He had been provisioning East India Company ships in Portsmouth as early as 1659, so it was only natural that he should continue to do so after his return to London. Whether he was technically 'free of the Company' (that is to say a member of it) was a matter of some debate amongst the 'committees' or directors in 1664. He was certainly a major bidder for Company provision contracts in the later 1660s. Marriage had helped Child in Portsmouth, and after his remarriage in 1663 to a lady who was both the daughter and the widow of London merchants, Child built a brewery in Southwark. His beer was said to be terrible, but he sold it to the navy, to whom he also sold mast timbers from America. Indeed, he was turning into an all-round commercial imperialist. He was also co-owner of 1,330 acres in Jamaica, and a founder member of the Royal Africa Company, which was sponsored by the Duke of York, heir presumptive to Charles II. As Member of Parliament for Dartmouth from 1673, Child had enough political influence to form a syndicate with Thomas Papillon and Sir Thomas Littleton and force his way into a major share of naval victualling contracts despite the hostility of the Secretary of the Admiralty, Samuel Pepys.

Child bought his way into the East India Company; by December 31st, 1675, he was the biggest investor in the New General Stock, with £12,000 out of the total stock balance of £369,891 divided among 554 adventurers. He had been elected to the Court of Committees (the directorate) in April 1674 and was active as a representative of the Company in the negotiations which concluded the unpopular and unsuccessful Third Dutch War of 1672-74. Partly because of his sustained sniping at Charles It's great minister Danby, whose aggressive Anglicanism did not appeal to the old Cromwellian in Child, Josiah Child was still not acceptable to his sovereign. When Charles heard in April 1676 that the East india Company was on the verge of electing Child and his close associate Thomas Papillon 'Governor and Sub-Governor for the year ensuing', he had Secretary of State, Sir Joseph Williamson, convey his displeasure, saying 'His Majesty should take it very ill of the Company if they should chuse them'.

It was too late to stop Child's election to the directorate, but the royal veto on his leadership was accepted until Child made his peace with the Crown, which he did in two ways. He did not join in the attack on the Roman Catholic Duke of York's right to succeed his brother during the Exclusion Crisis. For that he was rewarded with a baronetcy. In 1679 he had been given general oversight of the affairs of 'the coast and the bay' (Madras and Bengal in modern parlance), and 1682 saw Sir Josiah persuade the General Court of stockholders that it was 'consistent with the Company's duty and interest to make a present to His Majesty of 10,000 guineas'. A smaller payment went to York, and the royal brothers came )o rely on their annual Christmas presents from the East India Company. Child duly became Deputy Governor in 1684 and Governor in 1686.

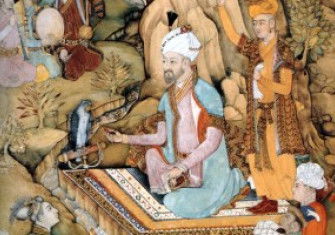

Circumstances were changing in India, too. The Moghul Empire never really recovered from the wars of succession in 1657-60 between the sons of the Emperor Shahjahan, and though the victor, the Emperor Aurangzeb, proved a great ruler, he failed to check, indeed did much to provoke, the militant Hindu revivalism of the Maratha people. Led by the great warrior-king Sivaji, who died in 1680, Maratha armies rampaged along the Malabar Coast, raiding Surat, the principal East India Company trading port in India, in 1664 and 1667. Sir George Oxenden, President of the East India Company Council in Surat, helped the Moghul Governor fend off the 1664 assault. Oxenden had only a handful of Europeans and a few mercenaries to guard his warehouses, but Aurangzeb noticed and honoured his valour.

The European garrison at Fort St George on the Coromandel Coast had by 1655 fallen as low as twenty-five men, so nobody could accuse the English of plans of conquest. They did acquire Bombay in 1661 as part of the dowry for Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese bride of Charles II, but the King regarded this island base as an expensive pest, so he wished it on the East India Company in 1668 for an annual rent of £10. In December 1667 his royal garrison there had numbered ninty-three English, forty-two Portuguese and French, and 150 men recruited from the great south India plateau of the Deccan.

