Khans of Crimea

The Crimean Khanate was the last surviving heir of Chinggis Khan’s dynasty. Respected, feared and reviled, it found itself caught between the Russian and Ottoman empires.

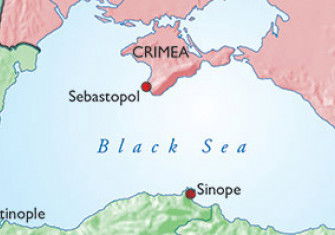

When Norman Davies published Vanished Kingdoms: The History of Half-Forgotten Europe in 2011 he remembered Alt Clud and Aragon, but forgot the Crimean Khanate. Perhaps he considered the Crimean Khanate a mere vassal of the Ottoman Empire. That would be a mistake: the Khanate had its own laws; its khans were all from the Giray family, descended from Chinggis Khan; and between the 15th and 18th centuries it often acted independently of the Ottomans, in both diplomacy and war. The Crimean peninsula, approached by land through a narrow isthmus, with a rocky coast, has been a refuge for imperilled nations since the first millennium: defeated Huns, Ostrogoths, Khazars, Jews, Armenians, Greek and Italian traders, dominated by the Qipchaq Turks, created, in a land barely larger than Wales, the world’s most diverse and viable ethnic mix. With rich human and natural resources, perfectly positioned for trade between Europe and Asia, the Crimean Khanate shaped central and eastern Europe for 300 years. Now it is gone and the Crimean Tatars are a minority in their own land.