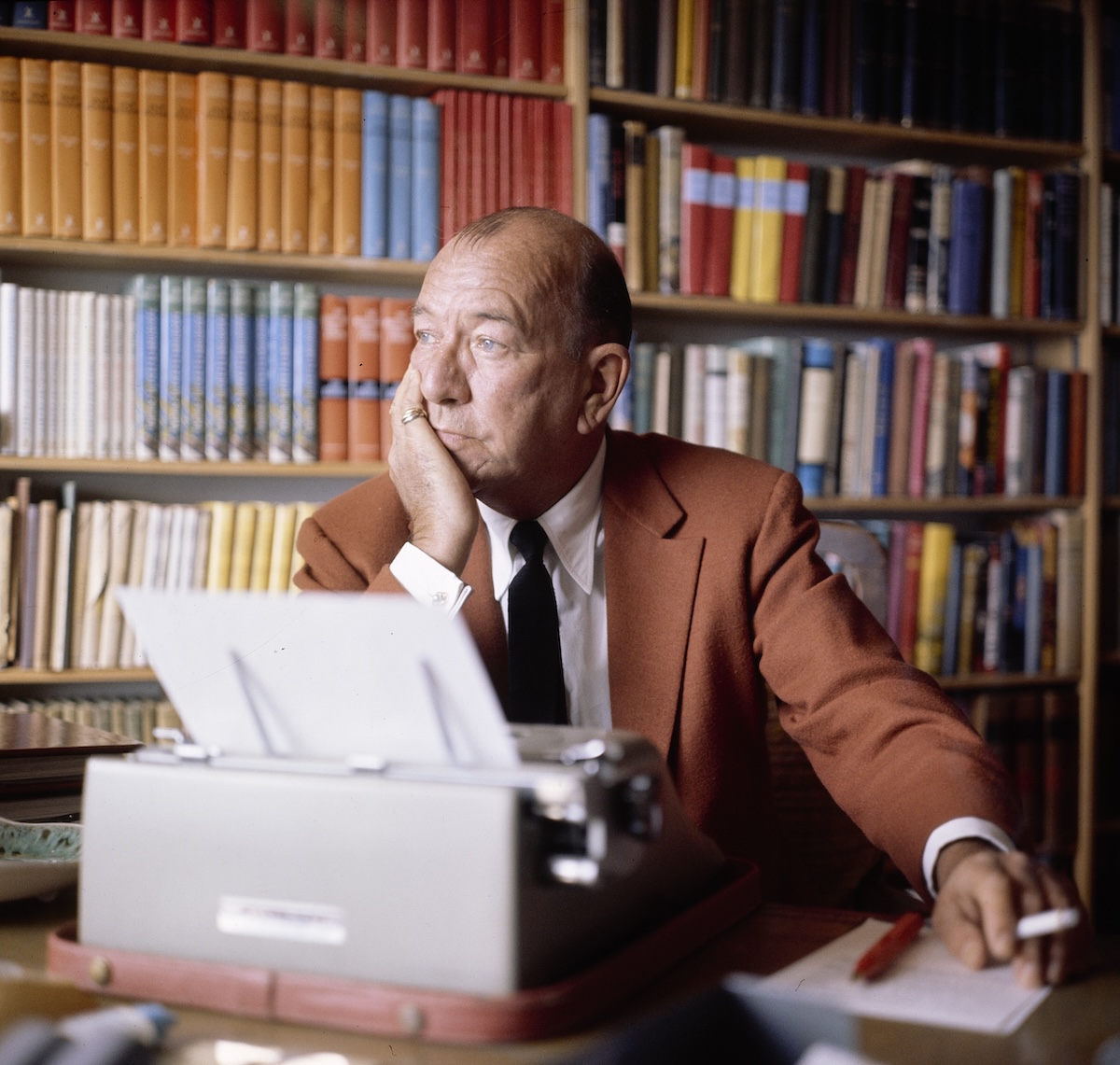

Noël Coward and the Second World War

Told by Churchill to ‘go and sing when the guns are firing’, Noël Coward aspired to do more during the Second World War than entertain the troops.

It was as a writer and performer that Noël Coward (1899-1973) is best remembered for his war effort, most obviously in the form of his much-lauded propaganda film In Which We Serve (1942). Yet this notable achievement masks a series of personal disappointments for Coward, who thought he had much more to offer than his talents as an entertainer. In fact he had a varied wartime career, characterised by commitment, energy and generosity on several levels.