The directors of the East India Company were still in 1681 emphatic that 'all war is... contrary to our constitution as well as our interest'. Geral Aungier, who between 1669 and 1677 governed Bombay with great ability for them, did not argue with the principle, but he was clear that:

The state of India is much altered to what it was; that justice and respect, wherewith strangers were wont to be treated with, is quite laid aside,... The times now require you to manage your general commerce with your sword in your hands.

Sir Josiah tied the East India Company to the chariot of late Stuart imperialism, and that imperialism was extremely assertive.

In India Sir Josiah's protege John Child (who was not a relative, despite his name) had been rapidly rising in the East India Company hierarchy at Surat. From the lucrative post of factor he moved into the council which advised the Company President at Surat, and in 1680 he became Deputy-Governor of Bombay. The directorate still operated on the assumption that the East India Company was a purely private body whose job was to cut costs and make profits for stockholders, so they pressed for reductions in military pay and allowances. John Child tried to enforce these cuts on an already discontented Bombay garrison, provoking a rebellion led by Captain Richard Keigwin, the dashing commander of a miniscule force of cavalry raised to repel hit-and-run raids on the few square miles of English territory. In 1683 Keigwin arrested Ward, the resident Governor of Bombay, and repudiated Company authority, claiming to rule directly on behalf of Charles II.

The monarch was, however, much more open to suggestions from Sir Josiah Child than from Keigwin. Charles was persuaded to issue a commission under the Great Seal making John Child, now Sir John, Captain General and Admiral of all East India Company forces, with Sir Thomas Grantham, as his Vice-Admiral. Grantham had had experience of such affairs - having been sent to Virginia in 1676 to suppress a local rebellion. After the arrival of a flotilla of ten ships led by Grantham's HMS Phoenix in November 1684, Keigwin prudently surrendered and Sir John was annoyed to find that in exchange 'that notorious naughty rascal' was to be pardoned for his rebellion. Charles II could use his talents. Keigwin was to die gallantly in action fighting for the Crown. However, Charles did insist that the Company keep a minimum of three infantry companies at Bombay in future, and move its headquarters from Surat to Bombay since 'we are positively resolved never to be enslaved by the Moor's Government hereafter'. It was an indirect but real challenge to Moghul authority by a Company which now had in India precisely the sort of incipient sub-imperialism which it used to be thought only emerged in the mid-eighteenth century. Assertive Company magnates in London, like Sir Josiah, had intimate links with aggressive Company officers in India, like Sir John, and the latter had access to royal naval and military power. That still did not make Sir John a trained soldier. Robert Clive was not a trained professional, but he proved in the 1750s to be a natural soldier. Sir John had neither training nor talent. As a contemporary said:

He was a General but no soldier; and better skilled at his pen than his sword; and more expert in casting an account than in martialling [sic] and conducting an army.

Yet as Sir Josiah progressed to Deputy Governor of the East India Company in 1684 and Governor in 1686, he embarked with Sir John and their mutual patron the Duke of York Qames VII and II from 1685) on a policy which was bound to lead to armed conflict in India. Restoration England conducted much of its foreign business with an arrogant style and a militarised personnel. Thus the Earl of Carlisle, a soldier-bureaucrat who learned his trade under Cromwell, had been sent by Charles II to demand exemption from customs dues for English merchants in Russia, and when the Tsar declined on the reasonable grounds that he needed the money, Charles II toyed briefly with the idea of attacking Russia in alliance with Sweden. Any payments to the Moghul Empire were, of course, liable in this atmosphere to be seen as 'unreasonable'. Some exactions by Moghul officials no doubt were excessive, but all and every payment was resented.

