Chamberlain, Appeasement, and the Wait for War

The wait for the outcome of Neville Chamberlain’s mission to Munich and the looming spectre of another war hung over Britain in 1938. Its impact was deeply felt.

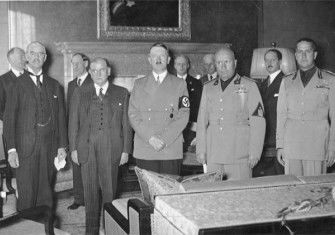

After the annexation of Austria in March 1938, Hitler set his sights on the Sudetenland. This part of the newly formed Czechoslovakia had a majority German-speaking population. Hitler’s territorial ambitions threatened to propel Europe into another world war. Both the democracies and the dictatorships, as well as their respective populations, were materially and psychologically unprepared and ill-equipped for another total war. It was feared that this would be a war in which ‘the bomber will always get through’, making little distinction between civilian and soldier. The British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain personified both the policy and the sensibility of appeasement, ready to make concessions to Germany to avoid war. In an act of personally courageous statesmanship, in the eyes of many, Chamberlain paid three visits to Hitler in a span of two weeks, the third on 29-30 September for the Four Powers Conference (Germany, Britain, Italy and France), where the Munich Agreement and the fate of Czechoslovakia was sealed.