Thereafter the directorate of the East India Company took a conscious decision to concentrate its activities in India in a series of heavily-fortified port centres over which it would exercise absolute authority. Innocent as this preference for fortified entrepots might look at first sight, it threatened the sovereignty of any local ruler in two ways. First, it involved flouting any authority not prepared to grant permission to fortify. Secondly, it threatened the large customs component in a maritime region's state income. The shift of emphasis from Surat to Bombay was a shift from a Moghul city to an (inadequately) fortified English sovereign enclave. Madras was already fortified. The flashpoint was therefore bound to be the great and rich province of Bengal, which was emerging as the most lucrative area for European commerce in India, mainly because of the abundance and low prices of its principal export goods. The East India Company had several trading posts in the Ganges delta including factories (secure warehouse-complexes) at Kazimbazar, Patna and Hugli. The Council of the Bay, which ruled them, was in 1686 presided over by the formidable Job Charnock who was already on bad terms with the Moghul viceregal administration in India over disputed debt, cases involving local merchants, and Charnock's physical resistance to the officers of the foujdar or criminal magistrate of Hugli, who tried to distrain his assets. By April 1686 Charnock, using troops which had been unexpectedly sent out by the court of directors, trounced the police forces of the foujdar.

The very able Moghul Viceroy of Bengal, Shaista Khan, had made his name by dealing with one set of European ruffians. These were slavers and pirates from the so-called 'shadow empire' of Portugal on the Coroman-del Coast: men of mixed blood who acknowledged the Archbishop of Goa, but not the Portuguese Viceroy there. Operating from a base in the Ganges delta, their slaving galleys had terrorised the peasantry until the Viceroy built forts on the Ganges and overwhelmed their ill-defended township by sheer weight of numbers. Some Portuguese renegades continued their activities from refuge in the Buddhist kingdom of Arakan, whose ruler had pretensions to the conquest of Bengal. Indeed the English in 1686-87 offered assistance against the Arakanese to Shaista Khan as an incentive to accept their demands.

There were in the end four points of conflict. One was the old East India Company centre of Surat where relations with the Moghul governor deteriorated when he tried to raise dues on British trade from 2\ per cent to a more realistic four. That conflict eventually bred violence at Bombay. Simultaneously, the East India Company managed to become involved in a naval war in the Bay of Bengal with the Kingdom of Siarn, whose Greek foreign minister, one Phaulkion, was accused of intriguing with Louis XIV of France and of opening Siamese ports like Mergui to renegades from Company service who then violated its trade monopoly. Certainly, one of these men, Samuel White, known as 'Siamese White', was governor of Mergui. In 1688 the East India Company sent two frigates to attack Mergui, and a war of attacks on trading vessels spluttered and flared until the fall of Phaulkion in 1688.

By this time war in Bengal had been going on for some while. After William Hedges, the Company's special envoy to the Viceroy, had failed to secure satisfaction, Job Charnock demanded 'a place or Town by Salt Water for the building of a strong or fortified Factory' where he could 'Negotiate free of all duties'. Char-nock's hand had been strengthened by the despatch of a flotilla of ten ships from England, carrying six companies of infantry to reinforce the few hundred European and mixed-blood troops which the Company kept to police rather than defend its Bengal establishments. The flotilla had a royal commission from James VII and II, but this hardly compensated for the loss of three ships on the way out, or the lack of any officers above the rank of lieutenant. Char-nock and the merchants of his council were to assume the senior commands, despite their lack of professional training. They were able to expel the Moghul forces from Hugli in October 1686 by means of a surprise assault backed by a naval bombardment, but then they made the fatal mistake of negotiating with local Moghul officials. They would have been wiser to implement the orders which the directorate of the East India Company had sent out with the flotilla. These envisaged the seizure and fortification of Chittagong, a port on the east coast of Bengal. It is true that the second phase of operations envisaged by the orders - an attack on the regional capital of Dacca - would certainly have proven counter-productive, but no more so than staying in Hugli, a town well within reach of the army of the Viceroy of Bengal, and on a river which enabled him easily to concentrate troops and supplies.

The army of the Viceroy (whose Indian title was Nawab) was still built round a cavalry force. It had plenty of irregular infantry, many of them matchlock men, and could deploy a ponderous seige-train of very heavy cannon, but its essence lay in its sabre-wielding troopers. Charnock's forces could not generate enough fire-power to stop their charge. They lacked adequate mobile field artillery like the quick-firing six-pounders whose grapeshot were to serve Clive so well. Above all, the English soldiers of 1686-88 needed a fair proportion of their ranks (a minimum of a third) to wield pikes to protect the musketeers from cavalry whilst they went through the slow process of reloading their matchlock muskets which used a smouldering cord to fire the propel-lant. Effective bayonets were not really available until the 1690s. Driven from Hugli, Charnock retreated, destroying Moghul river forts, granaries and salt stores on his way. He was chased from his refuge at Sutanati, near a convenient deep anchorage, and ended up on the insalubrious island of Hijli where he repulsed an attack, but lost most of his surviving men to fever. He wisely started to negotiate a compromise settlement, aided by the effectiveness of his naval blockade, which was depriving the Nawab of customs revenue, when the arrival of Captain Heath from England with a sixty-four-gun man o' war, a frigate, and 160 soldiers wrecked hopes of compromise. Heath bombarded the town of Balasore, wisely jibbed at attacking a well-defended Chittagong, and then evacuated all English to Madras, where the council was busy urging its London masters to stop fighting two pointless wars.

For the Emperor Aurangzeb, Balasore was the last straw. Busy campaigning in the Deccan, he had treated the antics of the East India Company as an irrelevance, but Sir John Child's interference with the pilgrim traffic from Surat to Mecca vexed the pious emperor, and Captain Heath's behaviour enraged him. Sir John had retreated from Surat to Bombay in 1687. By 1638 the Moghul authorities had arrested English goods and merchants in Surat, while Sir John boasted that if their admiral attacked Bombay he would 'blow him off again with the wind of his Bum'. Alas, when the Moghul admiral Sidi Yakub Khan did land on Bombay with 20,000 men, Sir John was rapidly chased into Bombay Castle, which was inadequately fortified due to his previous ill-judged economies, and commanded by a hill on which the Sidi mounted a battery which pounded Bombay Castle with huge stone cannon balls or tossed mortar bombs (made from hollowed-out stones) over its parapets. There was no alternative to abject capitulation to the Emperor Aurangzeb, who might then call off the siege. It had not been particularly bloody. Casualties on the East India Company side were 104 killed, 130 wounded and 116 'run away', but the Company was in deep political trouble back home where the Glorious Revolution of 1688 had ousted its patron James II, and given those parliamentarians who had always detested its monopoly of English trade in the East a chance to win the ear of the new monarch, William III. In a shrewd career move, Sir John Child died and retired to a splendid tomb before the final peace terms, which involved his permanent exclusion from India, were put into force.

A contemptuous Imperial Firman or decree of the Emperor Aurangzeb in February 1690 readmitted the East India Company to trade in his dominions as before the war in exchange for a grovelling admission of guilt and a stiff fine of 150,000 rupees (at the time about £15,000). To Aurangzeb the Company was still a mere flea on the back of his imperial elephant. The Company was chastened. News of the decree's terms sharpened the crisis it faced in London, a crisis culminating in 1698 in Parliament chartering a General Society designed to supersede it. It may be argued that the Childs and James II never aimed at direct rule in Bengal, but then neither did Clive in 1757. What was at stake both times was military and commercial ascendancy. There is no reason to believe that victory for the Childs would have had results any different from those which followed Clive's triumph: subversion of indigenous institutions leading to direct rule. What changed between 1686 and 1757 was English military capacity, and the cohesion of the Moghul Empire.

For Further Reading:

James P. Lawford, Britain's Army in India from its Origins to the Conquest of Bengal (Alien & Unwin, 1978); David Chandler, The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough (B.T. Batsford Ltd., London 1976); K.N. Chaudhuri, The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company 1660-1760 (Cambridge University Press, 1978); Vincent A. Smith, The Oxford History of India, 3rd edn, ed Percival Spear (Oxford University Press, 1958); Perciva] Spear, Penguin History of India, Vol II; Arnold Wright, Annesley of Surat (London, 1918); W. Irvine, The Army of the Indian Moghuls: Us Organisation and Administration (London, 1903).

Bruce Lenman is reader in modern history at the University of St Andrews and author of The Jacobite Cause (Richard Drew).